Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (22 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

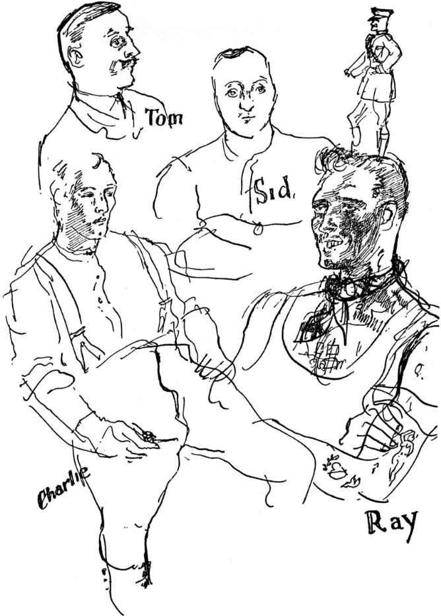

Our family was large, even by the full-bred standards of those days, and we were especially well-endowed with uncles. Not so much by their numbers as by their qualities of behaviour, which transformed them for us boys into figures of legend, and filled the girls with distress and excitement. Uncle George – our father’s brother – was a thin, whiskered rogue, who sold newspapers in the streets, lived for the most part in rags, and was said to have a fortune in gold. But on my Mother’s side there were these five more uncles: squat, hard-hitting, heavy-drinking heroes whom we loved and who were the kings of our youth. For the affection we bore them and the pride we took in them, I hope they’ll not be displeased by what follows.

Grandfather Light – who had the handsomest legs of any coachman in Gloucestershire – raised his five sons in a world of horses; and they inherited much of his skill. Two of them fought against the Boers; and all five were cavalrymen in the First World War, where they survived the massacres of Mons and Ypres, quickwitted their way through some others, and returned at last to peace and salvation with shrapnel in each of their bodies. I remember them first as khaki ghosts coming home on leave from the fighting, square and huge with their legs in puttees, smelling sweetly of leather and oats. They appeared as warriors stained with battle; they slept like the dead all day; then blackened their boots and Brassoed their buttons and returned again to the war. They were men of great strength, of bloody deeds, a fist of uncles aimed at the foe, riders of hell and apocalypse, each one half-man, half-horse.

Not until after the war did that brotherhood of avengers detach itself in my mind, so that I was able to see each one separate and human and to know at last who they were. The sons of John Light, the five Light brothers, illuminated many a local myth, were admired for their wildness, their force of arms, and for their leisurely, boasting wit. ‘We come from the oldest family in the world. We’re down in the Book of Genesis. The Almighty said, ‘Let there be Light’ – and

that

was long afore Adam…’

The uncles were all of them bred as coachmen and intended to follow their father; but the Army released them to a different world, and by the time I was old enough to register what they were up to only one worked with horses, the others followed separate careers; one with trees, one with motors, another with ships, and the last building Canadian railways.

Uncle Charlie, the eldest, was most like my grandfather. He had the same long face and shapely gaitered legs, the same tobacco-kippered smell about him, the same slow story-telling voice heavy with Gloucester bass-notes. He told us long tales of war and endurance, of taming horses in Flanders mud, of tricks of survival in the battlefield which scorned conventional heroism. He recounted these histories with stone-faced humour, with a cool self-knowing wryness, so that the surmounting of each of his life-and-death dilemmas sounded no more than a slick win at cards.

Now that he had returned at last from his mysterious wars he had taken up work as a forester, living in the depths of various local woods with a wife and four beautiful children. As he moved around, each cottage he settled in took on the same woody stamp of his calling, putting me in mind of charcoal-burners and the lost forest-huts of Grimm. We boys loved to visit the Uncle Charles family, to track them down in the forest. The house would be wrapped in aromatic smoke, with winter logs piled in the yard, while from eaves and door-posts hung stoats’-tails, fox-skins, crow-bones, gin-traps, and mice. In the kitchen there were axes and guns on the walls, a stone-jar of ginger in the corner, and on the mountainous fire a bubbling stew-pot of pigeon or perhaps a new-skinned hare.

There was some curious riddle about Uncle Charlie’s early life which not even our Mother could explain. When the Boer War ended he had worked for a time in a diamond town as a barman. Those were wide open days when a barman’s duties included an ability to knock drunks cold. Uncle Charlie was obviously suited to this, for he was a lion of a man in his youth. The miners would descend from their sweating camps, pockets heavy with diamond dust, buy up barrels of whisky, drink themselves crazy, then start to burn down the saloon… This was where Uncle Charles came in, the king-fish of those swilling bars, whose muscled bottle-swinging arm would then lay them out in rows. But even he was no superman and suffered his share of damage. The men used him one night as a battering-ram to break open a liquor store. He lay for two days with a broken skull, and still had a fine bump to prove it.

Then for two or three years he disappeared completely and went underground in the Johannesburg stews. No letters or news were received during that time, and what happened was never explained. Then suddenly, without warning, he turned up in Stroud, pale and thin and penniless. He wouldn’t say where he’d been, or discuss what he’d done, but he’d finished his wanderings, he said. So a girl from our district, handsome Fanny Causon, took him and married him.

He settled then in the local forests and became one of the best woodsmen in the Cotswolds. His employers flattered, cherished, and underpaid him; but he was content among his trees. He raised his family on labourer’s pay, fed them on game from the woods, gave his daughters no discipline other than his humour, and taught his sons the skill of his heart.

It was a revelation of mystery to see him at work, somewhere in a cleared spread of the woods, handling seedlings like new-hatched birds, shaking out delicately their fibrous claws, and setting them firmly along the banks and hollows in the nests that his fingers had made. His gestures were caressive yet instinctive with power, and the plants settled ravenously to his touch, seemed to spread their small leaves with immediate life and to become rooted for ever where he left them.

The new woods rising in Horsley now, in Sheepscombe, in Rendcombe and Colne, are the forests my Uncle Charlie planted on thirty-five shillings a week. His are those mansions of summer shade, lifting skylines of leaves and birds, those blocks of new green now climbing our hills to restore their remembered perspectives. He died last year, and so did his wife – they died within a week of each other. But Uncle Charlie has left a mark on our landscape as permanent as he could wish.

The next of the Lights was Uncle Tom, a dark, quiet talker, full of hidden strength, who possessed a way with women. As I first remember him he was coachman-gardener at an old house in Woodchester. He was married by then to my Aunty Minnie – a tiny, pretty, parted-down-the-middle woman who resembled a Cruickshank drawing. Life in their small, neat stable-yard – surrounded by potted ferns, high-stepping ponies, and bright-painted traps and carriages – always seemed to me more toylike than human, and to visit them was to change one’s scale and to leave the ponderous world behind.

Uncle Tom was well-mannered, something of a dandy, and he did peculiar things with his eyebrows. He could slide them independently up and down his forehead, and the habit was strangely suggestive. In moments of silence he did it constantly, as though to assure us he wished us well; and to this trick was ascribed much of his success with women – to this and to his dignified presence. As a bachelor he had suffered almost continuous pursuit; but though slow in manner he was fleet of foot and had given the girls a long run. Our Mother was proud of his successes. ‘He was a cut above the usual,’ she’d say. ‘A proper gentleman. Just like King Edward. He thought nothing of spending a pound.’

When he was young, the girls died for him daily and bribed our Mother to plead their cause. They were always inviting her out to tea and things, and sending him messages, and ardent letters, wrapped up in bright scarves for herself. ‘I was the most popular girl in the district,’ she said. ‘Our Tom was so refined…’

For years Uncle Tom played a wily game and avoided entanglements. Then he met his match in Effie Mansell, a girl as ruthless as she was plain. According to Mother, Effie M was a monster, six foot high and as strong as a farm horse. No sooner had she decided that she wanted Uncle Tom than she knocked him off his bicycle and told him. The very next morning he ran away to Worcester and took a job as a tram-conductor. He would have done far better to have gone down the mines, for the girl followed hot on his heels. She began to ride up and down all day long on his tram, where she had him at her mercy; and what made it worse, he had to pay her fares: he had never been so humiliated. In the end his nerve broke, he muddled the change, got the sack, and went to hide in a brick-quarry. But the danger passed, Effie married an inspector, and Uncle Tom returned to his horses.

By now he was chastened, and the stables reassured him – you could escape on a horse, not a tram. But what he wished for more than anything was a good woman’s protection: he had found the pace too hot. So very soon after, he married the Minnie of his choice, abandoned his bachelor successes, and settled for good with a sigh of relief and a few astonishing runs on his eyebrows.

From then on Uncle Tom lived quietly and gratefully like a prince in deliberate exile, merely dressing his face, from time to time, in those mantles of majesty and charm, those solemn winks and knowing convulsions of the brow which were all that remained of past grandeur…

My first encounter with Uncle Ray – prospector, dynamiter, buffalo-fighter, and builder of transcontinental railways – was an occasion of memorable suddenness. One moment he was a legend at the other end of the world, the next he was in my bed. Accustomed only to the satiny bodies of my younger brothers and sisters, I awoke one morning to find snoring beside me a huge and scaly man. I touched the thick legs and knotted arms and pondered the barbs of his chin, felt the crocodile flesh of this magnificent creature, and wondered what it could be.

‘It’s your Uncle Ray come home,’ whispered Mother. ‘Get up now and let him sleep.’

I saw the rust-brown face, a gaunt Indian nose, and smelt a reek of cigars and train-oil. Here was the hero of our school-boasting days, and to look on him was no disappointment. He was shiny as iron, worn as a rock, and lay like a chieftain sleeping. He’d come home on a visit from building his railways, loaded with money and thirst, and the days he spent at our house that time were full of wonder and conflagration.

For one thing he was unlike any other man we’d ever seen – or heard of, if it comes to that. With his leather-beaten face, wide teeth-crammed mouth, and far-seeing ice-blue eyes, he looked like some wigwam warrior stained with suns and heroic slaughter. He spoke the Canadian dialect of the railway camps in a drawl through his resonant nose. His body was tattooed in every quarter – ships in full sail, flags of all nations, reptiles, and round-eyed maidens. By cunning flexing of his muscles he could sail these ships, wave the flags in the wind, and coil snakes round the quivering girls.

Uncle Ray was a gift of the devil to us, a monstrous toy, a good-natured freak, more exotic than a circus ape. He would sit quite still while we examined him and absorb all our punishment. If we hit him he howled, if we pinched him he sobbed: he bore our aches and cramps like a Caliban. Or at a word he’d swing us round by our feet, or stand us upon his stomach, or lift us in pairs, one on either hand, and bump our heads on the ceiling.

But sooner or later he always said:

‘Waal, boys, I gotta be going.’

He’d stand up and shake us off like fleas and start slowly to lick his lips.

‘Where you got to go to, Uncle?’

‘See a man ‘bout a mule.’

‘You ain’t! Where you going! What for?’

‘Get my fingers pressed. Tongue starched. Back oiled.’