Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (68 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

Here were young veterans and half-trained newcomers, combatants but a short bus-ride from the front, those who had slipped past death and returned, and those who must very soon die; a few officers, agents, spies, touts and journalists – all who found in this cellar in this huge dark city an incongruous moment of temporary comfort.

After supper Captain Sam called me up to his room, where I found two dramatically dissimilar persons crouched over a table nodding and chanting in broken English. One was bald and round as a Michelin tyre man, the other slim and pretty as a schoolgirl.Spread before them on the table were two half-eaten tomatoes, some crumbling dried fish, and an English translation of Machado, which both were intoning.

Sam introduced us: the round man, Esterhazy, an Austrian writer; the pretty youth, Ignacio, ex-student of English and Arabic at the University of Salamanca.

‘Tell us the accent!’ cried Esterhazy, waving to me. ‘Come along, comrade, instruct us, please!’

Sam said my accent was terrible, even he couldn’t understand it. Nevertheless, we rehearsed the poem, which they were going to broadcast together that night, in chorus, and taking alternate verses.

Ignacio was most rousing, even feminine, speaking as it were below the waist, his voice slender, flesh-warm and caressing, his eyes changing shadow with every line. Billowing Esterhazy, meanwhile, provided the windy brass-section, grunting and blaring beneath the other’s treble.

In the end, they built up a fine duet between them, swaying together at the littered table, while Sam and I worked out the rest of the programme which was made up of chatty interviews, propaganda and ‘culture’.

Our first short-wave broadcast was timed for midnight, and theoretically beamed to East Coast America. It was planned as a beleaguered, backs-to-the-wall, defiant call for help; and some of those things it certainly turned out to be.

A couple of armed militiamen picked us up about eleven, their job to guide us through the streets to the radio station. We’d drunk several bottles of wine by then and considered ourselves well rehearsed, and we swaggered out through the dim-lit hall. The streets were almost deserted – no traffic, a distant cry, a few late footfalls of the night, the wind from the Sierras lightly ruffling the shutters.

Sam told us to stick close to the militiamen and, if challenged, to freeze. We moved by the faint glimmer of oil-lamps shining under the curtains of doorways, by the thin glow of starlight on the edge of the rooftops. The air was as cold as mile-high Madrid could be. Sam shivered and swore. Esterhazy blew self-comforting bubbles in his cheeks. The militiamen coughed and spat. From the next street came a shout and the sound of running feet. Young Ignacio gripped my arm.

‘I am a poet,’ I remember him saying. ‘I don’t wish to be here. I belong to music and song, not war.’

We had left the city centre and were stumbling down side-streets, when one of the militiamen tripped up and cursed. A shadowy bundle lay on the pavement, a bundle that gave a weak, old cry. The soldier lit a match. ‘You can’t sleep here, grandmother. If you try to sleep here, you’ll die.’

We knocked at a nearby door, and roused a trembling couple, who lit a candle while we carried the old soul inside.

The wife recognized her with a cry, and said she used to run a kiosk in the square; it was her home, but it had just recently been destroyed by a shell.

‘They fall at all times, as you know. Both night and day. We are none of us safe, before God.’ Distraught and whining, she clutched at her throat and threw a helpless glance at her husband.

‘Dead by our door. The shame of it! How shall we face the world?’

The husband told her not to be stupid, and said he would fetch a hand-cart in the morning and wheel the old woman to hospital. He peered at us nervously, then raised his hand. ‘Go with God,’ he said. ‘And long live the Republic!’

Now it was late, and we hurried on to the next road-block, which was under a railway bridge. It was heavily armed, but no one knew the password, not even our guides, or Sam. We saw the gleam of teeth, the glitter of bayonets, and heard the jaunty cocking of rifles. Then suddenly one of the sentries cried, ‘Aren’t you Rocio?’ and one of our soldiers said, ‘Yes.’ They were fishermen from the same village, were brought up together, but, judging from their conversation, didn’t like each other much. But they let us through, stumbling over tins and stones, accompanied by jolly in-bred insults.

The broadcasting studio was in a dank dark basement in a Victorian-style tenement. As we stumbled down the stairs, stepping over heaps of refuse, the building throbbed and snored with sleepers of all ages, most of the rooms having been set aside for soldiers’ families.

Sam led us to a cramped little room stuffed with coils and valves, where a young blond announcer, sweating in his shirtsleeves, read a war communique in Teutonic English. He winked at Sam as we entered and nodded towards a table, around which we grouped ourselves. Finally, from this tiny cell in Madrid, fumed by wine and tobacco smoke, we went into our broadcast – three thousand miles across the winter seas. Who could be listening, I wondered – truck-drivers sealed in their cabs, young radio hams skimming the air-waves, bored barmen and husbands seeking the evening sports news, widows in Long Island mansions awaiting their lovers?

I doubt that they could, or would, or did. Sam took the mike and read out the manifesto we had stitched up together, ending with a list of names of some Lincoln Brigade heroes. As a climax we had planned to play a few bars of the ‘Internationale’, but we mixed up the labels and put on ‘The Skater’s Waltz’ instead. But I had a feeling that we could not be heard at all, that the microphones were simply not connected to anything, that this was all a pantomime to placate the gods.

Nevertheless, we kept on with it. Esterhazy and Ignacio took their turn, and droned and fluted into their prepared Machado. I don’t know what the effect of an obscure Spanish poem, in a bad English translation, delivered in unison by a booming Austrian and a nervous young Madrilefio, would have on an uncertain audience thousands of miles away, but one doubted that it would command their single-minded attention or cause them much stirring of the breast.

Not that Sam’s and my contribution was any more compelling.

We had worked out an interview in which Sam questioned me about the volunteer routes across the Pyrenees. This had seemed easy and matter of fact enough when we rehearsed it earlier that evening, but once returned to the microphone, in this more casual role, Sam’s personality suffered a cardinal breakdown – gone was the urbane propagandist, the donnish debater, the merciless interrogator of spies and traitors, the ice-cold political killer – suddenly I was confronted with an oily and unctuous crawler, and this fawning Sam was an unsettling experience.

The unreality disappeared when the shelling began, somewhere about three in the morning. We heard it first as a distant metallic bark, honed and polished by the freezing air, followed by an indrawn silence, a rapidly approaching whine, then the brief uproar of exploding masonry. Curiously, these sounds then seemed to fall back on themselves, receding in waves of silence, shouts, running feet, and finally in distant cries.

The first shell broke some glass, shook the studio walls, juggled the furniture, and brought down some dust. The engineer signalled to us to go on, and this we did, and at last the broadcast seemed to make some sense. We began to talk together in normal voices, to ask each other why we were here. Captain Sam’s face returned to its original protean calm. His back straightened and he reclaimed his authority. With several minute intervals, both near and far, the shells continued to fall. The studio door opened and a group of women came in, carrying bundles of sleeping or whimpering children. Each of the women’s faces had that pallor of patience and hunger as though they had been rubbed in damp grey ashes. They bowed to us apologetically, hesitated a moment, then sank in a circle around the walls. If we have to die, let us die where there is light, among each other, and near the power of these men talking a kind of Latin, like priests.

So in this cramped semi-basement in the beleaguered city, surrounded by our cloaked, fugitive audience, and to its background of shuffles, sighs and murmurs, and the occasional spiked thud of explosions outside, we talked on, read poems, swinging the microphone between us, while the large frightened eyes of the women stared up at our mouths as if we were conjuring for them, in our foreign tongues, magic spells, incantations and prayers.

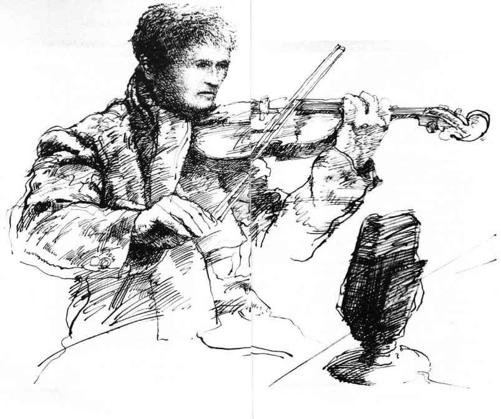

Some time later the German announcer suddenly handed me a battered violin, with an old bow like an unravelled horsewhip. At the sight of the instrument faces softened, eyes brightened, sleeping children were awoken with pinches. ‘Musical… musical’ the whisper went round. And I saw again those expressions of gentle pleasure and anticipation that I’d known in poor Spanish villages before the war.

I didn’t play much, the strings were frayed and greasy, but I scratched away at some old Spanish dances which I’d learned on my previous visit, and I played them as loud and as fast as I could. An intense experience – to the smell of cold and cordite, and with the passing of shells overhead, the veiled women nodding and bowing, and the Madrid night we shared together – intense and not to be forgotten. When I’d finished, Captain Sam announced that a British volunteer had just given a violin recital. We both knew it wasn’t that. The women on the floor gazed at me with benign indulgence, as though watching a neighbour’s child just beginning to walk.

Around about dawn the shelling stopped and the restless children slept. But the families continued to sit round in clumps, forged like clinkers, black and immobile. I slipped out into the street, stepping over pieces of timber and piles of broken brick. In the building next door a great hole had appeared through which one could see the pale morning stars behind. A shell seemed to have passed right through one of the downstairs apartments and cleared out all the furniture except for the carpets. Nothing was left save for one mumbling old woman who sat stiffly upright in the middle of the room.

The stretcher-bearers arrived as I was passing. They took the woman’s arm, but she snatched it away. Her thin grey legs stuck out in front of her, her mouth was twisted with shock. Her family had suddenly disappeared with the furniture, she said. She kept going through their names like a litany. ‘Mi marido, Jacinta, Puelo, Ramon…’ There must have been a dozen or more of them at least. They had been carried away as by some mighty wind, she said. She shook off her rescuers and would not move.

The streets around were blocked with debris. Carts and wagons were clearing up. Oddly enough, there had been no fire, only destruction. A few bodies lay under blankets along the pavements. Here and there somebody hobbled away. There were no shouts, no raised voices, just subdued, desultory, matter-of-fact exchanges as of neighbours starting another day.

The experience of being in Madrid again, contrasting its present cold desolation with the easy days of my earlier visit, made me want to search out some of the places I’d known.

I found the Puerta del Sol smothered in a pall of greyness, and I remembered the one-time buzz of the cafes, the tram bells, the cries of the lottery-ticket sellers, the high-stepping servant girls with their baskets of fresh-scrubbed vegetables, the parading young men and paunchy police at street corners.

Now there was emptiness and silence – the cafes closed, a few huddled women queuing at a shuttered shop. Poor as it had been when I’d known it, there had always been some sense of holiday in the town, a defiant zest for small treats and pleasures, corner stalls selling popcorn, carobs, sunflower seeds, vile cigarettes, and little paper packets of bitter sweets. Nothing now, of course, no smell of bread, oil, or the reek of burnt fish that used to enliven the alleys round the city centre – just a fusty aroma of horses, straw, broken drains and fevered sickness.

I’d previously stayed at an old inn near the Calle Echegarry, where I’d rented a room for sixpence a night and had been looked after by Concha, a young widow from Aranjuez. Carters from the Sierras slept with their beasts in the stables, and the landlord kept a cow in the cellar.

I found the place transfigured. The great twenty-foot doors, which for some five hundred years had hung or swung on their elaborate tree-sized hinges, had now, after withstanding generations of war and plague, been torn down and burned as fuel. The cobbled courtyard within, once crowded with mules and wagons, was now scattered with dismembered motor lorries. The slow carters, with their coatings of chaff and road dust, had been replaced by oil-faced repairmen and truck-drivers. In little over two years, this unchanged inn of Cervantes had become a repair depot for army vehicles. Indeed, in one corner, surrounded by an ardent group of greasy lads, they were even reassembling a captured Italian tank.