Relics

Relics

Copyright © 2005 by Mary Anna Evans

First Edition 2005

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2005921159

ISBN 10: 1-59058-119-9 Hardcover

ISBN 13: 978-1-61595-235-9 Epub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

To those who taught me to read and write

To all who understand the power of words

To everyone who ever shared with me a story that they loved

Contents

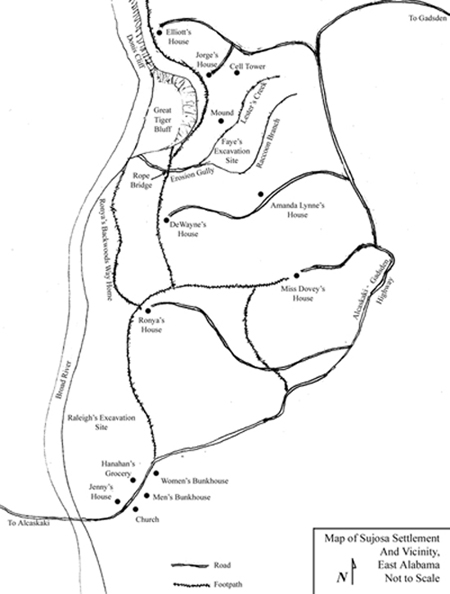

I’d like to thank everyone who reviewed Relics in manuscript form: Michael Garmon, Rachel Garmon, David Evans, Suzanne Quin, Carl Quin, Lillian Sellers, David Reiser, Leonard Beeghley, Mary Anna Hovey, Kelly Bergdoll, Diane Howard, Jerry Steinberg, the staff of the Mississippi Writing/Thinking Institute, the teachers and staff of Brentwood School and, especially, Assistant Chief William Davis of the City of Montgomery Fire Department, who ensured that Fire Marshal Strahan behaved as a firefighter should. I’d also like to thank Dr. Liana Lupas of the American Bible Society for her expertise, which greatly enhanced Miss Dovey’s song. Historical astronomy expertise was provided by the knowledgeable denizens of the HASTRO-L Internet discussion group. For communications questions, I relied on Thomas Farley, whose website

http://www.privateline.com

was particularly helpful, and Mark G. van der Hoek, a senior RF Engineer with a global consulting firm. Mark, a twenty-year veteran of the communications industry, went the extra mile in helping me keep the details of the Sujosa’s communications woes plausible. These people caught errors of the grammatical, logical, psychological, and ecological sort. All errors that remain are mine.

I owe Jenny Hanahan, Donis A. Casey, and my daughter Amanda a debt of gratitude for the use of their names. They bear no resemblance to the fictional characters named for them, although I do like those three characters a great deal and was glad to give them such lovely names.

Writing is both an art and a business, and I am grateful to everyone who has helped me improve my art and learn my business: Anne Hawkins, my agent; Robert Rosenwald and Barbara Peters, my publishers; Ellen Larson, my editor; the fine folks at Poisoned Pen Press—Jen Semon, Marilyn Pizzo, Monty Montee, Michelle Tanner, and Nan Beams; and my publicist, Judy Spagnola. And, finally, my eternal gratitude goes out to the booksellers who get my books out to readers, and to the readers who enjoy them.

Columbus could not have known how many people he would lead from the Old World to the New. The oceans were so wide and the new lands were so wild. At first, he—and the explorers who followed him—saw these lands only as obstacles barring the way to the spicy riches of the East. But then they learned of El Dorado. Many lives were spent in quest of a city with rooftops burning gold in the light of the setting sun.

In the end, the wealth of the Americas proved greater even than a fantasy city of gold. There was indeed gold in this New World, ready to be sifted from the ground or, more conveniently, stolen from the native kings. There were riches also to be had in the slave labor of those kings and their subjects. When the Old World tasted chocolate and maize and tomatoes and sweet, deadly tobacco smoke, still more fortunes were made. The wealthiest civilization the world has ever seen was built on the riches Columbus stumbled on by accident.

Not so long after Columbus’ fateful journey, a ship found harbor in the Gulf of Mexico. Its weary passengers gathered their belongings and began walking north, given the will to go on by the elusive dream of fortune. But they found no gold or silver, no wealth or prosperity. In the river valley where they stopped at last, there was only land—black earth and colored clay—but that was treasure enough.

Friday, November 4

Faye Longchamp was born on the first floor of a Tallahassee hospital built at an elevation of fifty-five feet above sea level. In the thirty-six years since then, she had never set foot on a taller hill. Her cherished home, a tumbledown antebellum plantation house called Joyeuse, was built for her great-great-grandfather by his slaves—some of whom were also her ancestors. It sat firmly on an island with a maximum elevation of seventeen feet, and few of its inhabitants ever strayed far from their coastal paradise. Faye herself had never, before today, left the low-lying Florida Panhandle. If the term “flatlander” was ever true of anybody, it was surely true of Faye.

This was the reason the gaping ravines that yawned along the Alabama roadside made her clutch the steering wheel of her twenty-five-year-old Pontiac in white-knuckled terror. When her tires rolled too close to the edge of the worn pavement, crumbles of asphalt slid down slopes that looked vertical to Faye’s flatlander eyes. And her tires rolled too close to the edge of the pavement with frightening regularity, because her barge-sized car was not built to maneuver hairpin turns. Faye had not expected Alabama to look like this. She made a mental note to never, ever venture into Colorado.

“Where are the guard rails?” she muttered. “How can they possibly build a road like this without guard rails? This is America. Somebody might get sued.”

Joe Wolf Mantooth sat in the passenger seat. Sometimes, the view out his window encompassed nothing but autumn-hued trees and a clear, meandering stream. Other times, the same window revealed a dizzying drop into the depths of a roadside precipice, but Joe always looked as relaxed as an old man after a good dinner. This was an accomplishment of sorts for a twenty-six-year-old.

“Want me to drive, Faye?”

Faye wanted to blurt out, “Are you kidding? You don’t even have a driver’s license,” but Joe didn’t deserve her rudeness. Instead, she said, “I can handle it.”

She wished she could tear her eyes off the road, because her peripheral vision was picking up glimpses of loveliness. Russet-hued sumacs stood flaming among persimmons and sweet gums that simply couldn’t decide what color they wanted to be. Their yellow and orange and purple leaves trembled like bits of glass in a kaleidoscope, framed by the laurel oak’s constant green. All her life, Faye had heard people raving about autumn leaves. Until now, she’d never understood what the fuss was about.

The trees on Joyeuse Island were predominantly palms and live oaks, with an occasional dogwood planted by some ancestor who enjoyed white flowers at Easter time. Live oaks got their name because they carried their green leaves through every season. Palm trees held onto their fronds until they turned brown and fell off. The dogwoods tried to put on a show, but Joyeuse’s short autumns made sure that each red leaf lasted about a day before it browned and dropped to the dirt.

Here in the southernmost reaches of the Appalachians, Faye was seeing autumn in all its glory for the first time, but enjoying it would have required her to take her attention away from the narrow, winding roadway. Convinced that doing so would bring certain death, she firmly insisted that the fluttering leaves stay in her peripheral vision.

Joe leaned back against the headrest and closed his eyes. His rhythmic breathing was the only sound in the car except for Faye’s occasional cursing of the civil engineer who designed the deathtrap roadway beneath her tires.

The ever-darkening sky wasn’t helping matters. Faye glanced at her watch. Sunset was still an hour away, but the sun was far on the other side of a mountain clad in autumnal clothing, and the trees’ garish colors weren’t bright enough to light the pavement ahead of her. She flipped on her headlights and goosed the accelerator.

Faye was eager to reach her destination for reasons that had nothing to do with the oncoming darkness or the treacherous road. Her new job as archaeologist for the NIH-funded Sujosa Genetic History and Rural Assistance Project—commonly called simply the Rural Assistance Project—excited her personally, as well as professionally. Here was her chance to do some important science, and to make a difference in the world, too.

As Faye had discovered while preparing for the job, the Sujosa had lived in an isolated valley in these hills since God was in kindergarten, and they held their secrets well. Their dark brown skin and Caucasian features suggested that they had arrived in Alabama sometime after 1492, but fringe theorists liked to argue that they might have beaten Columbus to the New World. Extreme fringe theorists thought they were one of the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Everyone agreed that they were settled in Alabama by Revolutionary times, because the word “Sujosa” appeared in several written documents of the era. Other documentary evidence proved that they had, at times, been deprived of the right to vote and own land, simply because their skin wasn’t white enough. First by law and then by custom, they’d been forced to worship separately from their white neighbors. Their children had been segregated into their own school until as recently as 1978, even after black children were finally admitted to white schools.

In fact, no one had ever given a tinker’s dam about the Sujosa—until a local doctor noticed that they didn’t get AIDS, even when they’d been exposed many times. When the issue of

Health

that carried Dr. Brent Harbison’s article hit the mailbox of the National Institutes of Health, the powerful and wealthy eye of the United States of America turned, for the first time, toward some of its weakest and poorest citizens.

The result was the Rural Assistance Project, whereby the NIH hoped to isolate the genetic basis for the Sujosa’s formidable immune systems, and give a hand to the Sujosa settlement at the same time. The NIH wanted to know where in Europe or Africa or Asia (or, for that matter, Antarctica) these people originally lived, and where they got their inherited ability to fend off disease. A geneticist, a linguist, an oral historian, and assorted technicians would work with Faye to dig up the Sujosa’s past, while an education specialist and a physician would work to help the land-poor Sujosa’s future.

The project was an archaeologist’s dream. And there could be no job more personally intriguing for a dark-skinned, Caucasian-featured archaeologist like Faye.

Faye glanced at Joe, who appeared to be sleeping, and smiled. It had taken quite a bit of wangling to get him on board the project as her assistant. Governmental agencies tended to be finicky about things like high school diplomas, and Joe didn’t have one. His paycheck would be absurdly small, compared to his value to the team, but sometimes money wasn’t the most important thing. She turned her eyes back to the road.

It couldn’t be far to the settlement now. She passed through Alcaskaki, the last town before the bridge, and saw that there wasn’t much to see—just a few city blocks of downtown surrounded by woodframe houses and farmland. On the far outskirts of Alcaskaki, the farmland petered out and a ravine opened up on the left-hand side of the road. To her right sprawled the county high school, a dusty collection of institutional buildings clustered protectively around a monumental football stadium. A bare handful of cars remained in the parking lot, its students having fled for the day.

Leaves, grown tired of living, dropped from the dimly lit branches above, through the bright cones of her headlights, and onto the roadbed—red, yellow, orange, purple, and gold. As she drove over them, her tires stirred them into the air again.

The object dropped out of the trees ahead, like a panther after prey. She threw the wheel violently to the left, and the car obeyed by veering hard, then skidding on the gravel scattered over the roadway’s crumbling pavement.

There was no time to study the thing as she passed under it. She retained only the image of someone dangling limp and blue-faced. Perched above was someone else, swathed in a hooded jacket. Beneath the hood, a dark face was lit by blue-green eyes the color of the luminous gulf waters around her island home. Then both faces faded out of sight, and she was fighting to regain control, thinking only of the deep chasm to her left. She heard the sound of shoes dragging over the roof of her car.

The Bonneville’s brakes squealed as they fought against the momentum the old car had earned through its sheer bulk. It might stop sliding toward the ravine’s sheer flank, and it might not, but the answer was a matter of physics. She and Joe were simply along for the ride.

***

The car skidded to a stop—dangerously near the edge of the ravine, but not in it. Dust rose around its tires as Faye jerked her door open and ran back along the road.

“What happened?” Joe said, running after her. His longer legs negated her head start and he was abreast of her within seconds. “Faye! Are you okay?”

“I think somebody’s hurt.” She pointed down the road.

Joe put on a burst of speed and reached the dangling form first, grasping it under its arms and lifting it to release the rope’s tension.

“It’s okay, Faye. Nobody’s hurt.”

“How can that be?” Then she saw what he held in his hands. Bottled-up fear turned to rage and she slapped the lifeless head as hard as she could. It was a papier-mâché dummy of a horned man wearing nothing but a banner that said, “Devils Go Home!”

“Somebody worked hard on this,” Joe said, bending its articulated joints with the appreciation of a fellow craftsman.

Faye wasn’t interested in the artistic quality of a prank that had nearly sent her and Joe to their deaths. She looked up into the tree, and into the darkening woods. There was no one there.

She pulled her father’s pocketknife out of her pocket and cut the devil’s rope. “I’m taking this with me so it doesn’t kill somebody. We have to track down the idiot who made it.”

“Nobody’s hurt, Faye,” Joe said again, as she hurled the loose-limbed devil into the Pontiac’s back seat. “That’s what counts. Let’s go.”

Faye took a deep breath and blew it out slow. Joe was right. When it came to the important things, like life and death and nature and spiritual stuff, he usually was. He seemed to have an esoteric Creek spiritual practice to suit every possible crisis of the soul. Faye’s expertise lay in practicalities, like paying the bills. When she got out of graduate school and finished renovating her two-hundred-year-old house and started putting some money aside for retirement, that’s when she’d have time to meditate on the meaning of human existence. In the meantime, she had Joe to take care of things like that for her.

“Yeah,” she echoed. “Nobody’s hurt, and that’s what counts.” She cranked her old car and pointed it toward the Sujosa settlement. She would have enough on her plate as it was without tracking down mysterious kids in hooded jackets. She was about to take on a job for which she was barely qualified, joining a team of seasoned professionals a month into the game. While somehow managing not to fall off these god-awful hills.

No pressure there. No pressure at all.