Replay: The History of Video Games (7 page)

Read Replay: The History of Video Games Online

Authors: Tristan Donovan

The rest of the video game industry watched the controversy carefully. While several distributors and arcade owners refused to touch

Death Race

, video game manufacturers kept quiet – preferring to see what could be learned from the controversy. The main lesson was that controversy sells. “The height of the controversy lasted for about two months then slowly died as other news stories became more important,” said Ivy. “During this time the demand for the game actually increased. We did have customers cancel their order while others increased their orders. The controversy increased the public awareness and demand for the game. Negative as it was, we felt the press coverage did increase the demand for the game and established Exidy as a major provider of video game products at that time.”

Around the same time as

Death Race

arrived in a blaze of controversy, Atari was enjoying major success with

Breakout

.

Breakout

came out of another of Nolan Bushnell’s attempts to instil a creative working culture at Atari: away days where staff would debate new ideas. “We’ll take the engineering team out to resorts on the ocean for a weekend or three days and do what we called brainstorming,” said Noah Anglin, a manager in Atari’s coin-op division. “Everything went up on the board no matter how crazy the idea was and some of them were really far out.” There was only one rule, according to Atari engineer Howard Delman: “Nothing could be criticised, but anyone could elaborate or enhance someone else’s idea.” At one of these away days someone proposed

Breakout

, a game that took the bat-and-ball format of

Pong

but challenged players to use the ball to smash bricks. “The idea didn’t meet our first clutch of games we were going to work on but Nolan really liked it,” said Steve Bristow, Atari’s vice-president of engineering. With Bushnell keen to see

Breakout

put into production, Bristow handed the job of developing the game to Steve Jobs, a young hippy who had taken a technician’s job at Atari so he could earn enough money to go backpacking in India in search of spiritual enlightenment. “Jobs always had a sense of his own self-worth that people found a little put off-ish,” said Bristow. “He was not allowed to go onto the factory floor because he wouldn’t wear shoes. He had these open-toe sandals that workplace inspectors would not allow in an area where there are forklift trucks around and heavy lifting.”

Atari expected the game to require dozens of microchips, so to keep costs low Jobs was offered a bonus for every integrated circuit he culled from the game. Jobs asked his friend Steve Wozniak for help, offering to give him half of the bonus payment. Wozniak, a technical genius who worked for the business technology firm Hewlett Packard, agreed. “Wozniak spent his evenings working on a prototype for

Breakout

and he delivered a very compact design,” said Bristow. Wozniak slashed the number of integrated circuits in half and netted Jobs a bonus worth several thousand dollars. Jobs, however, told Wozniak he got $700 and gave his friend $350 for its effort. Wozniak would only learn of his friend’s deceit after the pair formed Apple Computer.

Atari never used Wozniak’s prototype of

Breakout

. The design was too complex to manufacture and the company decided to make some changes to the game after he had worked on it as well. On release

Breakout

became the biggest arcade game of 1976 and the following year was included on the Video Pinball home games console.

[1]

But the rise of microprocessor-based video games, however, meant

Breakout

would be Atari’s last TTL game. Bushnell saw the microprocessor as the natural technology for the video game. “I made the games business happen eight years sooner than it would have happened,” said Bushnell. “I think my patents were unique and birre enough that it’s not for sure that someone else would have come up with something like it, but I’m sure that as soon as microprocessors were ubiquitous somebody would have done a video game system.”

The move to microprocessors also required a different set of skills from video game developers, shifting the focus away from electric engineers towards computer programmers. “Initially many of the programmers, including me, were also hardware engineers,” said Delman. “But after a few years, the two disciplines became distinct.” The need for programming skills prompted Atari to embark on a recruitment drive in 1976 to find the people who could make the new generation of video games.

One of these recruits was Dave Shepperd, the electrical engineer who had started making video games at home after playing

Computer Space

in the early 1970s. “By late ’75 and early ’76, it was clear to Atari the future was in microprocessors. They put an ad in the paper and I happened to see it,” said Shepperd. Prior to seeing the advert, Shepperd had begun experimenting with the Altair 8800, one of the very first microprocessor-based home computers. Available in the kit form via mail order, the Altair 8800 was nothing if not basic. Released in 1975 by MITS, it had no video output beyond a number of LED lights and just 256 bytes of memory.

[2]

It had no keyboard so users had to program it using a bank of switches on the front of the computer.

Despite its user-unfriendliness, thousands of computer hobbyists bought an Altair and set about building hardware and writing software for the system, which was powered by the same microprocessor used in

Gun Fight

. Among them were Paul Allen and Bill Gates who wrote a version of the programming language BASIC for the Altair and formed Microsoft to sell it. Shepperd, meanwhile, was making games for the system. “I designed and built a new video subsystem integrated into the Altair,” he said. “I got it working and coded up a few very simple games. Many of my neighbours would come over and we’d play games on it until the early hours in the morning. We’d make up new rules as we went along and I’d just patch them into the code and put them into the computer using only the toggle switches on the front panel and, later, from an adapted old electric typewriter keyboard I found in a dumpster.”

With his experience of writing games on a computer, Shepperd landed the Atari job and on Monday 2nd February 1976 he turned up for his first day of work bursting with excitement at the prospect of using the advanced computer equipment he imagined was lurking within Atari. “Atari’s cabinets looked real cool. The games were loads of fun. It seemed like the neatest, newest, most interesting thing I could be doing,” said Shepperd. “I had been working for a company that made products for IBM and Sperry Univac. The test equipment we had in our labs was pretty high end. The computers I was using were multi-million dollar IBM mainframes housed in very large climate-controlled, raised-floor computer rooms. For reasons I cannot explain, perhaps because the product was so new, I imagined Atari had engineering labs with even more state-of-the-art development tools and test equipment.” The reality brought Shepperd crashing back to earth: “The development labs were just tiny rooms in an old office building. The computer systems we had to use were third-hand PDP-11s. All of the test equipment we had was old and pretty beat up It was tough to find an oscilloscope with working probes. The office building had no air conditioning and with all the people and equipment jammed into the tiny office spaces it made the rooms almost unbearable, especially in the summer months. They were operating under a very limited budget and it seemed they were just keeping things together with chewing gum, bailing wire and spit.” Despite the conditions and ropey equipment Shepperd, like the other programmers who joined Atari at that time, was excited to be making games rather business software.

His first project was to make

Flyball

, a simple baseball game that did little to demonstrate the potential of the new era of microprocessor video games. But the second project he was assigned to,

Night Driver

, would ram home the potential of the new technology. Unlike earlier driving games such as

Gran Trak 10

and

Speed Race

, which were viewed from above,

Night Driver

would be viewed from the driver’s seat. The idea came from a photocopy of a flyer for another arcade game that Shepperd was briefly shown. “I have no recollection of what words were printed on the paper, so I cannot say what game it was and it could easily have been in a foreign language, German perhaps,” said Shepperd. “The game’s screen was only partially visible in the picture, but I could see little white boxes which were enough for me to imagine them as roadside reflectors.”

[3]

Not that Shepperd ever got to play the game that inspired

Night Driver

: “The flyer had nothing in the way of describing a game play. At no time did anybody suggest, either inside or outside Atari, how I was to make an actual game out of moving little white boxes around the screen. That I had to dream up on my own.” To work out how the game should look, Shepperd opted for learning from first-hand experience.

“I remember driving around at various times and various speeds – research, you know – watching what the things on the side of the road appeared to be doing as they passed my peripheral vision,” said Shepperd. His solution was to have the white boxes emerging from a flat virtual horizon and growing bigger and further apart as the player’s car moved towards them. Once the boxes reached the edges of the screen they disappeared. The first time Shepperd got the movement effect working, he and his boss were stunned. “The little white boxes spilled out from a point I had chosen for a horizon at ever increasing speed. We both sat there mesmerized by the sight,” he said. It was quite cool even though there was no steering or accelerator then. The project leader probably thought we had a winner right then and there but I wasn’t sure because at the time I still had no idea of how to score the game. All I knew was it looked really cool.”

Once Shepperd got the steering and acceleration working,

Night Driver

seemed destined to be a successful game. “One thing that nearly always was true at Atari, especially in the early days, was if the game was popular amongst the people in the labs, it was probably going to do quite well,” he said. “I often had to kick visitors off the prototype in order that I could continue with development. The visitors were not only other engineering folks, but word had spread and I had visitors from marketing and sales and all over all the time.”

Night Driver

introduced the idea of first-person perspective driving games, which are still widespread today, to a wider audience. The illusion of fast movement the game conjured up also showed just how microprocessors had released video games from the constraints of hardware-based design. But as well as ushering in changes in the arcades, microprocessors were about to alter the nature of home video games as well.

[

1

]. The Video Pinball console was a home

Pong

-type console featuring seven games, including

Breakout

,

Rebound

and four pinball games. The console was also released as the Sears Pinball Breakaway. In Japan, Epoch released it as the Epoch TV-Block in 1979.

[

2

]. Less than the memory used by an email with no text or subject line.

[

3

]. It remains unclear what the game on the flyer was, but the most likely candidate is

Nürburgring/1

, an arcade video game released in West Germany earlier in 1976 by the company Dr Ing Reiner Forest. Created by the company’s founder Reiner Forest and named after the famous German racetrack,

Nürburgring/1

pioneered the drivers’ perspective viewpoint used in

Night Driver

. Forest later created

Nürburgring/2

, a motorcycle-based driving game, and

Nürburgring/3

, a more advanced version of the original game. But by the early 1980s, Forest’s company had quit the video game business to focus on making driving simulations.

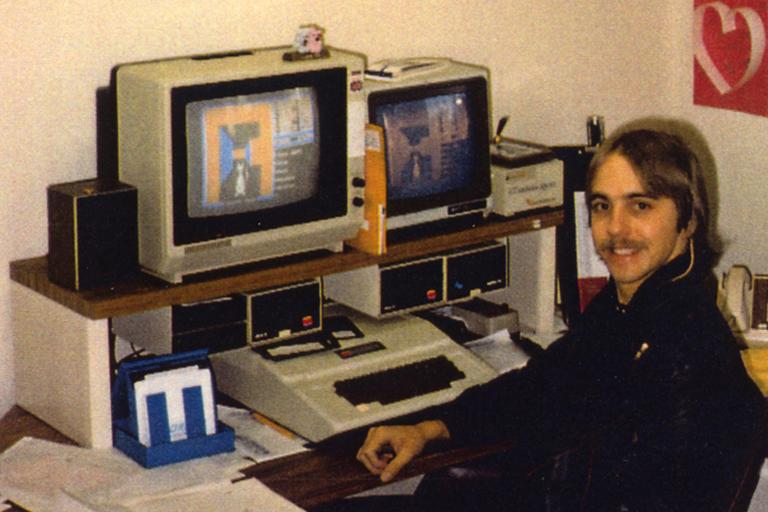

Dungeon master: Richard Garriott, aka Lord British. Courtesy of Richard Garriott

5. The Biggest Eureka Moment Ever

While the video game set about conquering the arcades of early 1970s, the birthplace of the medium – the computer – remained the preserve of the elite: sealed behind the closedoors of academia, government and business. Yet, unknown to players lining up to spend their loose change on

Pong

, video games were also thriving on the computer. The post-

Spacewar!

generation of computer programmers had picked up the baton of the Tech Model Railroad Club and begun to hone their coding skills by creating games.

Unlike their counterparts in Atari and Bally, these game makers faced none of the commercial pressures of the arcades, where the demand was for simple, attention-grabbing games designed to extract cash from punters’ pockets as fast as possible. Their only limitation was the capabilities of the computers they used. While the

Spacewar!

team enjoyed the luxury of a screen, most users were still interacting with computers via teleprinters even as late as the mid-1970s.

The reliance of teleprinters meant the only visuals their games could offer came in the form of text printed out on rolls of paper. “Whatever the machine had to say or display was printed on a narrow roll of newsprint paper that would click up the teleprinter painfully slowly,” said Don Daglow, who started making games while studying playwriting at Pomona College in Claremont, California. “We had a terminal that printed at 30 characters per second on paper 80 characters wide. It would print a new line every two seconds. It was so fast it took our breath away. When you’ve never seen it before it’s like magic – speed doesn’t enter into it.”

This lack of speed, however, ruled out the creation of action games similar to those in the arcades. Instead, computer programmers had little choice but to make turn-based games. The vast majority of these games were incredibly crude. There were countless versions of tic-tac-toe, hangman and roulette, dozens of copies of board games such as

Battleships

and swarms of games that challenged players to guess numbers or words selected at random by the computer. But as the culture of game making spread amongst computer users, programmers began to explore more innovative ideas. Soon players could take part in Wild West shoot outs in

Highnoon

, take command of the USS Enterprise in

Star Trek

, manage virtual cities in

The Sumer Game

, search for monsters that lurked within digital caves in

Hunt the Wumpus

and try to land an Apollo Lunar Module on the moon in

Lunar

. The action in all these games took place turn by turn, with the text describing the outcomes of each player decision pecked out slowly on teleprinters.

Even sport got the text-and-turns treatment, thanks to Daglow’s 1971 game

Baseball

. “Simulating things on computers was one of the things people did – if you read about something being done on a computer in a newspaper, very often you’d read they did a simulation of this or that,” said Daglow. “Once I understood what the computer could do, the idea of

Baseball

came from there – because baseball is such a mathematical game.”

[1]

Baseball’s simulation approach to sport was worlds away from the sports video games of the early arcades, which were, by-and-large, variations on

Pong

. Other programmers took the concept of simulations even further, pushing at the very limits of what could be regarded as a game.

Eliza

was one such experiment. Written in 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer science professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

Eliza

turned the computer into a virtual psychotherapist that would ask users about their feelings and then use their typed replies to try and create a meaningful conversation.

[2]

Although it was often unconvincing,

Eliza

’s attempt at letting people to interact with a computer using everyday language fired the imaginations of programmers across the world.

One programmer

Eliza

influenced was Will Crowther. Crowther was a programmer at defence contractor Bolt Beranek and Newman where he helped lay the foundations for the internet by creating data transfer routines for the US military computer network ARPAnet. In 1975 Crowther and his wife Pat divorced and his two daughters went to live with their mother. Crowther worried he was drifting away from his daughters and began searching for a way to connect with them. He homed in on the idea of writing a game for them on his workplace computer.

He based the game on the Bed Quilt Cave, part of the Mammoth-Flint Ridge caves of Kentucky that he and his wife used to explore together. He divided the caves into separate locations and gave each a text description before adding treasure to find, puzzles to solve and roaming monsters to fight. To make the game easy for his children to play he decided that, like

Eliza

, they should be able to use everyday English and got the game to recognise a small number of two-word verb-noun commands such as ‘go north’ or ‘get treasure’. Crowther hoped this ‘natural language’ approach would make the game less intimidating to non-computer users.

The result,

Adventure

, was a giant leap forward for text games. While

Hunt the Wumpus

let people explore a virtual cave and

Highnoon

had described in-game events in text, none had used writing to try and create a world in the mind of players or let them interact with it using plain English. Yet while his daughters loved the game, Crowther thought it was nothing special. After completing

Adventure

in 1976, he left it on the computer system at work and headed to Alaska for a holiday. It could have ended there. Disapproving system administrators regularly deleted games they found to save precious memory space on the computers they managed. Indeed many of the computer games created during the 1960s and 1970s were lost forever thanks to these purges. “Only a small minority actually survived,” said Daglow. “The ones that were on systems that got spread around by Decus – the Digital Equipment Corporation User Sety – are the most likely to have survived, in part because a lot of those were reformatted or republished in the earliest computer hobbyist magazines.” But while Crowther took in the icy sights of Alaska, his colleagues discovered

Adventure

and began sharing it with other computer users. Soon it began turning up on computer networks in universities and workplaces throughout the world.

In early 1977

Adventure

arrived at Stanford University where it caught the attention of computer science student Don Woods. “A fellow student who had an account on the medical school’s time-sharing computer had discovered a copy in the ‘games’ folder there and described it briefly,” said Woods. “I was intrigued and got him to transfer a copy to the artificial intelligence lab’s computer where I had an account. It was definitely different from other computer games of the time. Some computer games included the element of exploration, but they were generally abstract and limited ‘worlds’ such as the 20 randomly connected rooms of

Hunt the Wumpus

. The descriptions in Crowther’s game really drew me into it and the various puzzles hooked me.”

At the time it was common for the programmers to enhance or make alterations to games made by other people, after all no one had any expectation of making money from their creations. Woods believed he could improve

Adventure

and, after getting Crowther’s blessing, began to reprogram it.

He changed around the layout of the caves, added new puzzles to solve and made the dwarves of the original roam the caves at random rather than follow pre-defined routes. Woods’ roommate Robert Pariseau also contributed ideas for enhancements, one of which was to make a maze of indistinguishable caverns that Crowther created even harder to solve. By April 1977 Woods had completed his alterations. He made the new version of

Adventure

available for others to play and copy, and went away for the university’s spring break. Woods was in for a surprise when he returned. “I was told the lab computer had been overloaded due to people connecting from all over to play

Adventure

,” said Woods. The new version of

Adventure

generated even more interest than Crowther’s original and inspired others to write their own ‘text adventures’.

Among them were a four members of the Dynamic Modelling group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s computer science lab: Tim Anderson; Marc Blank; Bruce Daniels; and Dave Lebling. “We decided to write a follow on to

Adventure

because we were simultaneously entranced and captivated by

Adventure

and annoyed at how hard it was to guess the right word to use, how few objects that were mentioned in the text could actually be referenced and how many things we wanted to say to the game that it couldn’t understand,” said Lebling. “We also wanted to see if we could do one; this is a typical reaction to a chunk of new code or a new idea if you are a software person.”

Lebling had been making games for some time when the four decided to create their own take on

Adventure

, which they gave the work-in-progress title of

Zork!

. Unlike some of his computer game making peers he, as a student at MIT, had access to the one of the more cutting-edge systems of the era: the Imlac PDS-1. The Imlac could not only do graphics on its built-in display, but was one of the first computers that offered a

Windows

-style interface although it used a light pen instead of a mouse and required users to press a foot pedal to click. After making an enhanced version of

Spacewar!

and creating a graphical version of the previously text-only

Hunt the Wumpus

, Lebling started helping fellow MIT programmer Greg Thompson who wanted to update a game called

Maze

.

Steve Colley and Howard Palmer, two programmers at NASA Ames Research Centre in California, created

Maze

in 1973 on an Imlac. It took full advantage of the Imlac’s visual capabilities to create a 3D maze viewed from a first-person perspective that players had to escape from. Later Palmer and Thompson, who worked at NASA Ames at the time, changed the game so that two Imlacs could be linked together and players – represented by floating eyeballs – could move around the maze trying to shoot each other. When Thompson ended up leaving NASA Ames to join MIT’s Dynamic Modelling team in early 1974, he brought

Maze

with him. “

Maze

was based on a graphical maze-running game, Greg had brought from NASA Ames. We decided it would be much more fun if multiple people could play it and shoot each other,” Lebling said. The pair reworked

Maze

again so that up to eight people could play it at once. They created computer-controlled ‘robot’ players to make up the numbers when there weren’t enough real players and let players send each other text messages during while playing. Lebling and Thompson’s 1974 update of

Maze

pre-dated the online player versus player ‘death matches’ of first-person shooters, which would come to dominate the video games after the success of

Doom

, by nearly 20 years. “We actually played it a few times with colleagues on the West Coast, though ARPAnet was rather slow and the lag was horrible.

Maze

became so popular that the management of our group tried to suppress it,” said Lebling.

In stark contrast to

Maze

, however,

Zork!

– Lebling, Blank, Daniels and Anderson’s attempt to outdo Adventure – was a text only. To outshine

Adventure

, the quartet invented a new fantasy world to explore and improved on the writing of

Adventure

seeking to give

Zork!

a more literary feel. The four also reworked thay the computer read players’ instructions so that people could use more complex sentences, such as ‘pick up the axe and chop down the tree’ rather than two-word commands. After completing the game they renamed it

Dungeon

. It wasn’t long before the lawyers of TSR, the makers of the pen-and-paper role-playing game

Dungeons & Dragons

, came knocking.