Reporting Under Fire (23 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Europe gave Janine the chance to “live the life of a writer,” and she became a British citizen. Her marriage broke up, and free of anything to keep her feeling tied down, she left for Sarajevo, Bosnia, in December 1992, where the Serbian army had laid siege to the Bosnian civilians who lived in the ancient capital city. Sarajevo, once a glorious Old World city and host to the 1984 Winter Olympics, was also home to a cosmopolitan mix of Roman Catholics, Serbian Orthodox Christians, and Muslims who had worked together and lived in the same neighborhoods for years.

But the neighboring country of Serbia was on the march, determined to “cleanse” Sarajevo of its Muslim citizens. The Serbian Army had turned the city into a wasteland. Water lines ran dry. Electricity was unreliable. Food disappeared. Children, cooped up indoors for days on end, ran outside to play, and died, shot by Serb snipers. Janine arrived to see a Sarajevo in agony. W

ELCOME TO

H

ELL,

the graffiti greeted her as she was driven into Sarajevo. It was hell, indeed.

She stayed there for months. It was not lost on her or any other reporter in Sarajevo that genocide was taking place in Bosnia. They asked themselves how Europeans and their governments could allow this to happen. The Nazi Holocaust against Europe's Jews had unfolded fewer than 50 years before.

As Serbian artillery pounded Sarajevo from the mountainsides that surrounded the city, Janine moved into the Holiday Inn in downtown Sarajevo. It was hardly a hotelâhalf the building was a shot-out shellâbut a hardened news corps contingent lived there, reporters for big-name newspapers and magazines,

photojournalists, TV reporters, producers, and cameramen, plus an assortment of independent journalists such as Janine, who made a living going from war to war to get interviews and sell the stories to media outlets.

It was freezing cold. Most of the time the Holiday Inn had no heat, electricity, or running water. At night, Janine lit a candle in her fourth-floor room and typed her stories on a battery-charged word processor. Once per week she swapped packs of Marlboro Lights for a pail of hot water she hauled up the steps to her room so she could wash her hair. She and the assortment of reporters, camera crews, and producers who lived in the Holiday Inn ate rice and cheese scrounged from humanitarian food deliveries. Sometimes dinner was chocolate bars and whiskey. To entertain themselves, the more daring hotel guests rappelled from the top floors of the hotel into the lobby below.

The Holiday Inn sat at the end of a street nicknamed Snipers' Alley, and when carloads of journalists went to work, they roared out of the hotel's underground garage at full speed to avoid getting shot. Janine was an indie journalist without a car, and she begged rides with TV journalists whose staff always had armored cars. “CNN's truck was always full,” she recalled, “and they had the reputation of helping no one but their own. The BBC people, however, were more generous, and they usually waved me into the back of their truck. âGet in, hurry up.' The back of the car smelled of gasoline from the stores of petrol in tin cans.”

Then one hot August day she got the nod to go to Zuc, the battle line where the final battle to defend Sarajevo on Gogo Brdo, Naked Hill, took place.

And during those long, hot August days, there were dead men on Naked Hill. Most of them were very young. They

were soldiers, they had been killed, and it was too dangerous to remove their bodies. And so they lay where they fell, in the shimmering heat. The men who came down from the trenches for resupply every few days said the smell of the dead wafted down into the trenches where the living cowered, waiting for the next round of gunfire. I did not know what the dead smelled like when they rotted in the sun, but a year later, in Rwanda I would understand it: I would see rows and rows and rows of bodies, the dead mothers holding their children stiffened by rigor mortis, fathers with their eyes melting from the heat, and I would remember again Naked Hill.

The siege of Sarajevo and the war in Bosnia affected Janine di Giovanni in a way no future war zones ever would. Janine, who twice met the legendary war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, learned an essential piece of wisdom about the life she had chosen: “Martha Gellhorn once wrote about loving only one war and the rest being duty. I still feel like thatâBosnia was the war that took and broke my heart in a million little pieces.”

In Bosnia, Janine met hundreds of hungry, suffering people, families who had lost parents, grandparents, and children. The desperation of the very young and the very oldâthe truly help-lessâespecially grabbed at her heart. She befriended several, including Nusrat, a small Muslim boy living in an orphanage, and Zlata Filipovic, a 13-year-old girl whose wartime diary was the talk of journalistsâthey called her the “Anne Frank of Sarajevo.” When the diary was published in English in 1994, Janine wrote an introduction recalling the days she spent with Zlata and her familyâhow Zlata's mother, a chemist before the war, was slowly going mad; how the family hid in a “safe room”

when the Serbs shelled their neighborhood; how Zlata pointed to the snapshot of her standing with a small friend who was killed, a gesture of remembrance.

It was also in Bosnia that Janine fell in love with a French television cameraman named Bruno Girodon. They had no real future togetherâtheir jobs took them to far-flung corners of the worldâand the handsome Frenchman with the bewitching green eyes had a longtime girlfriend who, when she learned about Janine, insisted that he never contact Janine again.

Janine moved on. She turned 30, 32, and then 35, earning her living by traveling to war zones to speak with the people caught between opposing sides and telling their stories in magazines and newspapers across Europe and North America. One could track her travels by the articles and books she wrote, long pieces for

Vogue, Vanity Fair,

and the

Times of London

Sunday edition, reporting from Bosnia, Lebanon, Israel, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Zimbabwe, and Sierra Leone. The titles of her books speak of the life she ledâ

Against the Stranger: Journeys Through Occupied Territory

;

The Quick and the Dead: Under Siege in Sarajevo; Madness Visible: A Memoir of War; The Place at the End of the World: Stories from the Frontline.

Then, in 2003, she ran into Bruno Girodon again. The old fires still burned. He asked her to marry him and have a baby, and she agreed. Janine wore a sleeveless, tea-length dress and white gloves at their wedding, which took place in a small Catholic church in the south of France. Then she and Bruno parted waysâhe had work to do in Africa, and Janine, pregnant, wanted to make a trip to Jerusalem to interview Palestinians who were caught up in the second intifada, another uprising against Israel. When she got to Jerusalem, her own life turned upside down as she began to have troubles with her pregnancy.

One Israeli doctor warned her that she must stay in bed; a second doctor said that it was safe for her to go home to London for surgery and wait out the pregnancy there.

She packed up and left for London, had the surgery, and late in her pregnancy, she and Bruno moved to Paris where they planned to raise their child. Baby Hugo arrived in the spring, early but healthy. Now Janine craved a “bubble of happiness,” a safe and perfect place where she, Bruno, and little Hugo could nest together. But that bubble flew away, far from her grasp.

Janine began to feel fear, as some new mothers do, and developed a ferocious need to protect her baby at all costs. She behaved as though she lived in a war zone instead of safe in her Paris home, which Bruno had so lovingly built for her. She hoarded cash, wrote out escape plans, and stuffed her diaper bag as if she were heading on a long, dangerous journey. Any stranger presented a possible threat. Born a Catholic, Janine went into churches and lit candle upon candle, praying for her dead father and dead brothers and praying that God would keep her little family safe. As she recuperated from an exhausting pregnancy and the first trying days of caring for a newborn, she also had to think about her future: Would she return to work as a foreign correspondent?

Janine needed to ask herself if she was addicted to the thrill of working from a war zone. Bruno urged her to go to work, assuring her that getting back in the field would help her to find out. In late summer of 2003, when Hugo was six months old, Janine flew into Iraq, where the US Army had removed Saddam Hussein from power that spring. She went to work in Sadr City, a slum outside Baghdad where insurgents had rebelled against the American military.

Janine learned a lot about herself on that trip. She missed her baby desperately, and an Iraqi official reminded her that she

should not miss his first steps or lost tooth. But going through that experience braced her, and she returned to Paris sure that she wasn't addicted to her work in war zones. She made a well-considered decision: she would continue to work as she had before, but now she would cram into five days what would have taken a month to accomplish before.

Then their lives changed again. After Hugo was born, Bruno's back failed him, and he suffered for months. One day he left for a doctor's checkup and didn't come home. Janine received a phone call that threw her into confusion.

“He's suicidal,” the doctor told her. Janine could not believe what she'd heard. Bruno was in a psychiatric unit. When she got him on the phone he said to her, “I'm so tired.” Several weeks passed until he came home from rehab.

Like her husband, Janine had watched people suffer. Bad memories stayed with her, especially the pain or loneliness of children. The first time she had watched a gravely injured child crawling on a cot, she had gone outdoors and vomited. Yet over time Janine had disciplined herself when she was on the job to watch, ask questions, and take notes. Only when she was alone would she allow herself to cry, hold her head in her hands, or just stare at the ceiling.

When she returned from a war zone she did not talk about the places she'd been. She didn't like questions about how many dead bodies she'd seen or whether she'd been raped. Her memories “went into black bound notebooks and the notebooks went into a box and the box went into the basement. From there, I could look at them someday and remember all the people, the places, the red dirt, the rain, and the mud. But for now, I was fine. I always thought Bruno was too.”

A psychiatrist had told Janine that her resilience and her writing had helped her to cope with the horrors she witnessed. She

wasn't a candidate for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Bruno, however, wasn't built the same way. Like warriors returning from the battlefield, he suffered from PTSD. It was not just physical pain that plagued him; he was having a mental breakdown. Bruno Girodon had watched human suffering through the lens of his television camera for 20 years, and it had taken its toll. He tried to cope with his illness by rehabbing a new flat for Janine and their son, working like a madman in spite of the discs disintegrating in his back.

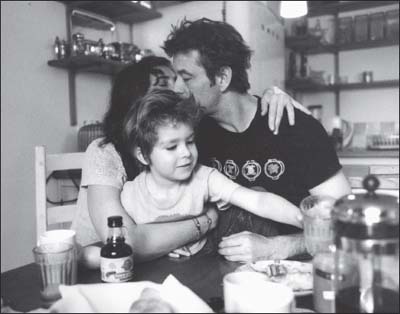

Janine di Giovanni, Bruno Girodon, and their son Hugo.

Courtesy of Janine di Giovanni

Janine learned that five times as many war correspondents as ordinary people exhibit signs of PTSD after living and working in such frightful settings. Bruno showed every one. He was deep into depression. He couldn't sleep and spent entire nights

drinking bottles of wine and listening to jazz. Clearly he was an alcoholic, but for the time, Janine couldn't confront that fact as she watched her husband crumble in front of her. Denial was a family tradition; the di Giovannis didn't talk about unpleasant matters. Not until Bruno was nearly arrested for driving drunk could Janine shake herself loose and confront the grim fact that her husband was an addict.

Bruno reentered rehab and then joined Alcoholics Anonymous to help himself manage his illness. He became so obsessed with AA that he practically abandoned Janine and their child for those he met at AA. They separated, agreeing that Hugo would have both of them in his life. Janine makes sure that her son is in the safe, loving care of his father or his nanny when she goes to the field.

Many would question how she could leave her son for such dangerous work, but Janine felt that her work was equal to her responsibility at home. Now, a decade later, Janine continues her mission: to bear witness to scenes of war so that readers can grasp the grim reality of how ordinary people live amid bombs and bullets and to give these forgotten a voice.

When the work demands it, she travels. When she's home and her son is at school, she researches, interviews, and writes from their flat in Paris. She is their breadwinner, living what she calls a “hand-to-mouth existence,” though Janine admits it's a “privileged” way to earn her living.

She receives enormous satisfaction from doing what she loves. As much as she has loved her child's father, she “never wanted to be dependent on a man,” she said. “When my father died, my mother didn't know how to write a check.” Her dry humor came over the phone as she spoke of a woman friend, a banker who stated flatly, “I never want a man to buy my knickers.”