Resurrection Man (30 page)

"I'll bet!" Dante laughed painfully. "Was it as good as you thought it would be?"

"Not bad," Jet allowed. "Not bad at all."

I

N TRUTH WE KNOW NOTHING, FOR TRUTH LIES IN THE DEPTH.

—D

EMOCRITUS

EPILOGUE

As I write this I am sitting in the fort we built on Three Hawk Island. Warm soft summer surrounds me, and the low throb of cicadas makes the air shake and sigh; makes the willow fronds twist and untwist before me.

Soon I will have to row back across the river to the house. Dante and Laura are waiting. There's a wedding rehearsal planned for three, and it would be in poor taste for the best man not to attend. So, I must leave my fort in the willow tree, the hidden place where I am king, and go once more to stand on the outskirts of Dante's life; to smile and make polite applause.

Who knows? Perhaps next year it will be me, walking down the aisle. The magic is rising all the time; life is short, but full of possibilities. And if I do find a mate for my strange heart... will she be dour and deliciously jaundiced, an expert at

The Times

crossword puzzle? Or a broad-shouldered blonde in hiking boots to help me escape into a wilder life of clouds and rivers?

If I do marry, I'll get the better of the bargain, for Dante will make far funnier speeches at my wedding than I could ever make at his.

* * *

Portrait

When I took my most important portrait, I thought I was only shooting a landscape. Such are the ironies of life!

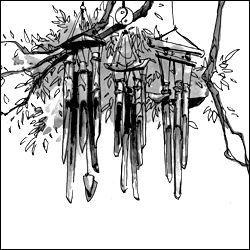

It was late on a summer's day much like this one. I had started out to give the fort another coat of waterproofing, but the magic of the afternoon entrapped me. I pulled up the western blind and sat on the rail with my back against a big branch and one leg swinging lazily in space. Below me the river split and hurried foaming around the tip of Three Hawk Island. A mild summer breeze lazed through the air; thin willow leaves slowly turned and twisted like charms on a green bracelet; bamboo chimes thin as birds' bones clicked together and swung apart, singing snatches of a summer song. A delicious smell of wood and mud and water rose from the eddy beneath my feet, and sunlight dripped like honey down the willow fronds.

By chance—or maybe fate—I had a roll of color film in my camera. Clambering down on impulse, I took the runabout and put-putted fifty yards upstream. Then, drifting with the river's current, I focused on the great, green, melancholy willow and took this shot. You can just see the huge branches spreading out behind waterfalls of twisting green; midway up and a little to the left a red-lacquer pagoda peeks through, our fort. It could just as easily be a trysting place for lovers, perhaps; or the hermitage of an ancient sage.

Overhead, vast unknowable clouds build and dissolve in a vaster sky, deep summer blue.

I didn't know it was a portrait until much later.

Two hundred years of life: according to Dante, that's what Pendleton was playing for when he laid down his faked full house, aces over eights. Confidence paid a cheat with a cheat, I guess. Year after year the willow's black roots pierced and encircled my father's body, drawing him into themselves, making him part of the tree. No doubt he'll get his two hundred years.

I do not think trees live in time as we do; they last too long.

Time changes things. Pendleton's mistake when he cheated at cards, or Dr. Ratkay's death: at first, such things seem devastating, losses that will cripple you forever.

Time passes.

The branch broken withers and dries. New limbs branch into the emptiness where the old bough flourished. In three years, or five, what was a mutilation has become only a landmark, and a pattern of growth.

A man lives in his eyes, glinting and skipping over the surface of his days, spinning down the stream of time, each moment in the grip, of.a changing current, a different eddy; dazzled by the play of light on water.

A tree stands still. Time moves slowly, for it lives at the roots of things; any lesson that takes less than years to teach is difficult for a tree to grasp. Grief lingers, and the ache of loss: those things don't change. But seeping into every leaf, a little guilt burns away each autumn, and falls, spinning down the river. Winter's long sleep begins, and with each spring the tree wakes knowing mercifully less than it did the year before.

I have always loved the great willow. I love to lie in the fort and listen to its sighs and silences, its long slow melancholy. .. .

Beyond the southern window of the fort there is such a glory of sun and shifting leaves this summer day I have to squint, dazzled, and turn away. Leaf-shadow twists and untwists in my little wooden room. Cicadas sing. The river runs and runs below; and despite myself I am content, if only for a little while.

For was it not a thousand days my father held me after all?

Did he not rock me to sleep a thousand times in his strong arms?

T

HE

E

ND