Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation (21 page)

Read Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation Online

Authors: Sean Bodmer

Tags: #General, #security, #Computers

Let’s take a closer look at each of these principles.

Focus

It is all about the adversary decision maker. In a deception, the person who makes the decisions, allocates resources, and approves strategic decision making is the person the deception should be tailored to affect. All others fall short because the ultimate purpose of the deception is to have the adversary allocate, waste, or improperly spend resources in a way more favorable to your efforts.

Focus can be used against an individual or group. When the focus is on the individual, it’s tailored to deceive that individual. When the focus is on a group (such as organized crime or a foreign government), it’s about the leadership of the group infiltrating your network—the frontline attackers report all of their findings up through a chain of command, and someone in that chain makes decisions based on the intelligence collected.

The importance of focus is directing the decision maker into making the wrong decisions or decisions of your design.

Objective

The goal is to get the adversaries to act or not act; you don’t want to just tell them a nice story.

Perhaps we project a story that there is an unopened bottle of high end Johnny Walker sitting on the bar and it is available for free—first come, first served. Say that we know the adversary decision maker is a connoisseur of Scotch whiskey and loves high end products. That is a nice story, but is it enough to get the adversary to go to the bar himself?

When relating the principle of objective to the cyber world, think about developing a project or system that may be of interest to a threat. You need to design a deception operation that will interest your adversaries and lead them to act and fall into your deception.

Centralized Planning and Control

Each deception should be coordinated and synchronized with all other deception plans to present a seamless story across the organization. Overlooking the smallest detail could prove fatal.

Perceptual consistency is one of the most important goals of deception, especially when dealing with a highly skilled and motivated threat. Consistency can be built into many areas from personnel, logistics, financial, and technical resources and assets.

The adversaries must see a seamless story that is compelling enough based on all the intelligence they have collected from your enterprise. Essentially, you want to make the threat feel comfortable enough to take an action against your deception. The slightest innocuous detail can ruin an entire deception operation. For example, if John is listed as a member of a team that is associated with the deception, and John is transferred to another location but is still listed in the deception as being at his original location, the adversary will more than likely come across the discrepancy and not act, which defeats all of your efforts and resources to build the deception.

Security

One seller of high end Johnny Walker will not tell you that next door there is a sale on the exact same product. In the same vein, why would you want to deliberately give away information regarding the true deception story? The mere fact there is a deception should foster a heightened level of security.

Operations security (OPSEC) of your deception is critical to ensuring success and the ability to continue to your end goals. Securing your deception is of the utmost importance. A slight error or oversight can breach the security of your deception against a threat.

Timeliness

If we cannot get across the message to our adversary that the high end Johnny Walker is all teed up and ready to go, which would prompt him to take action, our efforts are lost in the blink of an eye. Having him show up the following day or week may do us no good at all, and may actually be detrimental to ongoing efforts.

Always have the right message delivered at the right time to the right person through the right conduit. When building a deception plan, you need to ensure each portion of the initiative is released on time and is consistent with every other component or operation of your organization.

For example, if you allow a threat to steal information surrounding a deception regarding a new system that is being built, and specific details on the network location of this system are embedded in the content of the stolen data, the threat may move quickly and act on the latest intelligence. So if your bait systems are not set up properly (or not at all), you have failed in your objectives.

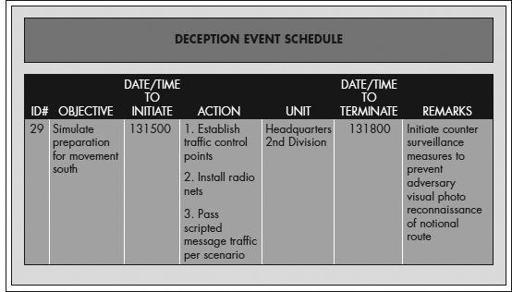

The following shows an example of a simple format planners can use to track and schedule the actions required to make the deception successful.

Joint Publication 3-13.4, Military Deception

Integration

No effort should ever be a stand-alone effort; it should be fully synchronized and integrated into ongoing factual efforts, as well as other deceptive efforts.

When building a deception plan, you need to factor in production or operational resources that will need to be leveraged to ensure perceptual consistency to the threat. If you stage bait systems that simply sit in a corner of your network, without any context or activity, they will serve no purpose. Threats may understand you are watching and waiting, and could alter their patterns or behavior.

In order for deception to truly be effective, you should incorporate a coordinated effort and leave trails and traces of the deception across your organization and even partner or subcontractor networks. This builds on perceptual consistency to an attacker. A good example would be your chief executive officer (CEO) sending out an organization-wide e-mail stating that a new initiative is being kicked off and announcing the program and specific individuals who will be working on this project. This would require your finance, administration, operations, and human resources departments to incorporate portions of data within their groups in order to provide the perceptual consistency to the threat. If threats do not feel comfortable, they will not act.

Traditional Deception

This section presents several historical uses of deception as they apply to military combat or operations, as well as how each applies to the cyber realm. One of the most important things to realize is that the tactics do apply to cyber attacks. As the defending force of your enterprise, you should do the most you can to minimize the risk to your enterprise by leveraging these examples and applying them to your organization‘s security policy.

Feints—Cowpens

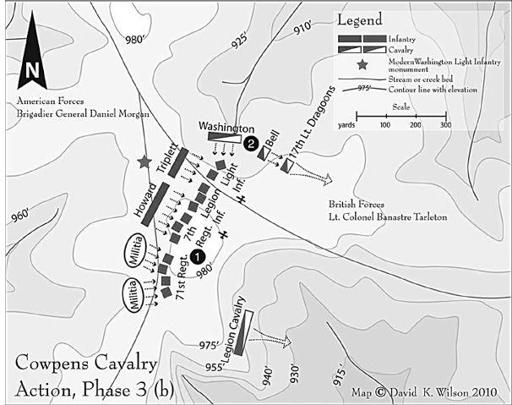

For those of us who were around in 1781, there is a lesson here about feints that could involve a shot of scotch to prep the objective. General Nathaniel Greene, commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army, appointed Brigadier General (BG) Daniel Morgan to take up position near Catawba, South Carolina, between the Broad and Pacolet Rivers. BG Morgan knew his adversary, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Tarleton, well. Additionally, he knew the readiness level of his regulars and militia, as well as his

adversary’s perceptions

of his force’s condition. In a previous engagement, the militia had barely stood their ground in the face of the hardened British regulars, and BG Morgan knew he could use this perception to draw LTC Tarleton and the British Legion into a trap. BG Morgan placed his troops in three rows: the first was the sharpshooters, the second was the militia, and the final row was the Continental Army regulars.

The plan was to feign LTC Tarleton and lure him in through a series of controlled engagements. Two bouts of engagement and withdrawal would deceive the British Legion members into believing they were in control of the battlefield. Sadly for LTC Tarleton, there was no recovery from the route, and there was a great Continental Army victory at the pivotal battle known as the Battle of Cowpens.

Applying to Cyber

When it comes to boundary, perimeter, and internal systems and applications, you can feint almost anywhere. You can control the terrain better than your threat, as you

should

always have control of your physical systems (even if they are located at a remote site). A feint in the cyber realm would be placing weak systems at various high-value target nodes or points of entry into your enterprise. This could provide threats with a false sense of confidence and security, which could lead to mistakes on their end.

Demonstrations—Dorchester Heights

Now let’s take a look at the Siege of Boston in 1775 and how a demonstration secured yet another victory for the colonials.

In April 1775, militia men surrounded the British garrison in Boston and kept the soldiers at bay for 11 months. It was the opening stage of the Revolutionary War, and General Washington knew the artillery recently captured by Nathan Hale at Fort Ticonderoga would be just what he needed if it was placed in the right location: Dorchester Heights. This area was recognized by military commanders as key terrain because of its commanding position over Boston. From there, the captured artillery could reach not only the city, but as far as the harbor. Strategically located, this position could not be reached and was never threatened by British artillery.

General Washington sent a young Colonel Henry Knox to Ticonderoga to collect all the captured British artillery and bring it back to Boston. In March 1776, Colonel Knox returned and placed the artillery in plain view of the British forces. The Continentals worked throughout the night and in the morning, and the British forces had quite a surprise. Just the presence of the guns led the British commander, General Howe, to take action. In a short time, General Howe evacuated his forces, never to return to Boston.

General Washington didn’t need to do anymore than show the guns in a demonstration to gain the tactical advantage. He actually didn’t have the munitions to fire most of the guns—a minor technicality, one would say.

Applying to Cyber

Demonstrations of superiority are common, as governments around the world show off their latest and greatest weapons and technologies. Every year, reports are leaked of some intrusion that could be state-sponsored and/or organized by a foreign government. This indicates that there is knowledge of the events and that they are being monitored. Whether or not action is taken against the threat operating abroad (which is seldom), that is a demonstration of force to protect assets.

Ruses—Operation Mincemeat (the Unlikely Story of Glyndwr Michael)

Glyndwr Michael was a vagabond and a Welsh laborer who perished after ingesting rat poison in a London warehouse. His life was quite unremarkable until after his death. That was when he assumed the persona of a soldier named “Major Martin.” The remaking of Glyndwr Michael was to become part of one of the most elaborate ruses in military history.

It was 1943, and the Allies were looking to make their way into Sicily, but with strong German and Italian fortifications and troop density, the task seemed a bit overwhelming. British Naval Intelligence was up to the task of creating a deception to help the troops in the field. They were favored with the insight of a brilliant staff officer, Ian Fleming, who devised the plan after remembering an old spy novel he had read years before.