Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (6 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

The Lisa team decided to optimize their display for horizontal resolution, in order to be able to display 80 columns of text in an attractive font. The vertical resolution wasn't as important, because vertical scrolling works much better for text than horizontal scrolling. The designers decided to endow Lisa with twice as much horizontal resolution as vertical, using a 720 by 360 pixel display, with pixels that were twice as high as they were wide. This was great for text oriented applications like the word processor, but it made things somewhat awkward for the more graphical applications.

When Burrell redesigned the Macintosh in December 1980 to use the same microprocessor as Lisa, the Motorola 68000, it set off shock waves within Apple. Not only was Burrell's new design much simpler than Lisa, with less than half the chip count, but it also ran almost twice as fast, using an 8 megahertz clock instead of a 5 megahertz clock. Among other advantages was the fact that the Mac's 384 by 256 pixel display had the identical horizontal and vertical resolution, a feature that we called "square dots". Square dots made it easier to write graphical applications, since you didn't have to worry about the resolution disparity.

Bill Atkinson, the author of Quickdraw and the main Lisa graphics programmer, was a strong advocate of square dots, but not everyone on the Lisa team felt the same way. Tom Malloy, who was Apple's first hire from Xerox PARC and the principal author of the Lisa word processor, thought that it was better to have the increased horizontal resolution. But Burrell's redesign moved the debate from the theoretical to the pragmatic, by creating a square dots machine to compare with the Lisa.

The Lisa hardware was scheduled to go through a final round of design tweaks, and Bill tried to convince them to switch to square dots. He mentioned his desire to Burrell, who responded by working over the weekend to sketch out a scaled up version of the Macintosh design that featured a full 16-bit memory bus with a 768 by 512 display and square dots, that would also run twice as fast as the current Lisa design. Bill convinced the Lisa engineering manager, Wayne Rosing, that he should at least consider adopting some of Burrell's ideas, and arranged for the leadership of the Lisa team to get a demo of the current Macintosh, and learn about Burrell's new scaled-up design.

Wayne Rosing led a delegation of his top hardware and software guys over to Texaco Towers for a demo on a Monday afternoon, including hardware guys Rich Page and Paul Baker and software manager Bruce Daniels. We ran various graphics demos, with Bill Atkinson doing the talking, and then Burrell gave a presentation on the Mac design, and his ideas for scaling it up to 768 by 512 display. Everyone seemed pretty impressed and Bill was optimistic that they would make the change.

After a few days, Bill told us the disappointing news that Wayne had decided that there wasn't enough time to embark on such a radical redesign, since at that point the Lisa was scheduled to ship in less than a year. It ended up shipping around two years later with the original 720 by 360 resolution and relatively slow microprocessor, which became a problem when Apple decided to offer a Macintosh compatibility mode for Lisa in 1984. The emulation software didn't try to compensate for the different resolutions, so the applications were distorted by the resolution disparity, almost like looking at a fun-house mirror. It would have continued to be a problem for Apple if the Lisa hadn't been discontinued in 1985.

Round Rects Are Everywhere!

by Andy Hertzfeld in May 1981

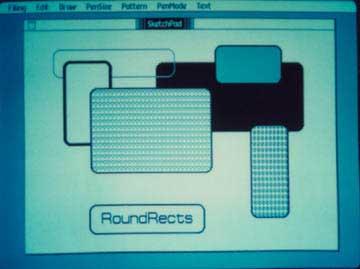

Bill Atkinson worked mostly at home, but whenever he made significant progress he rushed in to Apple to show it off to anyone who would appreciate it. This time, he visited the Macintosh offices at Texaco Towers to show off his brand new oval routines, which were implemented using a really clever algorithm.

Bill had added new code to QuickDraw (which was still called LisaGraf at this point) to draw circles and ovals very quickly. That was a bit hard to do on the Macintosh, since the math for circles usually involved taking square roots, and the 68000 processor in the Lisa and Macintosh didn't support floating point operations. But Bill had come up with a clever way to do the circle calculation that only used addition and subtraction, not even multiplication or division, which the 68000 could do, but was kind of slow at.

Bill's technique used the fact the sum of a sequence of odd numbers is always the next perfect square (For example, 1 + 3 = 4, 1 + 3 + 5 = 9, 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 16, etc). So he could figure out when to bump the dependent coordinate value by iterating in a loop until a threshold was exceeded. This allowed QuickDraw to draw ovals very quickly.

Bill fired up his demo and it quickly filled the Lisa screen with randomly-sized ovals, faster than you thought was possible. But something was bothering Steve Jobs. "Well, circles and ovals are good, but how about drawing rectangles with rounded corners? Can we do that now, too?"

"No, there's no way to do that. In fact it would be really hard to do, and I don't think we really need it". I think Bill was a little miffed that Steve wasn't raving over the fast ovals and still wanted more.

Steve suddenly got more intense. "Rectangles with rounded corners are everywhere! Just look around this room!". And sure enough, there were lots of them, like the whiteboard and some of the desks and tables. Then he pointed out the window. "And look outside, there's even more, practically everywhere you look!". He even persuaded Bill to take a quick walk around the block with him, pointing out every rectangle with rounded corners that he could find.

When Steve and Bill passed a no-parking sign with rounded corners, it did the trick. "OK, I give up", Bill pleaded. "I'll see if it's as hard as I thought." He went back home to work on it.

Bill returned to Texaco Towers the following afternoon, with a big smile on his face. His demo was now drawing rectangles with beautifully rounded corners blisteringly fast, almost at the speed of plain rectangles. When he added the code to LisaGraf, he named the new primitive "RoundRects". Over the next few months, roundrects worked their way into various parts of the user interface, and soon became indispensable.

Pineapple Pizza

by Andy Hertzfeld in May 1981

Our reward

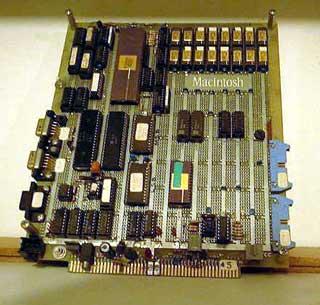

When I began working on the Mac project in February 1981, there was still only one single 68000-based Macintosh prototype in existence, the initial digital board that was wire-wrapped by Burrell himself. It was now sitting in the corner of Bud Tribble's office, on one of the empty desks, attached to a small, seven-inch monitor. When powered up, the code in the boot ROM filled the screen with the word 'hello', in lower case letters and a tiny font, rendered crisply on the distinctive black-on-white display.

Dan Kottke and Brian Howard were already busy wire-wrapping more prototype boards, carefully following Burrell's drawings. In a week or so, I received the second prototype for my office, so I could work on the low level I/O routines, interfacing the disk and keyboard, while Bud worked on the mouse driver and porting Bill's graphics routines.

The next big step for the hardware was to lay out a printed circuit board. We recruited Collette Askeland, the best PC board layout technician in the company, from the Apple II group. Burrell spent a week or two working intensely with Collette, who used a specialized CAD machine located in Bandley 3 to input the topology and route the signals, eventually outputting a tape containing all the information needed to fabricate the boards.

Burrell and Brian Howard checked and rechecked the layout, which was tediously expressed as thousands of node connections, and after a day or two they decided they were ready to send it out for fabrication. We were hoping to get the first sample boards back before the weekend, but it looked like they weren't going to make it. Finally, around 4:30pm on a Friday afternoon, they arrived.

Burrell figured that it would take at least two or three hours to assemble a board, and then even longer to troubleshoot the inevitable mistakes, so it was too late to try to get one working that evening. Maybe they would come in on Saturday to get started, or maybe they'd wait until Monday morning. While they were discussing it, Steve Jobs strolled into the hardware lab, excited as usual.

"Hey, I heard that the PC boards finally arrived. Are they going to work? When will you have one working?"

Burrell explained that the boards had just arrived, and that it would take at least a couple of hours to assemble one, so they were thinking about whether to start tomorrow morning or wait until Monday.

"Monday? Are you kidding?", replied Steve, "It's your PC board, Burrell, don't you want to see if it works tonight? I'll tell you what, if you can get it to work this evening, I'll take you and anyone else who sticks around out for Pineapple Pizza."

Steve knew that Pineapple Pizzas had recently replaced Bulgarian Beef as Burrell's current food obsession (which, as a staunch vegetarian, he thought was a positive development) and that Burrell wanted a Pineapple Pizza pretty much every chance he could get. Burrell looked at Brian Howard and shrugged. "OK, we may as well give it a shot now. But I don't think we'll be able to get it working before the restaurants close."

So Burrell and Brian got busy, selecting a board and stuffing it with sockets, carefully soldering them in place, while five or six of the rest of us, including Steve, sat around and kibitzed. Burrell seemed a little tense and impatient, since he didn't like the pressure of bringing up a board in front of so many spectators. Every five minutes or so, he referred to the awaiting Pineapple Pizza, speculating about how good it was going to taste.

Finally, around 8pm or so, the board was assembled enough to try to power it on for the very first time. The prototype was hooked up to an Apple II power supply and a small monitor, and fired up as we held our breath. The screen should have been filled with 'hellos', but instead all that was there was a checkerboard pattern.

We were all disappointed, except for Burrell. "That's not too bad", he commented, "It means the RAM and the video generation are more or less working. The processor isn't resetting, but it looks like we're pretty close." He turned to look directly at Steve. "But I'm too hungry to keep working - I think it's time for some Pineapple Pizza."

Steve smiled and agreed that it was good enough for the first night, and it was time to celebrate. The seven or eight of us who stayed late drove in three cars to Burrell's favorite Italian restaurant, Frankie, Johnny and Luigi's in Mountain View, ordering three large Pineapple Pizzas, which tasted great.

I Invented Burrell

by Andy Hertzfeld in 1981

Burrell had a great sense of humor, and he was capable of performing devastating impersonations of everybody else on the Mac team, especially the authority figures.

Whatever idea that you came up with, Jef Raskin had a tendency to claim that he invented it at some earlier point. That trait was the basis of Burrell's impersonation of Jef.

Jef had a slight stammer, which Burrell nailed perfectly. Burrell began by folding his fingers together like Jef and then exclaiming in a soft, Jef-like voice, "Why, why, why, I invented the Macintosh!"

Then Burrell would shift to his radio announcer voice, playing the part of an imaginary interviewer. "No, I thought that Burrell invented the Macintosh", the interviewer would object.

He'd shift back to his Jef voice for the punch line.

"Why, why, why, I invented Burrell!"

Macintosh Prototypes

by Daniel Kottke in June 1981