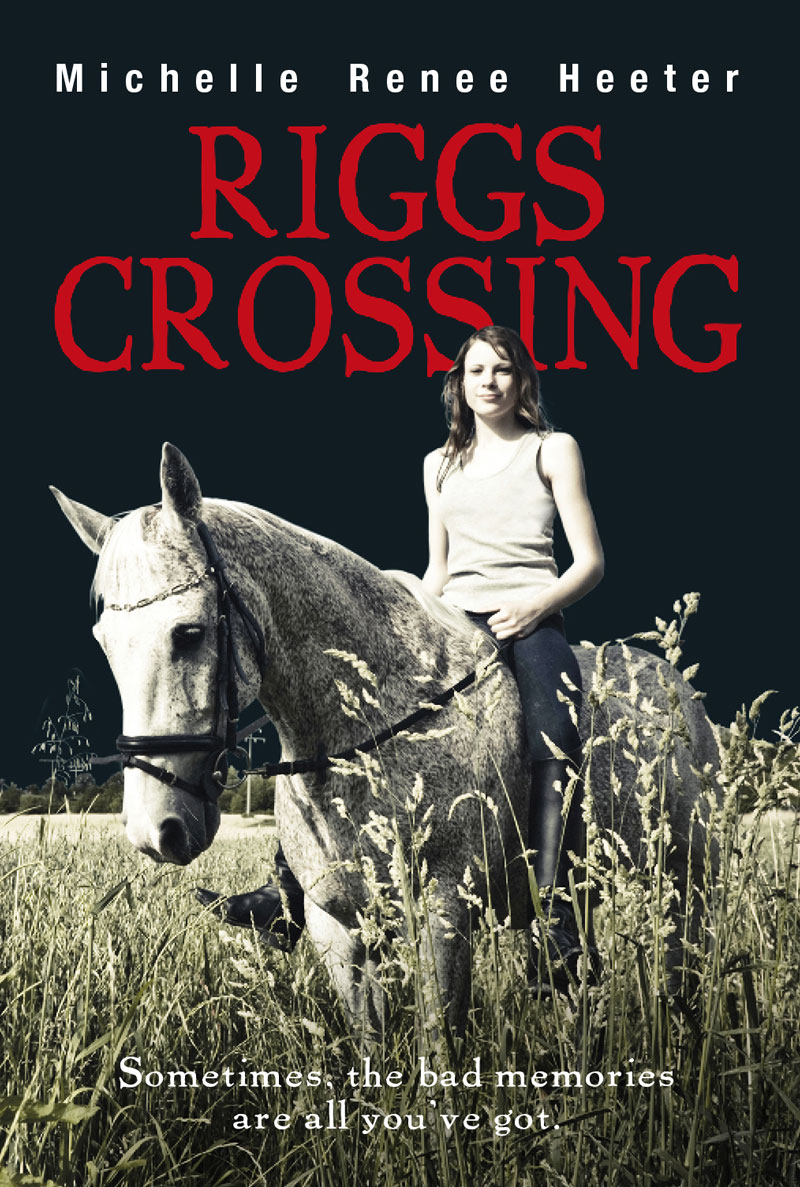

Riggs Crossing

Authors: Michelle Heeter

- PROLOGUE

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

RIGGS CROSSING

Michelle Heeter

Riggs Crossing

Michelle Heeter has written short fiction for Australian magazines That’s Life and Family Circle under the pen name Renee Dunn. Her work has also appeared in the American titles True Story and True Confessions. Michelle has been a full-time technical writer for the past several years, and enjoys working with software developers.

Michelle grew up in the American Midwest. After earning a master’s degree from Michigan State University, Michelle left America for good. She moved to Japan, where she was a lecturer in English for six years. Michelle was living in Kobe when the 1995 earthquake struck. Five weeks later, she moved to Australia.

Michelle loves cats and dogs, swims, practises yoga, wishes she could go horseback riding more often, and commutes to work by bicycle. She lives a short walk from the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

This book is dedicated to my high school English teacher, Mr. William Murphy. I owe special thanks to Dyan Blacklock and Meredith Costain, along with all the readers and editors who helped make

Riggs Crossing

a better book.

First published by Ford Street Publishing, an imprint of

Hybrid Publishers, PO Box 52, Ormond VIC 3204

Melbourne Victoria Australia

© Michelle Heeter 2012

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This publication is Copyright. Apart from any use as permitted

under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by

any process without prior written permission from the publisher.

Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be

addressed to Ford Street Publishing Pty Ltd, 2 Ford Street,

Clifton Hill VIC 3068.

www.fordstreetpublishing.com

First published 2012

Dewey Number: A823.4

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication

data:

Heeter, Michelle, 1964–

Riggs crossing / Michelle Heeter

ISBN: 9781925000641 (pbk.)

For young adults.

Accident victims – Fiction.

Cover design: Gittus Graphics ©

Printing and quality control in China by Tingleman Pty Ltd

PROLOGUE

Case Summary

Samantha Rose Patterson [aka Len Russell]

Adolescent female, age approximately fourteen, found alone and suffering serious injuries in the wreckage of a car near Wollomombi. Police contend Samantha’s father, suspected commercial marijuana grower Michael Patterson, was murdered by rival drug traffickers, although the body has not been found and no charges have yet been laid. Spent bullet casings, bloody clothing, and other signs of a violent altercation were found near the scene of the accident.

No identification was found in Samantha’s possession. Her birth seems never to have been registered, her name does not appear on Medicare records, and she is not enrolled at any school in New South Wales. Hospital staff called her ‘Len Russell’, a nickname that seems to suit her androgynous appearance and manner and with which she seems comfortable.

Samantha was positively identified after a police investigation led officers to the isolated logging town of Riggs Crossing, where a handful of local residents admitted knowing Samantha after being shown photos of her taken during her hospital recovery. The information gained from the people of Riggs Crossing about Samantha was sparse and grudgingly provided, fuelling the suspicion held by police that Samantha’s father was involved in criminal activities that led him to his violent death.

Samantha reacted badly when two social workers attempted to explain what police had learned about her identity and past, verbally abusing the caseworkers and exhibiting compulsive hand-washing behaviour over the next several days. As a result, it was decided to continue addressing Samantha as ‘Len Russell’ and allow her to recover her memories in her own time.

Samantha appears well-nourished and is recovering quickly from the injuries sustained in the auto accident. Nevertheless, she exhibits a confusing, even contradictory, range of physical and psychological symptoms with no clear etiology. Samantha claims not to remember anything prior to waking up in hospital. However, CAT and MRI scans show no evidence of concussion or brain damage sufficient to cause cognitive impairment or memory loss. The examining neurologist and psychiatrist agree that Samantha is either (1) suffering from hysterical amnesia following the emotional shock of her father’s violent death, or (2) refusing to discuss her past due to fears of reprisals from her father’s killers, or out of distrust of law enforcement and other authority figures.

Two months after the accident, Samantha underwent a range of psychometric tests. Samantha’s verbal ability, spatial visualisation, and mathematical reasoning skills were measured by a team consisting of a cognitive psychologist and a representative from the Department of Education. Samantha cooperated fully and seemed to enjoy the testing process. Results indicate that Samantha’s intelligence is in the top ten per cent of the population.

Samantha’s emotional health is less easy to determine. She presents as a well-spoken but reserved teenager who appears most comfortable dealing with adults in structured, formal situations. Samantha, during her stay in hospital, was observed avoiding interactions with patients her own age. When such encounters were unavoidable, Samantha behaved in a surly and abrasive manner, perhaps in an unconscious attempt to mask her own social anxieties and poor interpersonal skills.

Elements of Samantha’s behaviour observed by hospital staff indicate at least some degree of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Samantha maintains an elaborate personal hygiene routine and registers disgust at others’ actual or perceived lack of cleanliness. One nursing sister observed that while Samantha never asked personal questions or engaged in small talk, she expressed interest in the disposal of contaminated waste, asked how hospital equipment was sterilised, and paid close attention as her room was cleaned and disinfected each day. Samantha has maintained a rigorous attention to personal hygiene since her discharge from hospital. Resident caseworkers at the Inner West Youth Refuge report that Samantha takes at least one shower a day, keeps her room meticulously ordered, and exhibits moderate anxiety at the less stringent personal habits of other children at the Refuge.

Anita Gibson, Samantha’s mother and the former de facto partner of Michael Patterson, went missing in 1998. Anita Gibson was a known hitchhiker and was last seen near Bellingen. Anita Gibson’s remains, identified through dental records, were found in New England National Park, where the notorious backpacker killer murdered at least four of his victims.

Police investigations revealed that Samantha Patterson’s nearest known relation is her maternal grandmother, Mrs Rose Gibson. Mrs Gibson, who has suffered from a psychiatric disorder since learning of her daughter Anita’s death, lives in a Housing Commission flat in Campbelltown. Mrs Gibson has unresolved anger toward Anita for abandoning the family and is ambivalent about meeting Samantha. Anita’s three surviving siblings all wish to establish a relationship with Samantha but are fearful of the effect this would have on Mrs Gibson.

It was arranged for Samantha to be placed at the Inner West Youth Refuge. IWYR is a youth care facility of an experimental and sometimes controversial nature. IWYR receives funding from government and private sources. IWYR’s non-intrusive philosophy and high carer/child ratio was judged best suited to an adolescent who is recovering from physical injuries, suffering from psychological trauma, and resistant to psychotherapy.

It is normal practice for children and adolescents to be reunited with their families or moved into foster homes as soon as possible. However, in view of the sensitive nature of Samantha’s case, it has been agreed that Samantha will remain at IWYR indefinitely.

Chapter 1

I wake up with the sun shining through the cracks in the dusty, crooked blinds. Down the hall, other girls are using the showers and toilets. I need to go, but I close my eyes and hold it in. I usually wait until everyone’s been gone a while before I go to the bathroom, because fat Karen always leaves the place smelling like a sewerage treatment plant. Considering how much she eats, she probably drops a huge elephant turd every morning. Wouldn’t that be the definition of a home, a place where you don’t mind the smell of the other people who’ve gone to the toilet before you? Where there are proper curtains on the windows, not dingy blinds? No matter how homely they try to make this place, it looks, smells and feels like what it is: an institution.

I hear Bindi and Cinnamon laughing about something as they head off to the kitchen. A minute later, I hear Karen slam the toilet door behind her, then go clomping down the hallway on her camel feet, each huge paddle sending reverberations through the whole house.

Stomp clomp stomp clomp stomp clomp.

Fat moron.

I look at the clock radio. Eight-twenty. I roll over onto my side and draw one knee up toward my chest, which for some reason makes my full bladder less uncomfortable. I close my eyes and try to remember what the bathroom was like where I lived before the accident, but end up falling back to sleep.

It’s just after sunrise on a winter morning and I don’t want to get out of bed, but I’m busting for a wee. I put on my shoes and coat and walk through the cold house. When I open the door to the lounge room, a blast of warmth hits me in the face. Someone left the kerosene heater on. I tiptoe through the lounge room, past a woman sleeping on the couch under a leather jacket. The ashtray on the coffee table is full of cigarette butts and there’s a plastic juice bottle with a piece of garden hose coming out the side and dirty water in the bottom. A man with a beard is snoring in an armchair. I step on a beer can and it makes a crunching sound. The woman shifts and pulls the jacket over her head, the man mumbles something in his sleep. I cross the room, walk through the kitchen, and go out the back. Twenty paces through long grass and I’m there. The smell is bad. I leave the door open even though my teeth are chattering, partly to let in some air and partly because I’m afraid of spiders. No one can see me – the dunny faces away from the house. In front of me, across the canyon, is endless forest and sky and mist. We are on the edge of the escarpment that drops to the river below. The Nymboida River.

‘Len? Are you awake?’

Nymboida. Escarpment.

The vision fades and the words fly away as Lyyssa, the Resident Counsellor, pounds on my door and I remember how badly I have to go to the toilet.

Chapter 2

I’m at the Inner West Youth Refuge. They brought me here after the accident. Not right after the accident – I spent a month in hospital, floating in a painkiller haze while surgeons put me back together again – but when the doctors said I was ‘well’ enough to go home.

I don’t know where my home is, if I even have one. That’s why they sent me here.

At least I know my name, my nickname, anyway. When they found me, I was wearing a jumper with ‘Len’ stitched over the heart. Would that mean my proper Christian name is Leni? Helen? Elaine? And my surname is anybody’s guess. They put it down as ‘Russell’ on my papers, because I was wearing a Russell Athletics T-shirt. Pretty stupid, if you ask me. What if I’d been wearing Tommy Hilfiger?

On my first night here, Karen asked me why I couldn’t remember anything. I told her I’d taken a bump on the head in a car wreck, because Karen didn’t look smart enough to understand the truth.

There’s no such thing as ‘bump on the head’ amnesia – that’s something that only happens on TV. Dr Mengers explained it to me when I was still in hospital. If I’d taken a knock on the head severe enough to cause memory loss, there would be evident brain damage. I don’t have any brain damage, and the test results prove it. They’ve taken squillions of CATs and MRIs and other assorted tests with fancy names. Sometimes I had my head hooked up to electrodes, sometimes I had to drink a whole glass of chalky-tasting glop, sometimes I had to lie still for an hour inside some scanner that reminded me of a tube-shaped coffin. All of those tests said the same thing: my brain survived the accident unharmed.

It’s my soul that got knocked around.

Hysterical amnesia was the official diagnosis. That’s why Dr Mengers referred me to Lyyssa. I have an appointment with Lyyssa in a few minutes, and I’m looking forward to it like I’d look forward to having a tooth pulled or getting a tetanus injection.

Lyyssa is a psychologist and a social worker. She lives at the Youth Refuge with us, and I’m supposed to see her privately for an hour once a week. I know Lyyssa means well, but our sessions seem kind of pointless. Dr Mengers is good at taking complicated ideas, like ‘synaptic transmissions’ and ‘declarative memory’ and ‘consolidation in cortical networks’ and explaining them in simple terms. Lyyssa is just the opposite. She takes simple ideas, and explains them in the most complicated words possible. Instead of ‘acting out’, Lyyssa talks about ‘maladaptive coping responses’. Instead of ‘praise’, Lyyssa talks about ‘positive reinforcement’. I bet Lyyssa wishes she was a neurologist, so she could have an excuse for using multi-syllable words all day.

I leave my room, walk down the hall and pass through the common area where Karen is sitting in front of the TV like an obese toad, staring at the screen with her mouth slightly open. Karen is about ten years old with frizzy red hair sprouting from a huge, pumpkin-shaped head that’s attached directly to her neckless blob of a body.

‘An insect’s exoskeleton serves as a protective covering,’ someone on the TV is saying. ‘The exoskeleton also functions as a surface for muscle attachment, and as a sensory interface with the insect’s environment.’

What the person on the TV means is that the exoskeleton is for the bug what a normal skeleton is for us, and that the bug can feel things through its exoskeleton, like we feel and see and hear. But Karen doesn’t understand any of this. That person talking on TV could be saying that a bug’s exoskeleton is made of the same stuff as the chocolate coating on a Magnum ice-cream, and Karen wouldn’t know any different. She’s just watching the TV for something to watch. She might as well be watching a goldfish swimming around in its bowl.

Ignoring Karen, I go down another hall, past the so-called library with its dog-eared books and broken computers. Next is the supplies room where Sky Morningstar, a Non-Resident Counsellor, is showing Jo, a new Non-Resident Counsellor, where to find stuff. Lyyssa’s office is the room on the end. I hesitate a moment, then knock.

‘Hello, Len.’ Lyyssa opens the door to her office. ‘Come in and have a seat. I’ll be with you in a moment.’ Today, Lyyssa’s wearing jeans and a Big Day Out T-shirt. I can’t believe that Lyyssa really went to Big Day Out. Dressing like a kid just out of high school is one of her transparent techniques to make her more ‘accessible’, and so all the better to ‘relate to’ juvenile clients like me.

With Dr Mengers, I feel like a patient. With Lyyssa, I feel like a laboratory experiment.

I sit down at the table and study the only poster on Lyyssa’s wall that interests me: the illegal drug chart. Most of Lyyssa’s posters are illustrated with cute animals, hot air balloons, or rainbows, and feature vaguely inspirational quotations. But the drug poster just lays things out and lets you decide what to think.

Drug: cannabis, also known as marijuana, mull, pot, grass, weed. Usually smoked in a hand-rolled cigarette (joint, reefer) or a water pipe (bong). Active ingredient: THC. Effects: relaxation, euphoria, increased appetite, reduced inhibitions. Causes paranoia in some individuals. Long-term side-effects: decreased fertility in males after prolonged heavy usage

. To the right of the chart is a picture of a cannabis leaf, some dried marijuana, and a fat joint.

‘So,’ Lyyssa says, taking the seat opposite me, ‘why don’t we start with you telling me about your week.’

I can’t see the point of this, as Lyyssa knows everything I’ve done this week, but I tell her anyway. ‘Um, on Monday I went with you to a school and I took some tests.’

Lyyssa nods encouragingly. ‘And what else?’

‘Well, on Sunday you drove us to the Westgardens Metro.’ Every other week, Lyyssa drives us to a shopping centre so we can spend our pocket money.

‘Did you have a good time?’ Lyyssa asks.

That’s difficult to answer. I was having a good time, in spite of Bindi and Cinnamon sticking together and making rude comments about everyone, but then Karen pissed her pants and we had to cut short our trip. Karen has some weird form of diabetes that makes her wee every five minutes if she forgets to take her medicine. It wasn’t much fun riding home in the van sitting next to Karen, who smelled like a dirty nappy.

‘Yeah, it was all right.’

‘And what else happened to you this week?’ Lyyssa prods.

I got up. I went to bed. In between, I ate and watched television. I worried that they’ll make me go to the same school as Bindi and Cinnamon. Yesterday, I walked around the neighbourhood and looked at all the old houses. This morning, Bindi told me not to touch her skateboard or she’d kill me, even though I was only looking at it.

‘Nothing, really,’ I say to Lyyssa.

A few more minutes of this and I’m allowed to leave. As I close the door to Lyyssa’s office behind me, I see Sky Morningstar and Jo leave the storeroom. I hang back until they disappear around the corner of the hallway, chatting about paperwork and house rules. I’m not sure what Sky Morningstar or Jo do, exactly. They help Lyyssa somehow. They’re both vegetarians. Sky Morningstar is small and pretty, with curly brown hair and brown eyes. She wears skinny jeans and black Converse All-Stars. She’s here four days a week. Jo is taking over from somebody who recently left. Jo will be here one day during the week and on the weekends. She is tall and pale, and wears long plain dresses that come to her ankles, long strings of wooden beads, and thick sandals. She brings her laptop with her to the Refuge and works on it in the dining room.

I wonder what to do with myself for the rest of the day. This morning, I got some paper towels and spray cleaner and cleaned the grime off the blinds in my room, then I got a knife and scraped off all the stupid Lila-Rose & LeeLee stickers that the previous occupant of my room had pasted all over the desk. Lila-Rose & LeeLee Nelson, the tanned, blonde, skinny Malibu Twins. They have their own TV show, their own line of clothing, and starred in four straight-to-video movies. LeeLee went solo for a while and recorded her own CD before she went into treatment for anorexia. Then Lila-Rose went into rehab for alcohol and drug dependence. Tweens all over the world have girl-crushes on both of them. How vomitous.

Karen told me that a girl named Kim used to have this room, but Karen didn’t know what happened to her. Probably, Kim got sent to the Planet for Dorks Who Like Lila-Rose & LeeLee.

In the Refuge, there are safe and unsafe places, safe and unsafe times. I feel safe in my own room with the door shut. When Bindi is gone, I feel safe.

Bindi has hated me since the moment I got here. I don’t know why. Bindi is about fifteen. She’s not what I’d call pretty, but she’s dark and thin and striking, like one of those models in fashion magazines who’s made up to look sick and heroin-addicted. Bindi has papered her walls with pictures of those blank-eyed models that she’s torn from magazines. Whoever decides what goes in those stupid magazines needs to have a look at the methadone clinic a few blocks up the street from here. Then they’d get a clue as to what heroin-addicted really looks like. Real junkies don’t wear ropes of gold necklaces or shoes that cost five hundred dollars.

Bindi has decided that she’s bound for better things than this boring Refuge, like being a dickhead fashion model or a ‘high-class hooker’ (that’s another look that the fashion mags love), so she’s trying to be as troublesome as she can so they’ll let her go. She breaks the house rules, is rude to Lyyssa, bullies Karen, and is working out what she can do to intimidate me. She hasn’t really done anything to me yet except stare at me in a mean way and make a few threats, like the one about her skateboard. I keep quiet when she’s around and pretend I’m not afraid of her. If I don’t show her anything, if she doesn’t know what I want or what I care about or what I’m afraid of, she won’t know how to get at me.

Cinnamon is Bindi’s little hanger-on. Cinnamon is more conventionally pretty than Bindi, with thick brown hair that falls to her waist, a straight nose, and a bee-stung mouth. She’s a bit heavy, but I’ve seen guys turn and stare at her boobs and butt. It’s her eyes that ruin her looks. They’re big, brown, and empty. In one of the old magazines in the library, there’s an interview with a dog breeder who talks about Irish setters, which have been bred for their looks for so many generations that they no longer have any brain to speak of. ‘Those dogs are so dumb, they get lost on the end of their leads,’ the breeder said. That dog breeder could have been talking about Cinnamon.

Cinnamon’s lack of intelligence is probably why she follows Bindi around. I don’t have to worry about Cinnamon unless Bindi is here.

Anyway, both of them will be at school until around four. I decide to have another look in the library, even though my first look in there didn’t exactly thrill me. I open the door and look at the books, some of them lined up neatly, some just piled on top of each other. There are all the standard-issue kids’ books, from

Winnie the Pooh

to

Little House on the Prairie.

Nothing new there for me. I move on to the next shelf.

Sweet Valley High, The Baby-sitters Club, The Saddle Club

, and, wouldn’t you know it,

A Twinning Team

, by druggy Lila-Rose and skinny LeeLee. Modern trash for tweens.

Tweens.

Nobody who is a tween would want to be called a tween. Anyway, I’m older than a tween.

I move on to the next shelf. Issues of Christian magazines probably sent to us by the Foundation, the group of church people who started the Refuge and who are still partly in charge of it. A stupid-looking kids’ book called

Bessie Bunton Joins the Circus

, with a picture of a fat girl in a tutu on the cover. A dozen or so yellowed and dusty volumes of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books. God knows where those came from. And why would anybody want a

condensed

book? Then there are the brightly coloured paperbacks, obviously bought by Lyyssa, stuff about self-esteem and life choices and mapping your own destiny. These are all in mint condition.

There are a few Mills & Boon novels and a few historical romances. When I came in here the other day, I opened one written by a lady named Serena Delacroix because it had a picture on the cover of a dark-haired man pashing a girl who looked like Cinnamon, but it was so embarrassing I had to stop reading. The story was about Riana, a young English noblewoman who’s kidnapped by a pirate named Cade. The beginning was kind of boring, so I skipped some pages and ended up reading the part where Cade forcibly takes Riana to his bed. She sobs and says she hates him, but secretly realises that she loves him and desperately hopes that she has conceived his son. I closed the book feeling embarrassed to be female. Before I put the book back on the shelf, I wiped the cover with my shirt so that no one can ever find my fingerprints on it and prove that I touched such a stupid book. I have to wonder, who owned that book to begin with, and why the hell did they give it to us?

There are rows of old school textbooks: algebra and trigonometry and history and grammar. A few books seem utterly pointless:

Advanced Machine Quilting, Colour Schemes for Australian Homes

, and

Birthday Cakes for Children.

As I come to the end of the third bookshelf, I see three huge boxes of books stacked on top of one another in the corner. Probably, no one has got around to sorting them yet. The boxes are too heavy for me to lift, so I open the flaps of the top box, pull the books out a few at a time, and set them on the table.

I have hit the jackpot.

I tiptoe to the door and close it very carefully, so that the latch doesn’t even click. Then, working as quietly as possible, I sort the books into three piles.

OKAY

These are the ones I’m too old for, or too young for, or that just don’t interest me. I also put schoolbooks and cookbooks into this pile.

CRAP

All the Mills & Boon-type books go into this pile, along with condensed books, religious stuff, and stupid girl books. Just when I think I’ve got the CRAP sorted, I find

So Rich, So Famous

by June Collins and two

Star Trek

books. Three more for the CRAP pile.

MINE

These are the good ones. Or at least they look good. They say you can’t judge a book by its cover, but what choice do you have? There’s a book on Chinese astrology and a smaller paperback on regular astrology. The dust jacket of the Chinese astrology book is blood red, with black lettering and a gold stencilled picture of a dragon. There are a couple of biographies that look interesting. The biography of Georges Sand is perfectly new – I can tell by the stiffness of the pages that no one has ever opened it.