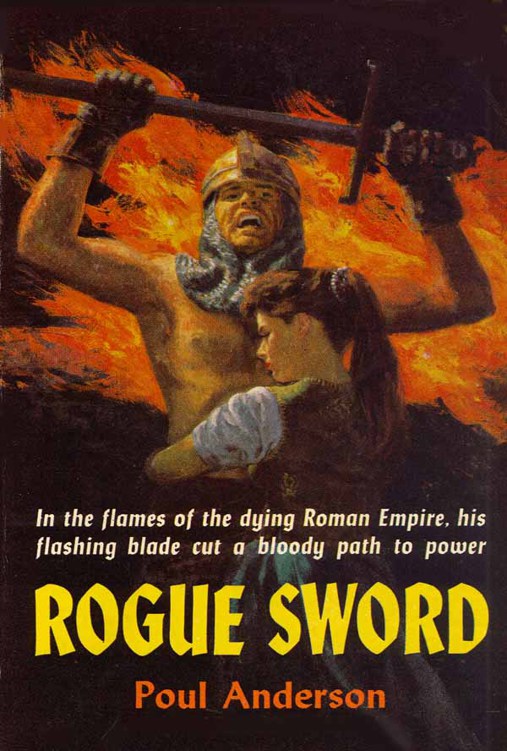

Rogue Sword

Poul Anderson

Copyright ©1960, by Poul Anderson

An Avon Original

As he sprang through the window, Lucas heard steel whistle at his back. For an instant, he wondered if the sword had reached him. Then he was falling through darkness.

He straightened in midair and hit the canal in a clean dive. The water shut thickly above his head. Memory stabbed: thus had he often gone over a certain low cliff, into the sea that encircled Crete. And when he came up, the waves had glittered, unrestful blue to the world’s rim, and had laughed with him. Was it only four years ago?

He felt himself rising, and struck out underwater. When his lungs were near to bursting, he broke the surface. A piling was rough beneath his hand, supporting him in part. The house it upheld gave him a helmet of shadow. He felt the water warm and oily on his skin. It stank. No, he thought, Venice lies far from Crete.

Cautiously, he glanced around. Thin night-mists lay on the canal, unreal beneath stars and a bit of moon. The houses lifted sheer from narrow walkways, doors barred, windows shuttered, blind with sleep. Yards behind and above him, one square shone with dull candlelight. The bulky black form of a man leaning out filled most of it. A metal gleam jumped about in his hand. Fear vanished in mockery as Lucas thought: If he failed to skewer me, why must he vent his anger on the unoffending air?

Then the merchant began to shout.

“Custodi! Ho, custodi!”

Echoes clamored from wall to wall and back again, down the length of the canal. A squad of watchmen could not be far away; this city was well patrolled. Lucas bit his lip in returning unease.

Another shape appeared at the second-floor window. The candle-glow touched her body and her unbound hair. She screamed above her husband’s bellowings, “Lucco, get away! He’ll have you blinded--” Gasparo Reni snarled and shoved her back into the chamber.

Did torches bob as men came jogging along the walkway, somewhere off in the fog? Lucas didn’t care to find out. Moreta was quite right, bless her soul. Bless also her eyes and lips and arms and ... He reminded himself sharply of his peril. Worse, in a way, than before. If Gasparo had slain him and thrown him into the canal (who would ask that great merchant what he knew about the fate of a penniless orphan apprentice?) he would at least be dead. But now, if the watch arrested Lucas, Gasparo would take his revenge through the law. By all accounts, he was vindictive enough to demand the extreme penalty for this offense, when the offender could not pay substantial compensation: loss of a hand and both eyes.

Even if the judge mitigated the sentence, Venice would be no place for Lucas the half-Greek.

But where, then?

He began to swim, quickly and softly. After he turned off along an intersecting canal, the window and Moreta were lost to him.

It became very still. Few people were ever abroad after dark. He passed a number of moored gondolas, but their poles were stored indoors. Anyhow, a naked youth had best travel inconspicuously. Seeing the mouth of an alley gaping just beyond a ladder, Lucas climbed up and slipped into its concealing darkness.

The air chilled his wet skin. He shivered, fought against a sneeze, and wondered with increasing desperation what to do. Sunrise would trap him as certainly as the men of the Signori di Notte. He had disreputable friends, here and there--no, he thought, not such good friends that they’d help one who was hunted. Especially if Gasparo Reni offered a reward.

His throat tightened and tears stung his eyes. O all you saints, he protested, why did you have to let this happen? What am I to do?

Bad enough being damned to dreariness here, among aliens, with no other prospect for my whole lifetime; but now this!

A thought struck home. Terror, loneliness, self-pity scattered. By Heaven, he realized, this may be the very chance I’ve prayed for!

He laughed aloud, and hurried from shadow to shadow, across the city to the waterfront.

But at the Sclavonian Bank, he had to worm his way across the docks. Often he stopped, his heart almost bursting through his rib-cage at the sound of footsteps. When he reached shelter, his exhaustion was such that he could have gone no farther, though the watchmen’s pikes were to lift above him.

He cradled his cheek on an arm. Sleep came like a thunderclap.

A racket of shoes and voices, in the first vague light before dawn, awoke him. He tensed, instantly alert. Thank Heaven for youth, he thought in a wry corner of his mind; one needs the toughness to survive the consequences of the rashness. He was, in fact, only fifteen years old, of medium height but close-knit, well muscled for his age. His head was round, his face broad, with a freckled snub nose, high cheekbones and a wide full mouth, hazel eyes set far apart, reddish-brown hair.

The new arrivals were longshoremen, come to finish the loading of a fleet. Lucas had known a convoy would leave today, with woolens, iron, and timber for Constantinople. He knew every ship in harbor, where it was from and where it was going and when and with what. The knowledge had fueled all his dreams, while he toiled in Gasparo Reni’s countinghouse. He waited for his chance. Simply stowing away was not likely to get him far. But something might turn up.

His hiding place was in a stack of marble pieces, looted from Eastern cities and awaiting the day that some new building required them. A fluted column was hard against his hip, a frieze of centaurs like a barricade before him. Past the warehouses, he could see the twin spires of the Palazzo delle due Torri, near the Doge’s palace, and the top of the Campanile. All was dim and blue-black, under dying stars.

An opportunity came, sooner than expected. The laborers were busy stowing deck cargo, but not far from Lucas another man went up and down a gangplank, carrying personal baggage that he had fetched in a gondola. Obviously he was some passenger’s servant. Yet his cheap brown mantle, of Venetian cut, and the general look of him, suggested he was no beloved old retainer but merely hired for this occasion. He seemed worth testing; if inquiry gave negative results, well, something else must be tried. Lucas waited catwise. The man stooped to pick up a bag of provisions, such as all passengers must carry for themselves--at an instant when the stevedore gang was preoccupied with several ships down the line.

“Hsst!” called Lucas. “You, there!”

“What?” The man straightened and approached. Seen closer, he was a scrawny one. Indeed, thought Lucas, feverishly excited, the saints are being most helpful.

He kept his tones low and cool. “Would you like a bit of sport, Messer?”

“What’s going on? Where are you?”

“I have a sister. Young. Breasts like the dome of St. Mark’s.”

The stranger paused, a few feet away. Lucas raised his head over the marble blocks, grinning, and saw lechery. “This is no time or place,” the man hesitated. “Against the law.”

“True. But we’ve instant need of money, she and I, and there’s too much competition in the regular quarter. Only two grossi, Messer, the tenth part of a ducat, for as warm a half-hour as you’ll spend this side of Purgatory. And a good deal more pleasant, eh?”

“My work--”

“You’ve little left to do, I can see. Who’s your master?”

“A knight of Aragon.” The servant preened himself. “He engaged me out of a hundred others, to accompany him to Constantinople and back. I have to make this place ready.”

“You’ll be at sea for weeks, then. Perhaps a whole month. Heat, seasickness, crowding--”

“No, he’s engaged a room in the deckhouse. He’s too well-born to mix with common merchants and that ilk, sleeping in the open. I can spread my pallet at his threshold.”

“--bad food, worse water, and wine turned sour. Hardest of all, uninterrupted chastity. You might even perish at sea. Then think of my sister, as you gurgle down to the bottom!”

“Two grossi is too much.”

“Well, we can discuss that. Here, where no busybody watchman can spy us.”

The man came around the barricade, in among the marbles, and saw Lucas naked. His mouth fell open. Before he could cry out, he was attacked.

Lucas whipped him around, threw an arm about his neck, put a knee in the small of his back, and rapped sharply with the other hand. The man gasped once, and sagged. Lucas eased him down and undressed him. It was hard, acrobatic work in this cramped space, with the ever-present fear of discovery. His victim stirred and groaned. Lucas ripped a hem with the aid of his teeth, tore strips from the shirt, bound and gagged the man. Then he tucked him, helplessly squirming, in an entablature. Hastily he donned the remaining garments.

“You can get loose before sundown, I’m sure,” he said kindly. “I shall offer prayers for your welfare.”

He went out to the piled baggage and began loading it himself.

All the galleys of this convoy were identical, as Venetian law required: high in poop and forecastle, low in the waist, with oars and a single lateen-sailed mast. Catapults were mounted for defense against pirates; a shelter stood amidships for officers and the most important passengers. Lucas soon found the knight’s cubbyhole, the goods already there marked with the same emblem as those on the baggage he carried. He worked fast to get everything stowed before anyone paid attention to him. When at last he could close the door, he was all atremble. He unshuttered the little port, hoping the dawn air would clear his head. Now, more than ever, he needed nerve and wits.

If his gamble failed . . . best not think of that. Think what success would mean--a way opened to the fabled lands of his most gorgeous hopes!

Deck passengers bustled aboard. Sailors followed. Flags were hoisted, to flap brilliant in the sky above the vividly striped hulls. One by one, the galleys warped from the long quay. When all were clear, trumpets blew and oars rattled forth. They struck the water with an enormous noise, but fell at once into a steady creak-splash-thud as drums set their time. The ships formed convoy and stood out toward the Adriatic Sea.

Lucas watched from the cabin. He caught a final glare, where sunlight crashed on the great bronze horses atop the cathedral. Far northward, the mountains made a wan blueness. When the fleet neared the Lido, he discerned other craft, not only fisher boats but merchantmen which had lain at anchor until sunrise made entrance possible. They bore to Venice the goods of a hundred lands: from her own possessions in Dalmatia, the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea; from foreign countries from Iceland to Cathay. Saracen trade came here, despite all prohibitions of the Church. Even the hated Genoese came, though it did not seem that the uneasy peace between them and Venice could last much longer.

And I, thought Lucas with a leaping in his breast, am outbound.

The door opened. He whirled about.

The man who stood there was tall, and increased his height by soldierly erectness. His face was narrow, with a jutting beak of nose, gray eyes, thin lips framed by a pointed beard and mustaches. His black hair was cut short immediately below the ears, like most men’s. His doublet and hose were likewise black, of rich material, but he wore a white blouse and red cloak.