Rome: An Empire's Story (23 page)

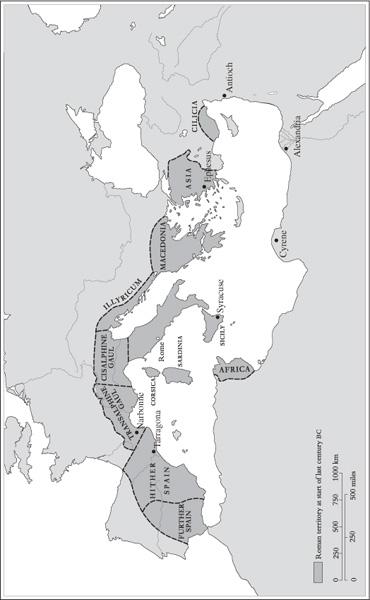

Map 3.

The Republican empire around 100

BC

KEY DATES IN CHAPTER IX

89–85 | First Mithridatic war, ending in the Treaty of Dardanus. Further wars with Rome followed in 83–81, and again in 73 |

88 | Sulla marches on Rome rather than give up the command against Mithridates to Marius, initiates a reign of terror, and then marches east |

86 | Marius and his ally Cinna become consuls after recapturing Rome. Widespread political violence. Death of Marius |

84 | Sulla returns from the east to depose his enemies who had established themselves in his absence, and to make himself dictator. Imposes political reforms on Rome, resigns dictatorship, and dies in 79 |

73–71 | Spartacus leads a slave revolt, which engulfed central, southern, and eventually part of north Italy until Crassus defeated him in southern Italy |

70 | The consulship of Pompey and Crassus. The trial of Verres for corruption as governor of Sicily establishes Cicero’s reputation |

67 | The |

66–62 | Pompey replaces Lucullus in the war against Mithridates, and then campaigns in Armenia, Syria, and Palestine, reorganizing Roman provinces and client kingdoms across the entire region |

63 | Cicero’s consulship, the conspiracy of Catiline, Julius Caesar elected |

62 | Pompey returns from the east and lays down his command but the Senate is slow to ratify his settlements or provide land for his veterans |

60 | Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar form a pact to pool their financial resources and political influence |

59 | Caesar consul. Then campaigns between 58 and 53 in Gaul, with raids into southern Britain and Germany |

53 | Death of Crassus following his defeat by the Parthians in the battle of Carrhae |

49–48 | Civil war between Pompey and Caesar ends with Pompey’s defeat at Pharsalus and murder in Egypt. Caesar becomes dictator |

44 | Caesar murdered on Ides of March by a conspiracy of senators, led by Brutus |

43 | Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian form a pact, and eliminate their political enemies, including Cicero |

42 | Mark Antony and Octavian defeat Brutus and Cassius, ‘the Liberators’, at the battle of Philippi |

31 | Octavian defeats Antony and Cleopatra, ending civil wars |

IX

THE GENERALS

His monument is on the field of Mars, and inscribed on it an epitaph which he is said to have composed himself. The substance is that none of his friends outdid him in kindness, nor any of his enemies did him more harm than they received in return.

(Plutarch,

Life of Sulla

38.4)

Deadly Rivals

Sulla’s epitaph is a chilling memorial to the horrors of politics at the end of the Republic. Friendship and enmity were both competitions, and Sulla had won on both accounts. He died owing no debts of gratitude, and leaving none of his rivals unpunished. Perhaps this was a traditional aspiration, but the scale of Sulla’s realization of it was truly terrifying.

Sulla had served under Marius in the war against Jugurtha and had pulled off a political coup by having the Numidian prince betrayed into his, rather than into Marius’, hands in 107

BC

. That compounded a rivalry based on their opposing political positions. Marius, the new man, was the champion of the people, while aristocratic Sulla was better liked by the nobility. He continued to distinguish himself as a general in the wars against the Germans, on an eastern command in Anatolia, and then again in the Social War against

the Italians. Elected consul for 88

BC

, he was the obvious man to be given the command against Mithridates, and so he was. But then civil conflict made another of its lethal intersections with Roman imperialism. A tribune named Sulpicius Rufus passed a law transferring the command to Marius. That was a scandal, but one that was dwarfed by what Sulla did next. Refusing to accept the decision, he marched his soldiers into the city, had Sulpicius killed, and drove Marius into exile. Master of Rome, he compelled the Senate to pass his own legislation, including reassigning the eastern command to him. Sulla then marched east to Macedonia, rapidly put Mithridates’ generals on the defensive, and laid siege to Athens. He was as implacable there as in Rome: the Athenian

agora

, its ancient marketplace, was awash with blood. The story goes that Sulla only agreed to stop the massacre because of his love of classical Greek culture, saying that he spared the few for the sake of the many, the living for the sake of the dead. Then he pressed on to Asia to make a shameful peace with Mithridates at Dardanus. The king was granted his lands, recognized as a Roman ally once again, and effectively forgiven his crimes in Asia in return for supporting Sulla. For Sulla was keen to return. In his absence he had been outlawed, and his enemies Cinna and Marius had seized control of the city, waging their own reign of terror. Perhaps fortunately both were dead before Sulla got back home. His army invaded Italy in 84 and he soon seized the city. There he had himself made dictator and issued a list of his enemies, many of them associated with the

popularis

movement and friends of Marius. Those proscribed on the list could be killed with impunity and lost their property: in a cunning move it was auctioned off at knock-down prices, thereby implicating the buyers in Sulla’s coup. A few of the proscribed were killed, others—including the young Julius Caesar—fled for their lives. Sulla then used his dictatorship to impose his own political solution in a series of laws that in some ways resembled those proposed by Drusus just before the Social War. There would be a larger Senate (so recruiting the most prominent of the equestrians and ending the rift between the two orders engineered by the Gracchi); the tribunes were stripped of most of their powers, making it much more difficult for

popularis

politicians to use the assemblies to outflank the Senate (as the Gracchi, Saturninus, and Sulpicius Rufus had done); the Senate would control the courts, freeing governors from the need to kowtow to equestrian juries; and senatorial careers were to subjected to a stricter discipline with minimum ages for the senior magistracies. Sulla also distributed land to his soldiers, imposing colonies on many Italian cities: Pompeii was among those chosen and we can follow in detail the uneasy coexistence of ancient Oscan families and Sullan veterans in the politics of the city over the next few decades. Then Sulla surprised everyone once again, by resigning the dictatorship in 80. The next year he died in retirement of natural causes.

1

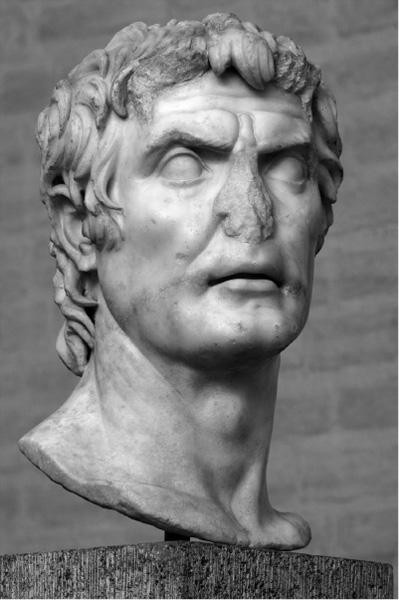

Fig 9.

Bust of Sulla in the Munich Glyptothek

Sulla left a grim legacy. It was not so much the constitutional laws, which were broken and abolished during the 70s with no power to protect them, or the administrative reforms, which were uncontroversial. But the example he set was a terrifying one. Sulla was the first general to attack Rome with

a Roman army. Sulla made the dictatorship (originally an emergency measure designed for moments when the city was in peril) into a tool for suspending civil society. Sulla invented proscription. His violence and the feuds it stirred up haunted Rome for a generation. When Pompey won his victories in the east in the 60s, it was widely feared he would return ‘like Sulla’. Julius Caesar made himself dictator in the 40s. Octavian and Antony issued their own proscriptions. And politics had become incurably partisan. Perhaps the Gracchi had been idealists, and maybe Drusus had genuinely thought he had a solution to the Italian question. After Sulla, Roman politics got personal.

Sulla was not the first, or the last, reformer to forget that the act of changing the constitution sets a precedent for future changes, even if it is intended to bring harmony and stability. A number of his innovations were sensible, such as increasing the number of praetorships to provide enough magistrates and ex-magistrates to govern Rome’s growing empire. Others, like increasing the size of the Senate, were pragmatic, especially given all the potential new recruits from the enfranchised Italian cities. But his solution did not tackle the conditions that made his rivalry with Marius possible. Personal rivalry was old as Rome. The tomb of the Scipiones shows the high value placed on individual achievement as well as on the name of the greatest families.

2

From Cato the Elder to late antiquity we can hear aristocrats singing the praise of great figures of the past while condemning the vices of their rivals. Cicero and Sallust occasionally imagined that before the tribunates of the Gracchi the virtues of individuals like Scipio Aemilianus had been harnessed to the common cause. Livy celebrated mythical acts of heroic self-sacrifice in the early days of the Republic.

But the lethal innovation of the last century

BC

was the involvement of the army. Marius had very nearly deployed his veterans in support of his

popularis

allies, but in the end it was Sulla who took the first step. The close bonds formed between Marius and Sulla and their veterans were not purely sentimental, nor even a recognition of the great quantities of booty that might be won in some campaigns. The increased recruitment of citizens without land made them depend on their generals for resettlement: Sulla’s army marched against Rome on the first occasion because they wanted eastern booty, and on the second in order to win land. He did not disappoint them. Why would future Roman armies not do the same as they had? None of Sulla’s reforms touched this problem. Augustus would solve it by creating a military treasury with hypothecated revenue to pay fixed

discharge bonuses to the veterans of what had become a standing army, one bound to the emperors by ritual and ideology as well as self-interest. No solution of that kind was, as far as we know, ever discussed during the Republic. Romans still could not conceive of an alternative to a citizen army commanded by an aristocratic general. Besides, Sulla’s own career had established a model of the kind of behaviour he tried to outlaw, one that would be imitated by his lieutenants, including Lucullus, Crassus, and Pompey, and his enemies, especially Caesar. The failure of his constitutional solution within a decade of his death in 79 showed the power of the competitive urges he tried to stem. During the 70s the next generation of generals, most of them Sullan protégés, waged ferocious wars around the Mediterranean. Their opponents were very various. Pompey hunted down Marian survivors first in Africa in 82–81 and then in Spain in 77–71; Crassus waged war on Spartacus’ slave rebellion in 72–71; Marcus Antonius and Quintus Caecilius Metellus both took the name Creticus for their campaigns against pirate strongholds on Crete in 71 and 69–67; while Sulla’s oldest deputy, Lucullus, won the prized command against Mithridates. Every kind of campaign strengthened the bonds between generals and their armies, making renewed civil war ever more likely.