Roosevelt (2 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

The President reading the joint resolution by both houses of Congress declaring that a state of war exists with Germany and Italy, December 11, 1941

Hitler and Mussolini conferring in 1941

Emperor Hirohito of Japan

Joint press conference with Winston Churchill, Washington, D.C., December 23, 1941

Roosevelt’s “secret” war-plant inspection tour: Addressing workers at the Oregon

Shipbuilding Corporation, September 23, 1942. Henry J. Kaiser is in the back seat. Inspecting bomber production at the Douglas Aircraft Corporation, Long Beach, California, September 25, 1942

John Nance Garner visiting Roosevelt aboard the President’s inspection-tour train, Uvalde, Texas, September 27, 1942

Lunch in the field: Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, President Roosevelt, Harry Hopkins, Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., Rabat, Morocco, January 21, 1943

Forced handshake: Generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle with Roosevelt and Churchill, Casablanca, January 24, 1943

United States and British military leaders discussing strategy at Casablanca: Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations; Gen. George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff; Lt. Gen. H. H. Arnold, Air Force Chief; Brig. Gen. John R. Deane, U.S. member of secretariat; Brig. Vivian Dykes, British member of secretariat; Brig. Gen. A. C. Wedemeyer, member of War Plans Division; Lt. Gen. Hastings L. Ismay, Chief Staff Officer to Minister of Defence; Vice Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten, Director of Combined Operations; Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, First Sea Lord; Gen. Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff; Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff; and Field Marshal Sir John Dill, chief of the British Mission, Washington

Roosevelt, en route home from Casablanca, celebrating his 61st birthday aloft, with Adm. William D. Leahy, Harry Hopkins, and Capt. Howard M. Cone, commander of the Boeing Clipper January 30, 1943

The President with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang, at the Cairo Conference, November 25, 1943

Roosevelt, on the way to the Teheran Conference, in Sicily with Gen. Dwight

D. Eisenhower, December 8, 1943

At the Teheran Conference: Harry Hopkins, Stalin’s translator, Marshal Stalin,

Vyacheslav Molotov, K. Y. Voroshilov

Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Senator James F. Byrnes, and Senator Alben W. Barkley welcome Roosevelt back from Teheran, Washington, D.C., December 17, 1943

Pacific strategy conference, Honolulu: the President with Gen. Douglas Mac-Arthur and Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, July 27, 1944

Judge Samuel I. Rosenman and Lt. Comm. Howard G. Bruenn, Medical Corps, U.S. Navy, during the President’s Hawaiian trip, July 1944

Americans of Polish descent calling on the President at the White House, Pulaski Day, October 11, 1944

President and Mrs. Roosevelt on the campaign trail, New York City, October 21, 1944

Roosevelt after addressing the Foreign Policy Association, with William H. Lancaster, Association Chairman; Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson; Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal; UNRRA Director General Herbert H. Lehman, New York City, October 21, 1944

Roosevelt with Fala, at Hyde Park, October 22, 1944

Campaign banner in his political homeland floating above the President’s car, Newburgh, N.Y., November 6, 1944

Roosevelt campaigning with Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., near Hyde Park, N.Y., November 6, 1944

The President, after re-election to a fourth term, with Vice President-elect Harry S Truman and Vice President Henry A. Wallace, making a brief radio address on his arrival in Washington, November 10, 1944

Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd. Painting by Elizabeth Shoumatoff

The President and Mrs. Roosevelt with their thirteen grandchildren, in the White House, January 20, 1945

The first day of the Big Three meetings at Yalta, February 1945

Roosevelt making a point to Churchill at Yalta

The President reporting to the Congress on the Yalta Conference, March 1, 1945

Roosevelt with the United States delegation to the United Nations founding conference at San Francisco: Rep. Sol Bloom, of New York; Virginia Gilder-sleeve, Dean of Barnard College; Sen. Tom Connally, of Texas; Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Jr.; Harold Stassen; Sen. Arthur H. Vandenberg, of Michigan, and Rep. Charles Eaton, of New Jersey, at the White House, March 1945

The caisson bearing President Roosevelt’s coffin approaching the Capitol on the way from Union Station to the White House, April 14, 1945

Fall 1940

T

HE GLEAMING LIGHTS OF

the house shone against the dark that enveloped the south lawn and the woods and the Hudson below. Inside, a host of family and friends celebrated over scrambled eggs as the final clinching returns came in through the chattering teletype machines. The President sat with a small group in the dining room, his coat off and his necktie loosened, tally sheets spread out before him. It was election night, November 5, 1940.

Toward midnight the guests rushed to the windows at the sound of a commotion outside. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s neighbors were straggling down the entrance road and mustering in a singing, jostling crowd before the portico. Their torches threw dancing tongues of red light onto the ancient trees, the thick hemlock hedge around the rose garden, the long white balustrade. A drum-and-bugle corps blared out victory tunes. An exuberant banner proclaimed

SAFE ON THIRD.

A door opened. Franklin Roosevelt moved haltingly to the balustrade. He leaned on a son’s arm, his face full and ruddy in the glow of the cameramen’s flares. Arrayed with him were his mother, Sara, his wife, Eleanor, his sons Franklin and John and their wives. At the rear of the portico, standing alone, his face exultant, Harry Hopkins smacked his fist into his palm as he performed a little pirouette of triumph. Out front a boy darted forward with a placard on which the words

SAFE ON THIRD

had been clearly printed over

OUT STEALING THIRD,

and the President laughed with the crowd.

It was a moment of enormous relief for Roosevelt. Earlier in the evening he had been upset by early election returns from New York; but far more important, he had been worried for weeks about the ominous forces that seemed to be lining up with the opposition. There were altogether too many people, he felt, who thought in terms of appeasement of Hitler—honest views, most of them, he granted, but views rising out of materialism and selfishness. Vague reports had come in of obscure fifth-column activities.

Speaking to Joseph Lash that election night, Roosevelt was blunt: “We seem to have averted a

Putsch,

Joe.”

But now, standing before the crowd, Roosevelt could forget the stress of the campaign. He joked with his neighbors and reminisced about this “surprise” celebration—actually an old election-night tradition at Hyde Park.

“A few old greybeards like me,” he said, “go back to 1912 and 1910. But I think that, except for a very few people in Hyde Park, I go back even further than that. I claim to remember—but the family say that I do not—and that was the first election of Grover Cleveland in 1884.

“I was one and a half years old at that time, and I remember the torchlight parade that came down here that night….

“And this youngster here, Franklin Roosevelt, Jr., was just saying to me that he wondered whether Franklin, 3rd, who is up there in that room, will also remember tonight. He also is one and a half years old….

“We are facing difficult days in this country, but I think you will find me in the future just the same Franklin Roosevelt you have known a great many years.

“My heart has always been here. It always will be.”

“The same Franklin Roosevelt you have known …” A few in the crowd must have remembered Franklin as a small boy snowshoeing across the fields, shooting birds for his collection, skating and ice-boating on the Hudson. Then Hyde Park had not seen much of him for a time. Fall after fall he had left for school—for four years at Groton and for another four at Harvard.

He had returned to settle down with his widowed mother, but not for long; soon he made a suitable marriage with his distant cousin Eleanor Roosevelt, a niece of President Theodore Roosevelt. Again he had left Hyde Park—this time for Manhattan, where he studied and practiced law. Hyde Park had seen a good deal of him in the fall of 1910 when he campaigned strenuously to capture a seat in the New York Senate. But then he was off again—to Albany, where he spent two years as an anti-Tammany Democrat; to Washington, where he served Woodrow Wilson as Assistant Secretary of the Navy; to the political crossroads of the nation, as he campaigned in 1920 for the vice presidency.

Then suddenly he was home again, his body seemingly shrunken, his long legs inert, his political career in ruins. For seven years he had searched for a cure for the effects of infantile paralysis, resting at Hyde Park, crawling around lonely beaches in Florida,

swimming in the buoyant waters of Warm Springs, in Georgia. He never found the cure. But he had found himself, steadied his political course, struck out for the highest stakes in the nation’s politics. In 1928 his neighbors had helped send him to Albany, where he governed New York for four years. In March 1933 he had left Hyde Park for Washington, amid a numbing depression, to preside exuberantly for eight years over a nation in upheaval and regeneration.

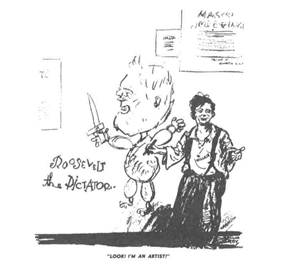

September 18, 1940, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York Post

And then 1940. He had broken tradition to win a third-term nomination, taken on a formidable adversary in Wendell Willkie, and plunged into the maelstrom of shifting political alliances and seething political reactions to events abroad. He had faced isolationists in both parties, a labor turncoat in John L. Lewis, a bleak parting with his old campaign manager, James A. Farley. Hitler dominated events in America. The presidential politician who above all had sought to keep his choices wide and his timing under control had had, at the height of the campaign, to send destroyers to England and to draft American boys.

October 14, 1940, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York

Post

The pursuit of victory had exacted a heavy price. In the last desperate days, Roosevelt had made some fearsome concessions to the isolationists. After Willkie hurled the flat prediction that a third term would mean dictatorship and war, Roosevelt had assured the “mothers of America” categorically that “your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” Yet his whole posture toward Hitler for months had been founded on the assumption that fascism was a menace to democracy everywhere, that the Nazis would not be content with the conquest of Europe but, with their junior partners, Italy and Japan, would ultimately carve up the world. Still, there was this flat pledge to the mothers of America.

And now he was back, at the height of his power and prestige. Who was this Franklin Roosevelt? The master campaigner who had evaded the Republican attack and then outflanked and beaten his enemies in the last two weeks of the campaign? The son of Hyde Park who had never really left home, who had measured men and events by old-fashioned standards of

noblesse oblige,

aristocratic responsibility, inconspicuous consumption? The graduate of

Groton who was still inspired by Rector Endicott Peabody’s admonitions about honesty, public morality, fair play? The state legislator who had embraced an almost radical farm-laborism at the height of Bull Moose reform? The Democratic-coalition politician who had learned to barter and compromise with Tammany chiefs, union leaders, city bosses, Western agrarians, Republican moderates, and isolationist Senators? The Wilson internationalist who had fought for the League of Nations but then abandoned it? The humanitarian who could spend billions for relief and recovery but almost obsessively preach the need for a balanced budget? The foe of totalitarianism who had stood by, vocal but inactive, during the agony of Munich? Could he be all these things?

No one—certainly not his Hyde Park neighbors—could have answered such questions this election night of 1940. They might have seen some significance, however, in the people gathered around Roosevelt on that mild November evening.