Roosevelt (42 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

In the White House, Roosevelt was talking with Secretary of War Dern when a secretary came in with the bad news on a slip of paper and laid it before him. Eager reporters crowded around Dern afterward: How had the President reacted to the news? “He just held the sheet of paper in front of him,” said Dern, “and smiled.” The smile was significant. To this decision Roosevelt would

enter no dissenting opinion, no “horse-and-buggy” remark. The situation had gone far beyond such talk. More than any other previous decision, Attorney General Robert H. Jackson later remembered, the

Butler

case had turned the thoughts of men in the administration toward the impending necessity of a challenge to the Court. Roosevelt’s smile was that of a fighter ready for the struggle ahead, perhaps too of a tactician watching his opponent overextend himself.

“It is plain to see,” wrote Ickes in his diary after a cabinet meeting later in the month, “from what the President said today and has said on other occasions, that he is not at all averse to the Supreme Court declaring one New Deal statute after another unconstitutional. I think he believes that the Court will find itself pretty far out on a limb before it is through with it and that a real issue will be joined on which we can go to the country. For my part, I hope so.”

If such was Roosevelt’s tactic, the Supreme Court walked straight into the trap. There was a lull when the TVA won validation of its right to sell power generated at Wilson Dam, with only McReynolds dissenting. But on May 18 the work of demolition was resumed. In

Carter

v.

Carter Coal Co.

Hughes sided with Roberts and the rightists in ruling invalid the labor provisions of the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1936. A week later the Court in another 5-4 split voided the Municipal Bankruptcy Act on the ground that it infringed on the rights of states to deal with their municipalities.

The climax came on June 1, 1936. With the national conventions only a few weeks off, the Court took a step that was bound to plunge it into the political turbulence of the year. By another 5-4 decision it invalidated the New York minimum wage law—and in effect those of other states as well. Probably more than any other action, concluded a historian of the Court, this decision “revealed the grim and fantastic determination of the narrow Court majority to preclude legislative intervention in economic and social affairs.” For all its fine words about the reserved powers of the states, the Court seemed to be as much against state New Deals as it was against the national one. In a ringing dissent Stone warned that a legislature must have necessary economic powers or government would be rendered impotent. Privately Hughes was deeply troubled by the excesses of the “steady four.”

Roosevelt put his finger on the crucial consequence of the decision. The Court, he said, was creating a “no-man’s-land” where neither state nor federal government could function.

“How can you meet that situation?” a reporter asked.

“I think that is about all there is to say on it,” Roosevelt replied. The President would not tip his hand—yet.

Another result of the Court’s actions was to make necessary a fuller legislative program than the President originally had planned. The Court’s upset of the AAA left Congress floundering until Wallace and farm organization leaders worked out a method of crop control through an expansion of the Soil Conservation Act of 1935. After the AAA’s derailing denied the government half a billion in processing taxes, the President, without consulting even the House Ways and Means Committee, sent specific instructions on a new tax program. Swallowing their pride, congressmen voted for those features most palatable in an election year—a graduated tax on undivided profits and on all corporate income, and a “windfall” tax aimed at those processors who had profited as a result of the

Butler

decision. A legislative item left over from the second Hundred Days and from the vacuum created by the NRA overthrow was the Walsh-Healey bill regulating labor standards of firms receiving government contracts.

On other matters the President held the presidential reins over Congress rather loosely. A conspicuous example was the veterans’ bonus bill. The year before, Roosevelt had vetoed the bill in a brilliant message that he had delivered orally to Congress, and Congress had sustained him by a hair. This year the congressmen were scrambling for their cyclone cellars, fearful of veterans’ wrath in November. Recognizing their plight, Roosevelt forsook his valiant role of yesteryear and sent Congress a feeble note indicating that he had not changed his mind. Congress passed the bill over presidential veto. What was good election politics for the President was evidently not good election politics for congressmen. By this method of playing both ends against the middle, both the President and his cohorts could live to fight another day.

A final consequence of the judicial demolition was further to confirm Roosevelt in his leftward direction. After years of wobbling back and forth along a middle way, the President was now committed to a militant if still somewhat ambiguous and limited progressivism. And this development raised the whole question of Roosevelt’s relationship to the American right.

For months a vast bitterness against the President had been welling up from what Ickes later would call the grass roots of every country club in America. This bitterness varied in tone from the august denunciations of the Liberty League and the big business associations to the stories that went the rounds of club and bar. Some of these,

touching on the President’s egoism and compulsion to dominate, were genuinely funny, and no one laughed louder at them than did Roosevelt. Others were mean and smutty, told behind cupped hands in Pullman cars. Still others were simply fantastic, such as the widely circulated stories about maniacal laughter someone had heard from the President’s study in the White House, about doctors wheeling away a limp, gabbling figure.

Roosevelt could laugh at his right-wing foes. He roared at a story that George Earle brought him about four wealthy members of Philadelphia’s exclusive Rittenhouse Club who were sitting in the library late in 1935 sipping drinks and damning the President and all his works. After a while one of them happened to turn on the mahogany-encased radio. Suddenly a well-known voice came out referring scornfully to criticisms of the New Deal by “gentlemen in well-warmed and well-stocked clubs.” It was Roosevelt, making a speech in Atlanta.

“My God!” exclaimed one of the men, according to Earle’s story, “do you suppose that blankety blank could have overheard us?”

But the President was also confused and hurt by the rancor from the right. He had not sought it. Had he not saved the capitalistic system? It was with political guile but also in real perplexity that later in the year he told his fable:

“In the summer of 1933, a nice old gentleman wearing a silk hat fell off the end of a pier. He was unable to swim. A friend ran down the pier, dived overboard and pulled him out; but the silk hat floated off with the tide. After the old gentleman had been revived, he was effusive in his thanks. He praised his friend for saving his life. Today, three years later, the old gentleman is berating his friend because the silk hat was lost.”

What had happened? It has often been said that Roosevelt betrayed his class, historian Richard Hofstadter has noted, “but if by his class one means the whole policy-making, power-wielding stratum, it would be just as true to say that his class betrayed him.” If so, how can this be explained?

The mystery deepens when Roosevelt is viewed less in his familiar posture as a liberal or progressive, and more as a conservative acting in the great British conservative tradition. That tradition has its cloudy and contradictory aspects, but certain of its elements have shown a tenacity and continuity down through the years. They are: the organic view of society, compelling a national and social responsibility that overrides immediate class or group interest; a belief in the unity of the past, the present, and the future, and hence in the responsibility of one generation to another; a sense of the unknowable, involving a respect for the limits of man’s knowledge and for traditional forms of religious worship; a

recognition of the importance of personal property as forming a foundation for stable human relationships; personal qualities of gentility, or gentlemanliness, that renounce vulgarity and conspicuous display and demand sensitivity to other persons’ needs and expectations; and an understanding of the fact that while not all change is reform, stability is not immobility.

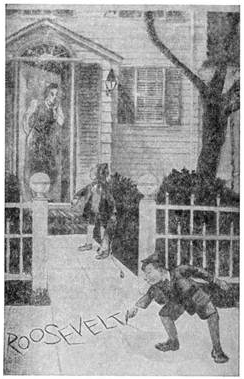

“MOTHER, WILFRED WROTE A BAD WORD!”, Dorothy McKay, reprinted from

Esquire,

November, 1938, copyright by

Esquire,

Inc., 1938

If such are some of the chief lineaments of an enduring conservatism, Roosevelt seems to have been a conservative by many tests.

During his first two years in office Roosevelt could hardly have displayed more loyalty to the conservative belief in the need for an abiding devotion to some national or general interest that transcended party, or group, or sectional concerns. He called for a national effort against economic crisis; he played down the role of party and partisanship. He proclaimed the need for a true concert of interests, and the NRA, as he visualized it, was simply the institutionalization of that idea. He was leader of all the people, and he was perfectly willing to subordinate the interests of his class to his idea of the national interest at the same time that all other interests found an equal place in the national plan.

A belief in the unity of past, present, and future? This central concept of Edmund Burke was a root principle in Roosevelt. It revealed itself in his absorbing concern for his ancestors, for Dutchess County history, for local customs and traditions; in his lifelong interest in tree farming; in his solicitous concern for the national heritage, however vaguely he conceived it, that was passing through one generation of Americans after another. Probably the most persistent interest he had in public policy involved conservation of natural and human resources.

Roosevelt was a religious man—“a very simple Christian,” his wife once called him. He was christened in St. James Episcopal Church in Hyde Park, became a vestryman there in 1928, and later the senior warden, as his father had been before him. He liked the hymns and Psalms, the order and routine of the church. The intensity of his religious feeling is not easy to gauge; certainly there was a strong conventional element, and church attendance for him was at least as much a politically and symbolically important ritual as it was an opportunity for communion. He was unconcerned about religion as a philosophy, although toward the end of his life he became interested in Kierkegaard.

A belief in personal property? Roosevelt, like most other leaders of property-hungry masses through American history, wanted not the suppression of property but its broader distribution. He believed in the family-sized farm—the farm that a man and his wife and his sons could live on. He believed in enabling workers to own their houses; he experimented long and hard with resettlement

projects that gave people a chance to maintain their own houses and till their own plots. To Roosevelt there was a difference not in degree but in kind between this type of property owning and corporate ownership. A prudent householder himself, he handled his own property with affection and circumspection.

Roosevelt was a gentleman in all but the prissy sense of the term. “He was decent; he was civilized; he was kind,” Gunther wrote. He disdained coarseness or vulgarity; he never used more than the milder, more conventional forms of profanity; he avoided excessive show of feeling and expected other people to; he expected people to have good manners; he hated the kind of ostentation that he had seen in fashionable centers. His consummate ability to identify his own feelings with other people’s was, of course, an essential part of his political technique. He had a continuing sense of responsibility for the health and well-being of his staff and of other people around him.

Roosevelt’s attitude toward change cannot be so simply set forth. He had a love for innovation and experimentation in government that clashed with the conservative’s repugnance for unnecessary change; at the same time, he had a curious instinct for fixity in his personal affairs, such as the arrangements in his bedroom and office; and his tenderness for Hyde Park rested in part on his sense that here was a point of stability in a relentlessly changing world. To the extent that he thought about the implications of governmental change, moreover, Roosevelt defended change as essential to holding on to the values of lasting importance. For over a century conservatives in Britain had been demonstrating, through such reforms as factory acts and social welfare services, that minor changes in institutions and laws were necessary to conserve enduring ends. And in this sense, too, Roosevelt was a conservative.

The argument should not, of course, be overstated. Roosevelt was too much of an opportunist and pragmatist to be catalogued neatly under any doctrinal tradition, no matter how broad it might be. Moreover, he did not believe in such conservative ideas as the need for hierarchy in society, the natural inequality of man, and the pessimistic view of man and his potentialities. His mind, open to almost any idea and absolutely committed to almost none, welcomed liberal and radical notions as well as conservative. But if any balance could be drawn, he was far closer to the conservative tradition than any other. He could say—and did say—with the great conservatives: “Reform if you would preserve.”