Rosie's War (22 page)

Authors: Rosemary Say

‘Wait a sec,’ she said. We could vaguely make out her figure as she felt her way around. We heard something shift. ‘Watch out. There’s coal everywhere.’

We hadn’t asked ourselves beforehand what a coal bunker was really like to spend the night in. Now we knew: there were mountains and valleys of the stuff. Frida went in and set off what seemed like an avalanche.

‘Damn, this stuff here’s coke not coal. It slides about if it’s even touched.’

The three of us found an empty bit of floor and sat down gingerly. We daren’t lean against the coal, for fear of setting it off. The floor was too dirty to lie on. So we had to sit bolt upright.

‘We’ve got ages ahead of us,’ Penelope whispered. ‘I don’t know if I can stay like this. The freezing cold will give us cramp.’

But there was no point in complaining – we were going to be here for about ten hours. Had the sentries heard the noise from the coal? We had to stay still and quiet all night. Somehow this didn’t seem the most heroic of escapes. I began to doze, fitfully waking up as I toppled over in my sleep.

‘Pat!’ Frida hissed. She pinched her nose. ‘You’re snoring.’

I looked at my watch. It was just gone eleven. I didn’t sleep or even doze again that night. I started to get awful cramp in my calves and did some foot-curling exercises to try to get some circulation going. My toes were numb. I started to worry about my cough. Shula had given me a packet of lozenges from the nuns’ pharmacy and I got through the whole lot. I survived the wait without a serious bout of coughing. In retrospect, I think that my worries about cramp and bronchitis helped me to get through the night. They certainly diverted my mind away from fear or boredom.

As dawn approached I was wide awake with my mind racing. This really was the beginning of my journey home. I could see my parents’ front door. I imagined myself walking up the road to Hampstead Heath. Just then I heard the sentries not far off. They were laughing and slapping their arms against their bodies to keep warm. Frida listened intently to hear what they were saying. Their voices faded away. She nodded.

This was our opportunity. We had been banking on the fact that they would go to the guardroom to have a drink and get warm. The handover to their replacements would probably take a few minutes. Frida moved cautiously. She stifled a yell of cramp pain and eased up to the window above her head. She groaned.

‘Damn! It’s all off,’ she whispered. ‘It’s been snowing. They’ll see our tracks leading from the hut.’

I couldn’t believe it. It was just our luck that the first snow of the year had fallen on our escape day. I was so exhausted after a night of sitting upright that I could hardly think. But I knew that this was our one chance. We had to go now.

I clambered up to the window and peered into the murky light. In fact there wasn’t much snow on the cinder track that led from the outhouse to the fence. So perhaps our footprints might not be seen after all.

I gently opened the window and climbed out. I ran the few yards to the fence. To my disbelief I found that the wire had been cut to allow the lorry through and then merely looped back in place. Presumably the driver had to make regular deliveries. He had probably thought that with the guardroom so near there was no risk of any prisoner escaping by this route. I was shaking with excitement as I returned to the window and told them what I had seen.

‘There’s hardly any snow on the path, so we can get to the fence without being noticed. There’ll be people walking on the road on the other side. Nobody will see our footprints. Let’s go.’

We said our goodbyes to Penelope. She squeezed my hand but said nothing. Frida scrambled out of the window and darted over to the fence. She turned to me and I ran to join her. I lifted up the cut fence to let her through. As I did, the edge of the wire I was holding got caught with the wire above. It looked as if it would hold to let me through. Frida waited on the other side of the wire, looking around anxiously. Just as I stepped through, the top wire released its hold and I felt the sharp jaws bite into my coat.

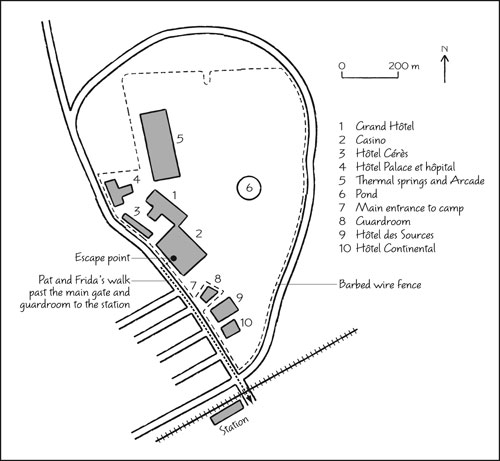

I was caught. Somehow I had known that this would happen. I froze. But Frida didn’t panic for one moment. She eased the prong out of my coat with her long, bony fingers. We heard the sounds of footsteps not far away. She pulled hastily, leaving a piece of coat on the wire. We crouched down. It was about six o’clock and the sky was lightening a little. In the distance a few early workers were stumbling along the snowy road in the direction of the town and the railway station. Frida carefully pulled the piece of my coat from the wire and looped the fence back. We jumped on to the road where the men had been walking. We looked back at the outhouse: a hand waved and the window closed.

So far so good, except for my damaged coat which might look a bit strange. We tightened our headscarves, picked up our few belongings and began to walk down the road. We could see the big gates of the main entrance on our left. We would have to walk straight past them. We kept our heads down. A bicycle silently passed us. It was a German soldier. I had a horrible vision of us stupidly being caught on our own doorstep and taken back to the camp. He turned down a side road.

We walked on without speaking. It seemed to me that we weren’t even moving. I heard someone call across the road to a friend. We were approaching the lighted guardroom at the main gates of the camp. The windows were steamed up. The soldiers inside were eating and drinking with much guffawing. One of them rubbed a clear spot on the window with his hand and peered out. I doubled up in a paroxysm of coughing. It was sheer nerves. Frida put her arm around my shoulder. We walked right by the front gates of our prison.

We reached the station after about ten minutes. We had agreed that I would do the talking wherever possible. Although Frida’s French was very good, it was I who could pass for a native. She was going to be our German speaker if (please God it didn’t happen) we needed to talk ourselves out of trouble. I bought two tickets for Besançon. The man in the office yawned and handed them to me with my change.

The Escape Route

‘You’ll need to get the connecting trains at Épinal and Nancy,’ he muttered without even looking up.

We walked on to the platform. To my horror the first person I saw was the German head doctor from the camp, standing a few yards away on my left. ‘Good God, Frida,’ I breathed. ‘I went to see him just last week. He’s the awful man who’s been treating me for bronchitis. You know, the one who told me that the Germans will be in Piccadilly before I leave this camp. Why did I try to persuade him that I should be sent home? He’s bound to remember me.’

‘No eye contact, that’s the secret,’ she whispered.

Worse was to follow. I nudged Frida in the ribs. The Kommandant’s secretary was deep in conversation further down the platform. She knew us well. We turned our backs to the tracks and gazed fixedly at the worn posters on the platform wall. Time seemed to stand still. Where was the train? We could hear people walking along the platform behind us. Was one of them the doctor? Or the secretary? The urge to turn round was almost irresistible. I stared as hard as I could at the poster advertising Vittel water. If I didn’t look at anyone, perhaps nobody would see me – the ostrich method of escape!

When the train finally arrived we moved quickly down to the other end of the platform. It was getting lighter all the time. We got into a small, closed compartment. The train slowly moved away from Vittel. We looked at each other, hardly breathing. We had done it. Until Épinal, at least.

We slunk off the train about an hour later, looking apprehensively at the disembarking passengers. There were none that we knew. We showed our tickets and walked into the town without speaking. We had the whole day to wait before our connection for Nancy. We felt an exhilarating freedom: for the first time in almost a year we were able simply to wander around a town, drinking in the life. The sounds and the smells were so strange. And the queues! Outside all the food shops were long lines of weary housewives, dressed in shabby clothes and holding huge baskets. It was only after perhaps an hour that we began to worry that the place was full of Germans in uniform, presumably on leave.

Two soldiers approached us. I clung to Frida’s arm, trying to hide my torn coat. The taller of the two took out a packet of cigarettes and offered one to me. He smiled broadly and said: ‘Promenade, Mademoiselle?’

I shook my head and held on to Frida even more tightly. We moved away.

‘Let’s get out of here,’ Frida said. ‘We’re too obvious. No one else is just walking these streets.’

She was right. There were no other civilians sauntering along looking at shops. We needed to get inside somewhere, away from people if possible. It was bitterly cold and had started to snow. By now we were feeling exhausted from the lack of sleep and the high nervous energy of the escape. We slipped into a small church down a side street and sat on the hard pews at the back. At that time of the morning it was totally deserted. Trying to look devout, we bent our heads and began to divide up our meagre portions of hard biscuits and cold potatoes. Within a few minutes the pews began to fill up for morning mass.

‘Don’t worry,’ I whispered to Frida. ‘I know all the forms of service from my sessions with the nuns.’

She didn’t look totally convinced. As a bell tinkled I nudged her to stand. She shot up, wiping the last crumbs from her coat. The rest of the congregation promptly knelt down. This was clearly no place for us. I started to cough violently. By sheer luck, I couldn’t have done anything better: I became just another person trying to cope with a consumptive cough in that cold church. We made our way out as unobtrusively as possible.

We were still faced with the problem of how to pass the hours before our connection to Nancy. We had to get off the streets. After a while we succumbed to a warm cafe in a bleak, lonely part of town. We made our cups of ersatz coffee last as long as we could, sitting opposite each other in an uneasy silence.

By five o’clock we were back at the station and soon installed in a cold and dark carriage which we had to ourselves. We were by now both very sleepy. Just as the train’s whistle was blowing, the door was flung open and three boisterous German soldiers piled in. Frida and I looked at each other, horror-struck. We quickly put our heads down and pretended to doze. All thoughts of a real sleep had vanished. They kept up a continual chatter. I could just see that one of them was staring at us and whispering to his friends. I felt my body going rigid and told myself to relax. After all, I was supposed to be asleep. I was desperate to move, to scratch. To our great relief they eventually went out into the corridor where they stood smoking.

‘They’re saying,’ Frida told me, ‘that we might go out with them tonight. Just ignore them. I don’t think they’re that interested.’

She was right. They came back into the compartment and made a few remarks to us in German but we made it clear that we couldn’t understand them. The journey was agonizingly long, with the train stopping and starting with depressing regularity. We wouldn’t make the connection for Besançon that was for sure.

‘We’re going to need somewhere to stay in Nancy,’ I whispered to Frida in French. ‘We can’t wait at the station all night.’

‘I know, but it’s too risky to go to a hotel without papers.’

We sat there, glumly thinking. ‘There’s nothing for it,’ I said at last. ‘I’m going to find the guard. Perhaps he can help us.’

We were in luck. The guard was immediately understanding. He told me there was a small hotel near the station that was what he called ‘sympatique et respectable’. It could have been a brothel for all I cared. We had started on a journey that already seemed far too long. I huddled into the corner of the carriage and this time I really did doze off, to be wakened by Frida shaking me.

‘Nancy.

On arrive

.’

Still only half awake, I climbed down the high carriage steps, anxious to get away from the soldiers. I missed the last step and fell heavily.

‘Damn! My ankle … I think I’ve bust it,’ I shouted out in clear English.

Frida stared at me horrified. The soldiers were looking out of the carriage windows watching us. We froze for a long moment. After a few seconds they closed the carriage door. They waved as the train pulled away. Very slowly we started to breathe again.

We found the hotel easily. The proprietress was a severe-looking woman who received us without a word. She handed us the registration forms to sign but didn’t ask for our papers. We followed her upstairs to our room. Still not speaking, she motioned to two pairs of German army boots placed outside the next bedroom and then left us. We sat on the bed and looked at each other. Well, we had made it, but it didn’t look like there was going to be much sleep for us that night. Our unwanted neighbours were hardly conducive to a good rest. And there was always the prospect of a random check on the hotel by the authorities.