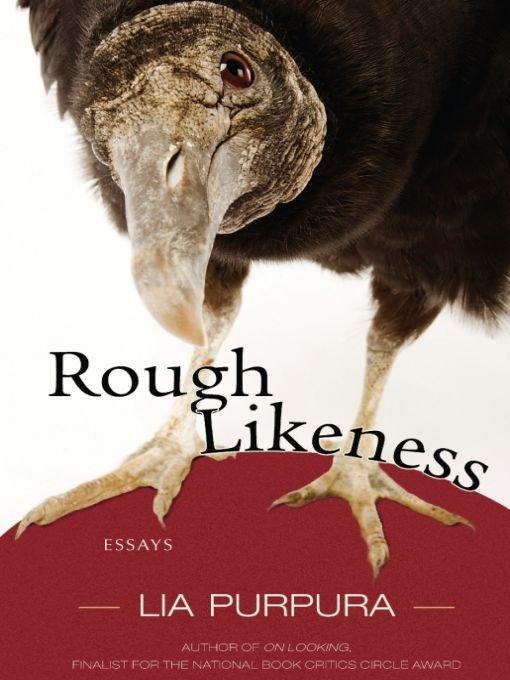

Rough Likeness: Essays

Read Rough Likeness: Essays Online

Authors: Lia Purpura

Table of Contents

For Jed and Joseph

Also by Lia Purpura

King Baby

(poems)

On Looking

(essays)

Stone Sky Lifting

(poems)

Increase

(essays)

Poems of Grzegorz Musial

(translations)

The Brighter the Veil

(poems)

(poems)

On Looking

(essays)

Stone Sky Lifting

(poems)

Increase

(essays)

Poems of Grzegorz Musial

(translations)

The Brighter the Veil

(poems)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I’d like to thank the editors of the following magazines in which these essays first appeared, sometimes in slightly different form:

Agni

: “Against ‘Gunmetal’”; “Being of Two Minds”; “The Lustres”; “Memo Re: Beach Glass”; “Two Experiments & a Coda”Arts & Letters

: “‘Try Our Delicious Pizza’”Black Warrior Review:

“‘Poetry Is a Satisfying of the Desire for Resemblance’ (Theme & Variations)”Crazyhorse:

“Street Scene”Ecotone:

“On Tools”Iowa Review:

“Augury”; “Jump”Ninth Letter:

“Remembering”Orion:

“On Coming Back as a Buzzard”; “There Are Things Awry Here”Seattle Review:

“Advice”Sonora Review:

“On Luxury”Southern Review:

“Gray”

“There Are Things Awry Here” was reprinted in

Best American Essays, 2011;

“On Coming Back as a Buzzard” and “Two Experiments & a Coda” were reprinted in

The Pushcart Anthology XXXV 2011

and

XXXIV 2010.

“The Lustres” and “Remembering” were named “Notable Essays” in

Best American Essays 2008

and

2009

.

Best American Essays, 2011;

“On Coming Back as a Buzzard” and “Two Experiments & a Coda” were reprinted in

The Pushcart Anthology XXXV 2011

and

XXXIV 2010.

“The Lustres” and “Remembering” were named “Notable Essays” in

Best American Essays 2008

and

2009

.

I am deeply grateful to Jed Gaylin, Maddalena Purpura, and Kent Meyers for advice of the revelatory variety, and for the lavish attention they’ve given to my work; to Dan Corrigan for fine tracking skills; Alan Kolc, for artistry; Bill Pierce and Hilarie Gaylin for pinch hitting; and to Loyola University’s Center for Humanities for generous summer study grants. And to Sarah Gorham, whose keen eye, light touch, and sustaining faith are rare and wondrous gifts. Daily, I know how lucky I am to have found her.

On Coming Back as a Buzzard

I know, coming back as a crow is a lot more attractive. If crows and buzzards do the same rough job—picking, tearing and cleaning up—who wouldn’t rather return as a shiny blue crow with a mind for locks and puzzles. A strong voice, and poem-struck. Sleek, familial, omen-bearing. Full of mourning and ardor and talk. Buzzards are nothing like this, but something other, complicated by strangeness and ugliness. They intensify my thinking. They look prehistoric, pieced together, concerned. I might simply say I feel closer to them—always have—and proceed. Because, really, as I turn it over, the problem I’m working on here, coming back as a buzzard, has not so much to do with buzzards after all.

A buzzard is

expected

at the table. The rush would be over by the time I got there and I, my lateness sanctioned, might rightfully slip in. I wouldn’t saunter, nor would I blow in dramatically—

flounce

, as my grandmother would say. The road would be the dinner table (just as the dinner table with its veering discussions, is always a road somewhere) and others’ distraction would resolve—well, I would resolve it—into a clean plate.

expected

at the table. The rush would be over by the time I got there and I, my lateness sanctioned, might rightfully slip in. I wouldn’t saunter, nor would I blow in dramatically—

flounce

, as my grandmother would say. The road would be the dinner table (just as the dinner table with its veering discussions, is always a road somewhere) and others’ distraction would resolve—well, I would resolve it—into a clean plate.

I would be missed if I were not there. Not at first, not in the frenzy, but later.

Without me, no outlines, no profiles come clear. The very idea of scaffolding is diminished.

“The smaller scraps are tastier” would have no defender. “Close to the bone” would fall out of use as a measure of sharply felt truth.

Without a chance to walk away from abundance, thus proving their wealth, none of the first eaters would be content with their portion. I make their bestowing upon the least of us possible.

With me around, mishaps—side of the highway, over a cliff, more slowly dispensed by poison—do not have to be turned to a higher purpose. I step in. I make use of.

And here, I’m whittling away at the problem.

As a buzzard, I’d know the end of a thing is precisely not that. Things go on, in their way. My presence making the end a beginning, reinterpreting the idea of abundance, allowing for the ever-giving nature of Nature—I’d know these not as religious thoughts. It’s that, apportioned rightly, there’s always enough, more than enough. “Nothing but gifts on this poor, poor earth” says Milosz, who understood perfectly the resemblance between dissolve and increase. Rain scours and sun burns away excesses of form. And rain also seeds, and sun urges forth fuses of green.

I’d love best the movement of stages and increments, to repeat “this bank and shoal of time” while below me banks and shoals of a body went on welling/receding, rising and dropping. I’d be perched on a wire, waiting, ticking off not the meat reducing, but how what’s left, like a dune, shifts and reconstitutes. Yes, it

looks

like I hover, and the hovering, I know, suggests a discomfiting eagerness. Malevolence. Why is that? I haven’t killed a thing. If the waiting seems untoward, it may be confirming something too real, too true: all the parts that slip from sight, can’t be easily had, collapse in on themselves and require digging, all the parts that promise small, intense bursts of sweetness unnerve us—while the easily abundant, the spans, the expanses (thick haunch, round belly and shoulder), all that lifts easily to another’s lips and retains its form till the end—seems pure. Right and deserved. Proper and lawful. Thus butchers have their neat diagrams. One knows to call for

chop, loin, shank, rump.

looks

like I hover, and the hovering, I know, suggests a discomfiting eagerness. Malevolence. Why is that? I haven’t killed a thing. If the waiting seems untoward, it may be confirming something too real, too true: all the parts that slip from sight, can’t be easily had, collapse in on themselves and require digging, all the parts that promise small, intense bursts of sweetness unnerve us—while the easily abundant, the spans, the expanses (thick haunch, round belly and shoulder), all that lifts easily to another’s lips and retains its form till the end—seems pure. Right and deserved. Proper and lawful. Thus butchers have their neat diagrams. One knows to call for

chop, loin, shank, rump.

I’d get to be one, who, when passed the plate, seeks first the succulent eye. This would mark me:

foreigner

. Stubborn lover of scraps and dark meat. Base. Trained on want and come to love piecemeal offerings—the shreds and overlooked tendernesses too small for a meal, but carefully, singularly gathered—like brief moments that burst: isolate beams of sun in truck fumes, underside of wrist against wrist, sudden cool from a sewer grate rising. I incline toward the tucked and folded parts—it’s that the old country can’t be bred out—the internals with names that lack correspondence, the sweetbreads and umbles, bungs, hoods, and liver-and-lights. If the road is a plate, then the outskirts of fields and settlements where piles are heaped are plates, too. And the gullies, the ditches, the alleys—all plates. I’d get to reorder your thoughts about troves, to prove the spilled and shoveled-aside to be treasure. To reconfer notions of milk and honey, and how to approach the unbidden.

foreigner

. Stubborn lover of scraps and dark meat. Base. Trained on want and come to love piecemeal offerings—the shreds and overlooked tendernesses too small for a meal, but carefully, singularly gathered—like brief moments that burst: isolate beams of sun in truck fumes, underside of wrist against wrist, sudden cool from a sewer grate rising. I incline toward the tucked and folded parts—it’s that the old country can’t be bred out—the internals with names that lack correspondence, the sweetbreads and umbles, bungs, hoods, and liver-and-lights. If the road is a plate, then the outskirts of fields and settlements where piles are heaped are plates, too. And the gullies, the ditches, the alleys—all plates. I’d get to reorder your thoughts about troves, to prove the spilled and shoveled-aside to be treasure. To reconfer notions of milk and honey, and how to approach the unbidden.

I resemble, as I suppose we all do, the things I consume: bent to those raw flaps of meat, red, torn, cast aside, my head also looks like a leftover thing, chewed. I have my ways of avoiding attention: vomit to turn away predators. Shit, like the elegant stork, on my legs to cool off, to disinfect the swarming microbes I tread daily. I am gentle. And cautious. I ride the thermals and flap very little (conserve, conserve) and locate food by smell. I’m a black V in air. A group of us on the ground is a

venue.

In the air we’re a

kettle.

venue.

In the air we’re a

kettle.

I reuse even the language.

A simple word,

aftermath,

structures my day. Sometimes I think

epic—

doesn’t everyone apply to their journey a story? Then

flyblown, feculent, scavenge

come—how it must seem to others—and the frame of my story’s reduced. Things are made daily again. The first eaters are furiously driven—by hunger, and brute need releasing trap doors in the brain. Such push and ambition! I hold things in pantry spots in my body and take out and eat what I’ve saved when I need it and so am never furious. On my plate, choice reduces. I take what I come upon, and the work of a breeze cools the bowl’s steaming contents. There’s a beauty in this singularity: consider bringing to each occasion your one perfect bowl, one neat fork/spoon/knife set. That when the chance comes, you’re given to draw the tine-curves between lips, pull, lick, tap clean the spoon’s curvature—and for these sensations, there’s ample time. Time pinned open, like the core of long summer afternoon.

aftermath,

structures my day. Sometimes I think

epic—

doesn’t everyone apply to their journey a story? Then

flyblown, feculent, scavenge

come—how it must seem to others—and the frame of my story’s reduced. Things are made daily again. The first eaters are furiously driven—by hunger, and brute need releasing trap doors in the brain. Such push and ambition! I hold things in pantry spots in my body and take out and eat what I’ve saved when I need it and so am never furious. On my plate, choice reduces. I take what I come upon, and the work of a breeze cools the bowl’s steaming contents. There’s a beauty in this singularity: consider bringing to each occasion your one perfect bowl, one neat fork/spoon/knife set. That when the chance comes, you’re given to draw the tine-curves between lips, pull, lick, tap clean the spoon’s curvature—and for these sensations, there’s ample time. Time pinned open, like the core of long summer afternoon.

Am I happy? Yes, in momentary ways. Which I think is a good way to feel about things that come when they will, and not when you will them. While I’m waiting, I get to be with the light as it shifts off the wet phone wire, catches low sun, holds, pearls and unpearls drops of water. If I bounce just a little, they shiver and fall, and my weight calls more pearls to me. There’s light over the blood-matted rib-fur, and higher up, translucing on the still-unripped ear of the fox. Light through drops of fresh resin on pine limbs, light on ditchwater neverminding the murk. I get fixed by spoors of light, silver shine on silks and tassels, light choosing the lowliest, palest blue gristle for lavishing. I wait at a height and from afar, up here on the telephone wire, with what looks like a hunch-shouldered burden. Below, the red coils of spilled guts gather dust on ground. Such a red and its steam in the cold gets to be

shock

—and

riches.

Any red interruption on asphalt, on hillside, at dune’s edge—

shock,

and not a strewn thing, not waste. Not a mess. Plump entrails crusting with sage and dirt tighten in sun: piercing that is an under-sung moment, filled with a tender resistance, a sweetness, slick curves and tangles to dip into, tear, stretch, snap, and swallow.

shock

—and

riches.

Any red interruption on asphalt, on hillside, at dune’s edge—

shock,

and not a strewn thing, not waste. Not a mess. Plump entrails crusting with sage and dirt tighten in sun: piercing that is an under-sung moment, filled with a tender resistance, a sweetness, slick curves and tangles to dip into, tear, stretch, snap, and swallow.

The problem with coming back as a buzzard is the notion of

coming back.

coming back.

I can’t believe in the coming-back.

Sure I play the dinnertime game, everyone identifying their animal-soul, the one they choose to reveal their best nature, the one, when the time comes, they hope fate will award them: strong eagle! smart dolphin! joyful golden retriever! But there’s the issue of where I’d have to go first, in order to make a return. And the idea of things I did or failed to do in a lifetime fixing the terms of my return—and the keeping of records, and just who’s totting it up. As soon as I imagine returning anew (brave stallion-reward, dung-beetle reproach) I lose heart. It’s too easy.

Other books

Charlie's Dream by Jamie Rowboat

Trump and Me by Mark Singer

Valentine Special Delivery by Kleve, Sharon

The Naked King by MacKenzie, Sally

Destry Rides Again by Max Brand

Captain Future 24 - Pardon My Iron Nerves (November 1950) by Edmond Hamilton

The Slave Ship by Rediker, Marcus

Merline Lovelace by Countess In Buckskin

Amos and the Chameleon Caper by Gary Paulsen

LADY UNDAUNTED: A Medieval Romance by Tamara Leigh