Rules of Civility (2 page)

Authors: Amor Towles

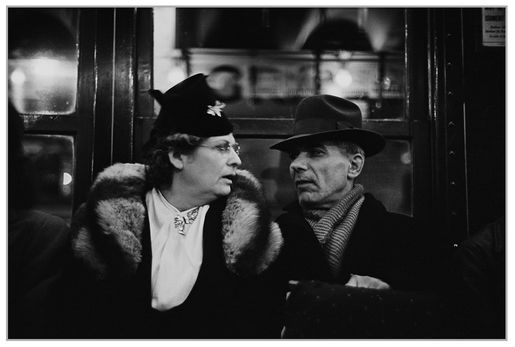

It happens to all of us. It's just a question of how many stops it takes. Two for some. Three for others. Sixty-eighth Street. Fifty-ninth. Fifty-first. Grand Central. What a relief it was, those few minutes with our guard let down and our gaze inexact, finding the one true solace that human isolation allows.

Â

How satisfying this photographic survey must have seemed to the uninitiated. All the young attorneys and the junior bankers and the spunky society girls who were making their way through the galleries must have looked at the pictures and thought:

What a tour de force. What an artistic achievement. Here at last are the faces of humanity!

What a tour de force. What an artistic achievement. Here at last are the faces of humanity!

But for those of us who were young at the time, the subjects looked like ghosts.

Â

The 1930s . . .

What a grueling decade that was.

I was sixteen when the Depression began, just old enough to have had all my dreams and expectations duped by the effortless glamour of the twenties. It was as if America launched the Depression just to teach Manhattan a lesson.

After the Crash, you couldn't hear the bodies hitting the pavement, but there was a sort of communal gasp and then a stillness that fell over the city like snow. The lights flickered. The bands laid down their instruments and the crowds made quietly for the door.

Then the prevailing winds shifted from west to east, blowing the dust of the Okies all the way back to Forty-second Street. It came in billowing clouds and settled over the newspaper stands and park benches, shrouding the blessed and the damned just like the ashes in Pompeii. Suddenly, we had our own Joadsâill clothed and beleaguered, trudging along the alleyways past the oil drum fires, past the shanties and flophouses, under the spans of the bridges, moving slowly but methodically toward inner Californias which were just as abject and unredeeming as the real thing. Poverty and powerlessness. Hunger and hopelessness. At least until the omen of war began to brighten our step.

Yes, the hidden camera portraits of Walker Evans from 1938 to 1941 represented humanity, but a particular strain of humanityâa chastened one.

A few paces ahead of us, a young woman was enjoying the exhibit. She couldn't have been more than twenty-two. Every picture seemed to pleasantly surprise herâas if she was in the portrait gallery of a castle where all the faces seemed majestic and remote. Her skin was flushed with an ignorant beauty that filled me with envy.

The faces weren't remote for me. The chastened expressions, the unrequited stares, they were all too familiar. It was like that experience of walking into a hotel lobby in another city where the clothes and the mannerisms of the clientele are so similar to your own that you're just bound to run into someone you don't want to see.

And, in a way, that's what happened.

Â

âIt's Tinker Grey, I said, as Val was moving on to the next picture.

He came back to my side to take a second look at this portrait of a twenty-eight-year-old man, ill shaven, in a threadbare coat.

Twenty pounds underweight, he had almost lost the blush on his cheeks, and his face was visibly dirty. But his eyes were bright and alert and trained straight ahead with the slightest hint of a smile on his lips, as if it was he who was studying the photographer. As if it was he who was studying us. Staring across three decades, across a canyon of encounters, looking like a visitation. And looking every bit himself.

âTinker Grey, repeated Val with vague recognition. I think my brother knew a Grey who was a banker. . . .

âYes, I said. That's the one.

Val studied the picture more closely now, showing the polite interest that a distant connection who's fallen on hard times deserves. But a question or two must have presented itself regarding how well I knew the man.

âExtraordinary, Val said simply; and ever so slightly, he furrowed his brow.

Â

By the summer that Val and I had begun seeing each other, we were still in our thirties and had missed little more than a decade of each other's adult lives; but that was time enough. It was time enough for whole lives to have been led and misled. It was time enough, as the poet said, to murder and createâor at least, to have warranted the dropping of a question on one's plate.

But Val counted few backward-looking habits as virtues; and in regards to the mysteries of my past, as in regards to so much else, he was a gentleman first.

Nonetheless, I made a concession.

âHe was an acquaintance of mine as well, I said. In my circle of friends for a time. But I haven't heard his name since before the war.

Val's brow relaxed.

Perhaps he was comforted by the deceptive simplicity of these little facts. He eyed the picture with more measure and a brief shake of the head, which simultaneously gave the coincidence its due and affirmed how unfair the Depression had been.

âExtraordinary, he said again, though more sympathetically. He slipped his arm under mine and gently moved me on.

We spent the required minute in front of the next picture. Then the next and the next. But now the faces were passing by like the faces of strangers ascending an opposite escalator. I was barely taking them in.

Â

Seeing Tinker's smile . . .

After all these years, I was unprepared for it. It made me feel sprung upon.

Maybe it was just complacencyâthat sweet unfounded complacency of a well-heeled Manhattan middle ageâbut walking through the doors of that museum, I would have testified under oath that my life had achieved a perfect equilibrium. It was a marriage of two minds, of two metropolitan spirits tilting as gently and inescapably toward the future as paper whites tilt toward the sun.

And yet, I found my thoughts reaching into the past. Turning their backs on all the hard-wrought perfections of the hour, they were searching for the sweet uncertainties of a bygone year and for all its chance encountersâencounters which in the moment had seemed so haphazard and effervescent but which with time took on some semblance of fate.

Yes, my thoughts turned to Tinker and to Eveâbut they turned to Wallace Wolcott and Dicky Vanderwhile and to Anne Grandyn too. And to those turns of the kaleidoscope that gave color and shape to the passage of my 1938.

Standing at my husband's side, I found myself intent on keeping the memories of the year to myself.

It wasn't that any of them were so scandalous that they would have shocked Val or threatened the harmony of our marriageâon the contrary, if I had shared them Val would probably have been even more endeared to me. But I didn't

want

to share them. Because I didn't want to dilute them.

want

to share them. Because I didn't want to dilute them.

Above all else, I wanted to be alone. I wanted to step out of the glare of my own circumstances. I wanted to go get a drink in a hotel bar. Or better yet, take a taxi down to the Village for the first time in how many years....

Yes, Tinker looked poor in that picture. He looked poor and hungry and without prospects. But he looked young and vibrant too; and strangely alive.

Â

Suddenly, it was as if the faces on the wall were watching me. The ghosts on the subway, tired and alone, were studying my face, taking in those traces of compromise that give aging human features their unique sense of pathos.

Then Val surprised me.

âLet's go, he said.

I looked up and he smiled.

âCome on. We'll come back some morning when it isn't so busy.

âOkay.

It was crowded in the middle of the gallery so we kept to the periphery, walking past the pictures. The faces flickered by like the faces of prisoners looking through those little square openings in maximum security cells. They followed me with their gaze as if to say:

Where do you think

you're

going?

And then just before we reached the exit one of them stopped me in my tracks.

Where do you think

you're

going?

And then just before we reached the exit one of them stopped me in my tracks.

A wry smile formed on my face.

âWhat is it? asked Val.

âIt's him again.

On the wall between two portraits of older women, there was a second portrait of Tinker. Tinker in a cashmere coat, clean shaven, a crisp Windsor knot poking over the collar of a custom-made shirt.

Val dragged me forward by the hand until we were a foot from the picture.

âYou mean the same one from before?

âYes.

âIt couldn't be.

Val doubled back to the first portrait. Across the room I could see him studying the dirtier face with care, looking for distinguishing marks. He came back and took up his place a foot from the man in the cashmere coat.

âIncredible, he said. It's the very same fellow!

âPlease step back from the art, a security guard said.

We stepped back.

âIf you didn't know, you'd think they were two different men entirely.

âYes, I said. You're right.

âWell, he certainly got back on his feet!

Val was suddenly in a good mood. The journey from threadbare to cashmere restored his natural sense of optimism.

âNo, I said. This is the earlier picture.

âWhat's that?

âThe other picture was after this one. It was 1939.

I pointed to the tag.

âThis was taken in 1938.

You couldn't blame Val for making the mistake. It was natural to assume that this was the later pictureâand not simply because it was hung later in the show. In the 1938 picture Tinker not only looked better off, he looked older too: His face was fuller, and it had a suggestion of pragmatic world-weariness, as if a string of successes had towed along an ugly truth or two. While the picture taken a year later looked more like the portrait of a peacetime twenty-year-old: vibrant and fearless and naïve.

Val felt embarrassed for Tinker.

âOh, he said. I'm sorry.

He took my arm again and shook his head for Tinker as for us all.

âRiches to rags, he said, tenderly.

âNo, I said. Not exactly.

Â

NEW YORK CITY, 1969

WINTERTIME

CHAPTER ONE

The Old Long Since

It was the last night of 1937.

With no better plans or prospects, my roommate Eve had dragged me back to The Hotspot, a wishfully named nightclub in Greenwich Village that was four feet underground.

From a look around the club, you couldn't tell that it was New Year's Eve. There were no hats or streamers; no paper trumpets. At the back of the club, looming over a small empty dance floor, a jazz quartet was playing loved-me-and-left-me standards without a vocalist. The saxophonist, a mournful giant with skin as black as motor oil, had apparently lost his way in the labyrinth of one of his long, lonely solos. While the bass player, a coffee-and-cream mulatto with a small deferential mustache, was being careful not to hurry him.

Boom, boom, boom,

he went, at half the pace of a heartbeat.

Boom, boom, boom,

he went, at half the pace of a heartbeat.

The spare clientele were almost as downbeat as the band. No one was in their finery. There were a few couples here and there, but no romance. Anyone in love or money was around the corner at Café Society dancing to swing. In another twenty years all the world would be sitting in basement clubs like this one, listening to antisocial soloists explore their inner malaise; but on the last night of 1937, if you were watching a quartet it was because you couldn't afford to see the whole ensemble, or because you had no good reason to ring in the new year.

We found it all very comforting.

We didn't really understand what we were listening to, but we could tell that it had its advantages. It wasn't going to raise our hopes or spoil them. It had a semblance of rhythm and a surfeit of sincerity. It was just enough of an excuse to get us out of our room and we treated it accordingly, both of us wearing comfortable flats and a simple black dress. Though under her little number, I noted that Eve was wearing the best of her stolen lingerie.

Â

Eve Ross . . .

Eve was one of those surprising beauties from the American Midwest.

In New York it becomes so easy to assume that the city's most alluring women have flown in from Paris or Milan. But they're just a minority. A much larger covey hails from the stalwart states that begin with the letter Iâlike Iowa and Indiana and Illinois. Bred with just the right amount of fresh air, roughhousing, and ignorance, these primitive blondes set out from the cornfields looking like starlight with limbs. Every morning in early spring one of them skips off her porch with a sandwich wrapped in cellophane ready to flag down the first Greyhound headed to Manhattanâthis city where all things beautiful are welcomed and measured and, if not immediately adopted, then at least tried on for size.

One of the great advantages that the midwestern girls had was that you couldn't tell them apart. You can always tell a rich New York girl from a poor one. And you can tell a rich Boston girl from a poor one. After all, that's what accents and manners are there for. But to the native New Yorker, the midwestern girls all looked and sounded the same. Sure, the girls from the various classes were raised in different houses and went to different schools, but they shared enough midwestern humility that the gradations of their wealth and privilege were obscure to us. Or maybe their differences (readily apparent in Des Moines) were just dwarfed by the scale of our socioeconomic strataâthat thousand-layered glacial formation that spans from an ash can on the Bowery to a penthouse in paradise. Either way, to us they

all

looked like hayseeds: unblemished, wide-eyed, and God-fearing, if not exactly free of sin.

all

looked like hayseeds: unblemished, wide-eyed, and God-fearing, if not exactly free of sin.

Other books

In Cold Blood by Anne Rooney

Fighting Back (Mercy's Angels) by Dallas, Kirsty

Julie and Romeo by Jeanne Ray

The Tale of the Wolf (The Kenino Wolf Series) by Cyrus Chainey

El vizconde demediado by Italo Calvino

Circus: Fantasy Under the Big Top by Ekaterina Sedia

Bride of the Isle by Maguire, Margo

Steps to Heaven: A Sgt Major Crane Novel by Cartmell, Wendy

Gravestone by Travis Thrasher

Ink (The Haven Series) by Torrie McLean