Russia (29 page)

Authors: Philip Longworth

Model of the St Sophia Cathedral, Kiev, as it would have looked in the eleventh century

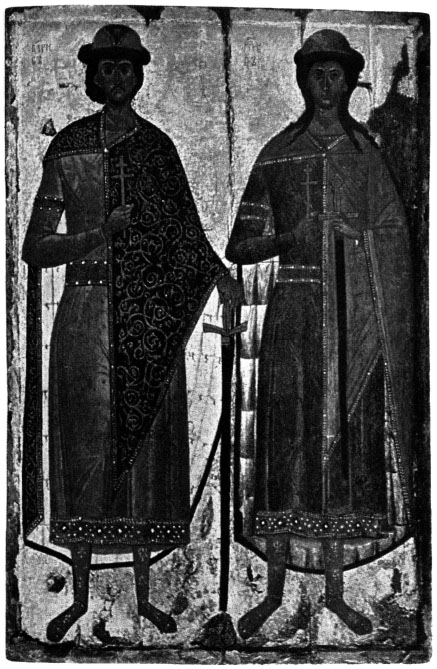

Saints Boris and Gleb: their martyrdom in 1015 was used to legitimate the Grand Princes of Kiev. Fourteenth-century icon of the Suzdal School

After all the pains which have been taken to bring this country into its present shape … I must confess that I can yet see it in no other light, than as a rough model of something meant to be perfected hereafter, in which the several parts do neither fit nor join, nor are well glewed

[sic]

together, but have been only kept so first by one great peg and now by another driven though the whole, which peg pulled out, the whole machine immediately falls to pieces.

3

Peter himself had served as the first peg. But who now could keep the Empire from crumbling?

Eighteenth-century Russia was dominated by women. Of Peter’s immediate successors, his widow, Catherine I, his half-niece Anna and his daughter Elizabeth together ruled Russia for more than thirty-two of the thirty-six years following his death, and Catherine II, known as ‘the Great’, reigned for more than thirty years thereafter. Peter II (1727—30), Ivan VI (1740-41) and Peter III (1761-2) interrupted the sequence, but had little impact on events.

The fact that most of these rulers were women did not diminish their authority, though there was some muted grumbling among the lower orders. However, none of them had received an education to fit them for supreme office, and apart from Catherine II they tended to be rather more dependent on one or two trusted advisers than most rulers. Cronyism and factionalism do seem to have increased at the Russian court, though this may be an impression given by observers who expected it to be so. The eighteenth century was a heyday for gossips. Empress Anna’s favourite, Biron (Bühren), was the dominant figure in the government, yet not — in Finch’s view at least - the linchpin that was needed. That function, he thought, was fulfilled by Count Andrei [Heinrich] Ostermann.

Ostermann, Russia’s ambassador to Sweden, was given charge of the Foreign Office after Peter’s death, and soon undertook a thorough reassessment of Russia’s foreign relations in the light of current circumstances. The findings of this complex exercise led him to conclude that, although Peter’s policy of alliance with Denmark and Prussia had helped to keep a usually complaisant Poland in tow, it involved risk and yielded insufficient dividends. Prussia had proved an unreliable ally, and the orientation towards the Baltic region was too narrow to serve the Empire’s interests in the new

era. Ostermann wanted to extend Russia’s influence in Europe as a whole, and, at the same time, to promote imperial growth. He was to achieve both these aims with brilliant economy, through

one

revolutionary turn of the diplomatic rudder.

The means was an alliance with Habsburg Austria, which was signed in August 1726. The two powers had a number of interests in common. They wanted to preserve the independence of their mutual neighbour Poland, the ‘sick man’ of Europe for the previous half century (its brilliant showing at the siege of Vienna in 1686 had been deceptive). They also wished to contain the Ottoman Empire, and to deter their other enemies - in particular France. But expansion to the south also figured in Ostermann’s strategy. His instructions to Ambassador Nemirov, Russia’s representative at peace talks with Turkey in 1735, included claims to the Crimea and the Kuban. As yet they were only negotiating points to be conceded, but they were not forgotten. Indeed, two years later Ostermann drew up a plan for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire. Strategists tend to plan for contingencies of course, but the Ottoman Empire was nowhere near collapse, as Ostermann well knew. These aims were for the longer term. A generation later they were to be pursued by Catherine the Great. Meanwhile the immediate thrust of Ostermann’s policy was directed further west.

4

One fruit of Ostermann’s policy of co-operation with Austria had ripened in the early 1730s, when the allies succeeded in getting their candidate, rather than France’s, elected as king of Poland — though not before a Russian army had advanced to France’s frontier on the Rhine. Russia had at last become a member of Europe’s major league. But the allies’ first war against the Turks ended in disappointment in 1739: Austria lost Belgrade, and although Russia regained Azov it was forbidden to harbour warships there.

5

In 1741, when Peter’s daughter Elizabeth was brought to the throne by a

coup d’état

carried out by the guards regiments, Ostermann was arrested and purged. But the alliance with Austria continued to hold firm, and was to serve as the launch pad for brilliant advances late in the century. Where, then, did the cause of failure in 1739 lie?

Peter had left an army of 200,000 men - seven battalions of crack infantry guards, fifty regiments of infantry, and thirty of dragoons. Apart from a few hussars, the remainder were mostly garrison troops. By 1730 the complement of the guards had increased — by five squadrons of cavalry guards and three battalions of infantry. Three regiments of cuirassiers had been added to the establishment, and fourteen militia regiments to defend Ukraine. By 1740 Russia had 240,000 men under arms, and by 1750 270,000 — not counting over 50,000 irregular troops, mostly Cossacks and

Kalmyks. Although the range of Russia’s military commitments meant that few more than 120,000 regulars could be fielded in a campaign, the army was growing in size.

Nor was it deficient in equipment. There were formidable magazines at Briansk, for operations in the west, and at Novo-Pavlovsk, for operations in the south, aside from the great arsenals in St Petersburg and Moscow. There were six cannon foundries, and two small-arms manufactories, one at Tula, the other outside St Petersburg, in which ‘everything is so well ordered that the

connoisseurs,

who have seen them, agree, that they are masterpieces of their kind’.

There was also provision now for specialist troops: an engineering school for the army; a navigation school for the navy. There were even some successful operations. In the Crimean campaign of 1736 Tatars had swarmed round the invading force as soon as it crossed the Perekop, but the regiments formed into square formation and marched on to the capital, Bakhchiserai. They captured it and sacked it, but they could not hold it. A third of the army had fallen sick, and the rest were exhausted from the great heat. However, in the following year the great Turkish citadel of Ochakov on the Dnieper estuary was taken, and its fortifications were demolished. Eighty-two brass cannon fell into Russian hands on that occasion, along with nine horsetail banners — the Ottoman emblems

of

senior rank. Those who had participated received a gratuity of four months’ pay from a grateful government. Four years later Swedish Finland was invaded and the well-defended strong-point of Wilmanstrand was stormed, taken, and ‘razed to the ground’.

6

Yet these successes were both hard-won and expensive. The root of the problem, according to an experienced officer, was not the enemy, however. ‘The Turks and Tatars … were what [the army] had least to dread; hunger, thirst, penury, continual fatigue, the marches in the intensest [sic] heat of the season, were much more fatal to it.’

7

And then there was the plague which broke out among the troops at Ochakov in 1738 and spread quickly into Ukraine.

8

No wonder that by the end of a campaign regiments were seriously under strength, some by as much as 50 per cent.

The great empires of the age depended on sea power, and both France and Britain had considerable navies. Russia’s, on the other hand was outclassed even by those of Spain and Holland. The navy had been neglected under Peter’s immediate successors. The proud Baltic fleet of thirty ships of the line with their attendant frigates, sloops and cutters had mostly been allowed to rot. Empress Anna made some attempt to halt the decline after 1730, but in 1734 when the city of Gdansk had to be besieged the

Admiralty found difficulty in fitting out even fifteen ships of the line, and some of those proved barely seaworthy.

9

A serious programme of naval construction finally got under way again in 1766. But three years later, when the government attempted to send a fleet to the eastern Mediterranean to support a Greek insurrection against the Turks, operational difficulties soon became apparent. Since the enemy commanded the Black Sea, ships had to be sent from the naval base of Kronstadt near St Petersburg. The long lines of communication were as problematic as the army’s logistical problems had been on the long marches to the Crimea. Without help from Britain the voyage might never have been managed.

Admiral Spiridonov set sail from Kronstadt with many troops on board in the summer of 1769. The flotilla under his command was bound for Hull, where Admiral Elphinston was fitting out another force of three ships of the line and two frigates. Things did not go well from the start. One of Spiridonov’s 66-gunners had to turn back almost at once, and a frigate was lost in the Gulf of Finland. The rest proceeded to Copenhagen, there to be joined by an 80-gun ship; but bad weather in the North Sea caused the flotilla to disperse. They eventually put into Portsmouth, some of the ships in poor condition and their crews tired. But the British Admiralty had instructed the authorities there to be helpful, and by the spring of 1770 they were repaired, refreshed and ready to sail for the Mediterranean, Admiral Elphinston carrying his flag in the 84-gun

Sviatoslav.

This tidy force of nine ships of the line, three frigates and three sloops sailed on to engage a superior Turkish fleet of fourteen bigger-gunned ships off the coast of Greece in the Bay of Chesme. A Scots officer in Russia’s service, Captain Samuel Greig, led the attack in the

Ratislav,

and fire-ships proved the decisive factor. As many as 200 Turkish sail were set ablaze. It was a famous victory

10

Greig was only one of many foreigners who were to influence the development of Russia’s armed services and its traditions. Scots, Greeks, Irishmen, Germans, Danes and Italians all served in them, as did a future American hero, John-Paul Jones. The best remembered are mostly those who held high rank: marshals Münnich and Lacy, generals Keith and Lowendal and a brother of Jeremy Bentham in the army; admirals Greig, Arf and Elphinston in the navy. However, the chequered career of a little-known naval captain, John Elton, draws attention to lesser men who served as instruments of Russian imperialism, and in less well-known areas of operation — in this case the territory of the lower Volga, Central Asia and Persia.

Elton was not a conventional sort of eighteenth-century hero. He won no brilliant victories, was not an enlightened reformer, had no political importance, and was unknown in the

haute monde,

though he was for a time a serious nuisance to officials, businessmen and diplomats. Venturesome, entrepreneurial and courageous, he was also choleric and unstable in his loyalties. At times, indeed, he appears as an anti-hero rather than a hero. Entering Russia’s service in the early 1730s, he was employed as an explorer and cartographer on land rather than being given a command with the fleet. He served with the so-called Orenburg expedition, set up in 1734 to secure the area round the confluence of the rivers Or and Ural, to explore the region’s potential for agriculture, mining and trade, to navigate the river Syr-Darya, and to investigate the suitability of the Aral Sea for navigation. Elton was involved with all these projects. He was also sent to Tashkent, disguised as a merchant. He surveyed the coast of the Aral Sea, which had been thought to be connected with the Caspian, looking for a possible site for a dock to build ships; he helped construct the citadel of Orenburg itself, and sounded the upper reaches of the Ural river to determine its possibilities for navigation.

It was while exploring the low-lying steppe beyond the east bank of the lower Volga that he mapped the great salt lake which still bears his name. His find soon proved very useful to the state, which maintained stocks of salt in order to guarantee the supply of this essential commodity and control its price. When the Stroganovs began to demand higher prices for Perm salt, Moscow was able to resist the demand thanks to Elton, and an ecological problem was also avoided, for the salt-boilers used a great deal of wood and the government now had a policy of forest conservation. Lake salt could be panned from the brine; it did not need boiling. Production at Lake Elton was expanded, and by the late 1750s it became by far the biggest source of salt in Russia.

11

Long before then, however, Elton, piqued at failing to receive the promotion he thought his due, had resigned the service and had immediately become involved in other ventures.

He set out to pioneer a new trade route from England, across Russia to Khiva, Bukhara and Tashkent. If such a route were found, he knew fortunes could be made by selling English woollen cloth there and bringing back valuable silks. While working with the Orenburg expedition he had questioned people who had crossed the Central Asian steppe, including Cossacks who had been taken as slaves on Bekovich-Cherkasskii’s ill-fated expedition of 1717. Concluding that the plundering Kyrgyz, Khivans and Karakalpaks made that approach too dangerous, he now set out to promote a new and safer route that went down the Volga, across the Caspian Sea to

Rasht, and thence by camel caravan across the desert to Meshed and points east. Having negotiated the approval of the Persian authorities, he took his proposal to the British minister at St Petersburg and the Russia Company in London. Recognizing that the route would give it an advantage over its rivals, the Levant and East India companies, the Russia Company seized the opportunity and appointed Elton its agent.

12