Sacre Bleu (4 page)

“Those are my shoes,” said round blond.

“Ah, so they are. I’ve made an arrangement with the madame. Lucien, shall we go? I believe lunch is in order. I may have not eaten in days.” He tipped his hat to the whores.

“Adieu,

ladies.

Adieu.”

Lucien joined his friend and they walked through the foyer and out the door into the bright sun, Henri a bit wobbly on the high heels.

“You know, Lucien, I find it very difficult to dislike a whore, but that blond, Cheesy Marie, she is called, has managed to provoke my displeasure.”

“Is that why you stole her shoes?”

“I did no such thing. A poor creature, trying to make her way—”

“I can see your own tucked in your waistband in the back, under your coat.”

“No they aren’t. That is my hunchback, an unfortunate consequence of my royal lineage.”

As they stepped off the curb to cross the street a shoe dropped out from under Henri’s coat and plopped on the cobblestones.

“Well, she was being unkind to you, Lucien. I will not stand for that. Buy me a drink and tell me what has happened to our poor Vincent.”

“You said you hadn’t eaten in days.”

“Well, buy me lunch then.”

“Did you ever get over that slut?”

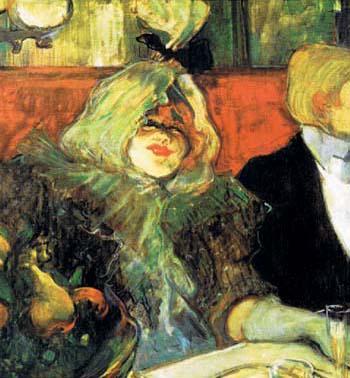

In Rat Mort

—Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, 1899

T

HEY DINED IN THE WINDOW OF THE

D

EAD

R

AT AND WATCHED PASSERSBY IN

gay summer apparel while Toulouse-Lautrec tried not to vomit again.

“Perhaps a cognac to settle your stomach,” said Lucien.

“An excellent idea. But I fear Cheesy Marie’s shoes are ruined.”

“C’est la vie,”

said Lucien.

“I think Vincent’s passing has upset my constitution.”

“Understandably,” said Lucien. He thought he, too, might have converted his repast to a spectral roar, if he’d tried to layer his dismay over a dead friend on top of three days and nights of debauchery as had Henri. They had both attended Cormon’s studio with Vincent, painted alongside him, drank, laughed, and argued color theory with him in the cafés of Montmartre. Henri had once challenged a man who insulted Vincent’s work to a duel, and might have killed him had he not been too drunk to fight.

Lucien continued, “I was in Theo’s gallery just last week. Theo said that Vincent was painting like a fiend, that Auvers agreed with him and he was doing good work. Even Dr. Gachet pronounced him recovered from his breakdown in Arles.”

“I liked his ideas about color and use of the brush, but his emotions were always so high. Perhaps if he could have afforded to drink more.”

“I don’t think that would have helped him, Henri. But why, if he was doing good work, and Theo had his expenses covered—”

“A woman,” said Toulouse-Lautrec. “When a suitable time has passed, we should call on Theo at the gallery and look at Vincent’s last paintings. I’ll bet there is a woman. No man kills himself but it is for a broken heart; surely you know that.”

Lucien felt a pain in his chest for his own memories and in sympathy for what must have been Vincent’s suffering. Yes, he could understand. He sighed and, staring out the window, said, “You know, Renoir always used to say that they were all one woman, all the same. An ideal.”

“You are incapable of having a discussion without bringing up your childhood around the Impressionists, aren’t you?”

Lucien turned to his friend and grinned. “Like you are incapable of having one without mentioning that you were born a count and grew up in a castle.”

“We are all slaves to our histories. I am simply saying that if we scratch van Gogh’s history, you will find a woman was at the heart of his disease.”

Lucien shuddered, as if he could shake the memory and melancholy off the conversation the way a dog shakes off water. “Look, Henri, van Gogh was an ambitious painter, talented, but he was not a steady man. Did you ever paint with him? He ate the paint. I’m trying to get the color of a

moulin

right and I look over and he has half a tube of rose madder on his teeth.”

“Vincent did enjoy a fine red,” said Henri with a grin.

“Monsieur,” said Lucien. “You are a dreadful person.”

“I’m simply agreeing with you—”

Toulouse-Lautrec stopped and stood up, his gaze trained out the window, over Lucien’s shoulder.

“You remember when you warned me off of Carmen?” said Henri, putting his hand on Lucien’s shoulder. “No matter how I felt, letting her go, it was the best thing for me, you said.”

“What?” Lucien twisted in his chair to see what Henri was looking at and caught sight of a skirt—no, a woman, out on the street in a periwinkle dress, matching parasol and hat. A beautiful dark-haired woman with stunningly blue eyes.

“Let her go,” said Henri.

In an instant Lucien was out of his chair and running out the door.

“Juliette! Juliette!”

Toulouse-Lautrec watched as his friend ran to the woman, then paused in front of her, as if not knowing what to do. Her face lit up at the sight of him, then she dropped her parasol and threw her arms around his neck, nearly leaping into his arms as she kissed him.

The waiter, who had been drawn out of the kitchen when he heard the door, joined Henri by the window.

“Oh là là,

your friend has captured himself a prize, monsieur.”

“And I fear it’s going to soon become very difficult being his friend.”

“Ah, perhaps he has some competition, eh?” The waiter pointed across the boulevard, where, straining to see around carriages and pedestrians, a small, twisted man in a brown suit and bowler hat was watching Lucien and the girl with a glint in his eye that looked to Henri like hunger.

1873

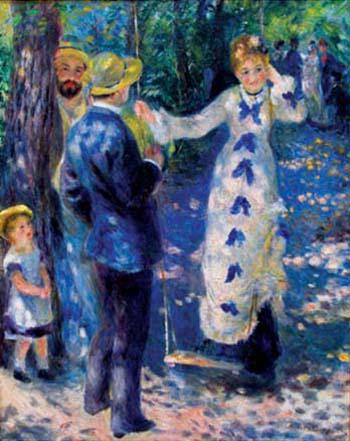

“… A delicate thing in a white dress with puffy sleeves and great ultramarine bows all down its front and at the cuffs.”

The Swing

—Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1876

L

UCIEN

L

ESSARD WAS TEN YEARS OLD WHEN HE WAS FIRST ENCHANTED BY

the sacred blue. It was a minor enchantment, really, but even the storm that drowns an empire must begin with a single raindrop, and later, one might only remember a spot of moisture on the cheek and having the thought,

Is that a bird?

“Is that a bird?” Lucien asked his father.

Père Lessard stood over the bread table in the back room of his bakery drawing patterns in the flour with a pastry brush, his forearms dusted white like great snowy hams.

“It’s a sailing ship,” said Père Lessard.

Lucien tilted his head this way and that. “Oh yes, now I see it.” He didn’t see it at all.

His father slouched, suddenly looking weary. “No you don’t. I’m no artist, Lucien. I am a baker. My father was a baker, and his father before him. Our family has fed the people of the butte for two hundred years. I have smelled of yeast and breathed the dust of flour my whole life. Not one day did our family or friends go hungry, even when there was war. Bread is my life, son, and before I die, I will have made a million loaves.”

“Yes, Papa,” said Lucien. He had seen his father slide into melancholy like this before, usually, like now, right before dawn when they were waiting for the first loaves to come out of the ovens. He patted his father’s arm, knowing that soon the bread would be ready and the bakery would boil with activity that would allow no time to grieve over ships that looked like birds.

“I would trade it all if I could lay down the colors of water like our friend Monet, or move paint like the joy in a young girl’s smile like Renoir. Do you know what I am talking about?”

“Yes, Papa,” Lucien said. He had no idea what his father was talking about.

“Is he going on about his pets again?” said Mother as she breezed into the room from the front, where she had been arranging the pastries in baskets. She was a stout, wide-bottomed woman who wore her chestnut hair up in a loose

chignon

that trailed tendrils that were either born of weariness or were simply attempting escape. Despite her size, she glided around the bakery as if dancing a waltz, her lips set in a bemused smile and a spark of annoyance in her eyes. Bemused and annoyed was more or less the lens through which Mère Lessard viewed the world. “Well, there are people waiting outside already, and it’s for the bread, not that paint stain you are raffling off.”

Père Lessard put his arm around Lucien’s shoulders. “Promise me, son, that you will become a great painter and that you will not let a spiteful woman ruin your life as I have.”

“A

beautiful

and spiteful woman,” said Mother.

“Of course,

ma chère,”

said Lucien’s father, “but I don’t need to warn him off of beauty, do I?”

“Warn him off taking in paint-spattered vagabonds as pets, then, would you?”

“We must forgive Madame her ignorance, Lucien. She is a woman and therefore hasn’t the capacity to appreciate art, but one day she will realize that my painter friends are great men, and she will repent for her unkind words.”

Lucien’s parents did this sometimes—talked through him as if he were a hollow tube simply muting the harsh tone and timbre of their words. He had learned that at these times, it was best to stare at a distant and neutral spot on the wall and resist the urge to appear attentive until one of them formulated an exit line sufficiently droll to dismiss the whole exchange.