Sacred Sierra (46 page)

Authors: Jason Webster

I looked over towards the Talaia on the other side of the valley, and for a moment I shivered as I remembered the great ball of black, billowing smoke that had risen from it only a few weeks past. The sense of fear and panic had gone now, but an echo of it still remained. One day we might not be so lucky. The firemen had managed to put the blaze out the night I had left here, saving our valley, and the village with it. But just in time. Ministers from Madrid had been helicoptered in to oversee the operation; over 6000 hectares of mountainside had been burnt. It had been the biggest forest fire of the summer on the Spanish mainland. And they had stopped it right on our doorstep. From here you would never even know that it had happened, but I’d driven over to the other side of the Talaia since; a weird, blackened landscape, the trees and bushes reduced to stumps of charcoal. Thankfully – and I didn’t know how – the sanctuary of Sant Miquel de les Torrocelles had been saved, but much of the pathway for the Pelegríns of Les Useres had been wiped out. It would be a very different pilgrimage to Sant Joan next year.

After glistening for a second on the mountain peak, the sun finally dipped out of sight, and we were struck by a wall of cold air. Time to get back inside. My eyes fell on some of the glasses of the home-made hooch I’d been pouring for our guests. Most of them were empty, but a few had only been half-drunk, it seemed. It was powerful stuff – I could already feel my own liver complaining from drinking too much of it. Perhaps my dreams of setting up a moonshine empire would have to wait. Might have to work a bit more on the recipe first.

Slowly, reluctantly, we began to pick up the pieces. It had been fun: a guitar had been produced at one point, a few tunes were played. Salud had been persuaded to dance for a while. Concha had sung more of her folk songs, El Clossa beating out the rhythm for her with his crutches. They’d both seemed happier than I’d seen them for a while. The

commune

was slowly fading to memory: we didn’t talk about the others any more.

I nibbled on some of the spare bits from the

jamón

I’d been slicing over the afternoon as plates, cups and cutlery were placed in the sink with a clatter. Perhaps we could leave the worst of it till the morning. Right now all either of us wanted to do was fall into a heap on the sofa.

I looked across at the now empty space of the kitchen; it was as if something had caught my eye.

‘What was that Concha was saying to you as she left?’ I said, suddenly remembering what I’d wanted to ask her.

Salud smiled, and carried on picking up the mess.

‘

Nada

,’ she said. ‘Nothing.’

I kept my eyes fixed on her until she looked up again, the smile breaking out into a laugh.

‘You know what she’s like,’ she said.

‘What was it?’ I said.

‘Something about the future.’

‘Not more ghosts this time.’

She shook her head, then paused, bending down to wipe some of the crumbs from the table, catching them in her cupped hand before standing up to look me in the eye again.

‘She said she could see children here.’

CODA: THE TREES

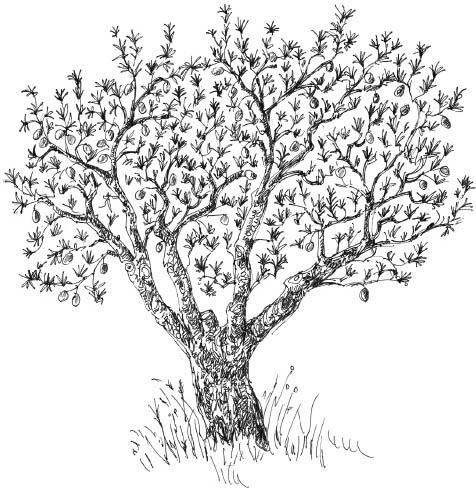

ALMOND

(

Prunus amygdalus; Ametller, Almendro

Valencian;

Almendro

Castilian.)

The first plant to come fully into bloom after midwinter, the almond is seen as a symbol of hope and the coming of spring. After the phylloxera disaster of the end of the nineteenth century, many local farmers moved from grapes to almonds as their staple produce, so that nowadays in February and March the hillsides south of the Penyagolosa are awash with delicate white and pink blossom, glistening in the low winter sun. Many of the trees have been abandoned as the farmers and

masovers

have left the countryside for the towns. But occasionally you catch a glimpse of a well-tended grove on a distant hillside, pink-orange soil laid bare by careful ploughing against a background of thick green.

Almonds are linked in mythology to the complicated stories of the Phrygian goddess Cybele and her lover Attis. It was said that Attis was conceived after Nana, the daughter of a river spirit, placed an almond in her breast. The almond came from a tree that had grown up from where the hermaphroditic daemon Agdistis had had his male genitalia cut off by the Greek gods. Attis would later castrate himself, thus giving rise to the Cybele-worshipping eunuch priests of Phrygia. Attis – and after him Mithras – is usually represented wearing the ‘Phrygian cap’, later commonly worn by the descendants of freed slaves in Rome; it subsequently became a symbol of liberty in the revolutionary movements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the French Marianne is portrayed to this day wearing a soft red conical cap.

Locally, almond milk, made by pounding almonds and honey

together

in a mortar and pestle and then adding water as required, as well as traditionally being a common refreshment is said to cure coughs (it is said to be more effective if the skin and shell of the almond are mixed in). Bitter almonds, despite being poisonous (they contain hydrogen cyanide), are supposed to help prevent drunkenness when eaten just before a night out. Perhaps a memory of this can be found in the common local custom of eating a plate of roasted, salted almonds with the first cold beer of the evening. If the barman himself has prepared the nuts it is quite common to come across the odd bitter specimen or two, usually resulting in the order of an immediate refill to help wash away the unpleasant taste.

Ibn al-Awam recommends a special fertiliser for almond trees, mixing animal dung with almond shells and leaves; your ‘farm workers’ should then urinate on this mixture until it rots and turns black, after which it can be mixed in with the soil around each tree.

CAROB

(

Ceratonia siliqua; Garrofer

Val.;

Algarrobo

Cast.)

Locally, the saying is that the carob tree needs to be able to ‘see the sea’ if it is to survive, a reference to the fact that temperatures below minus five can easily kill it. For that reason this small, compact tree is often found in the east-facing foothills with a cutoff point of roughly 500 metres above sea level. Traditionally it was cultivated to produce animal feed, particularly for pigs and horses, but in times of famine – most recently the period immediately after the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939 – the seeds were often eaten by humans as well. There are still many to be seen in the area, despite the reduced demand, often huddling alongside similar-sized olive trees. The carobs can be quickly recognised by the richer green of their leaves compared to the light grey tones of the olive.

Carob trees, along with holm oaks, are said to provide the best shade in which to hide from the midday sun. Ibn al-Awam says that mosquitoes will never come near carob wood.

The ‘carat’ system of measuring gold and precious stones comes from

the

ancient tradition of weighing gold against carob seeds. Eventually this was standardised so that a ‘carat’ equalled 0.2 grams.

Carobs are sometimes referred to as ‘St John’s bread’ as supposedly the Baptist lived off the seeds when he was in the desert.

Carob is said to be very effective against diarrhoea, while a syrup made from carob, lemon juice and honey is used locally for coughs.

CYPRESS

(

Cupressus sempervirens; Ciprés, Xiprer

Val.;

Ciprés

Cast.)

Spain has inherited from the Greeks and Romans the association of the cypress with death and the Underworld. Almost every graveyard you see – usually placed on the outskirts of a town or village – is filled with towering, dark-green cypress trees, hundreds of years old. As with the yew, it has also become a symbol of resurrection and eternal life – the ancient Persians associated the tree with Mithra, the god of light, while no Persian garden –

pairi-daeza

, hence ‘paradise’ – was complete without cypress trees. For the Phoenicians the cypress was sacred to the goddess Astarte, who later evolved into the Greek Aphrodite. Eros’s arrow was said to be made from cypress wood, while, according to some traditions, Christ’s cross was supposedly made from a mixture of cypress and cedar. The cypress was also Hercules’ tree: he himself planted a cypress grove at Daphne.

Cypress cones have traditionally been used as a cure for sciatica and rheumatism; in some local villages it is deemed sufficient simply to carry an odd number of them on one’s person, in a trouser pocket, for example. As a cure for haemorrhoids, others suggest boiling the cones in water for ten minutes before drinking, or applying externally via a sitz bath. Similar concoctions are said to be useful against migraines and chest problems. Cypress cones can also be left in wardrobes as a defence against moths. For the same reason, wardrobes and chests for keeping clothes were traditionally made from cypress wood – cut in winter during the time of a waning moon: not only did they keep the clothes inside safe, but the wood is impervious to woodworm. Beds were never made from cypress, however, as this was said to cause impotence.

ELDER

(

Sambucus nigra; Saüc

, Val.;

Sauco

Cast.)

Many

masos

in the area had an elder near the house as both an important medicinal plant, and also because it was thought to ward of the evil eye. A great number have now died, and it is no longer as common a tree as it once was. But the memory of its medicinal properties remains among the older generations. Locally, elderflower water was used to reduce bloating and as a cure for conjunctivitis, while elderflower tea was meant to cure bronchial problems. Pulp taken from younger branches of the tree were used to help heal burns. Pipes were also made from elder wood.

There is no hint in the Penyagolosa area of the elder being an ‘unlucky’ tree, as it is often regarded as being in the Northern European tradition.

ELM

(

Ulmus; Om

, Val.;

Olmo

Cast.)

As elsewhere, elms here have suffered greatly over recent decades, their presence ever diminishing in the face of the Dutch elm disease pandemic. Elms would often be seen in public squares, or in the countryside, often forming a transitional ecosystem between the dry mountainsides and the wetter areas around a river or lake. Some specimens remain, but the famous elm that stood outside the Sant Joan hermitage at the foot of the Penyagolosa has now died.

Elms were highly valued for the hardness of their wood, and the fact that elm wood was impervious to decay when kept permanently wet. For this reason it was commonly used for shipbuilding and bridges: Achilles used an elm trunk to make a bridge and escape the flooding waters of the Scamander and Simois rivers, enraged at his having slaughtered so many sons of Troy.

Applied externally to the skin, creams using elm pulp are used to help the healing of ulcers and wounds. Ibn al-Awam insists the trees should never be pruned, as this can hinder their growth.

HOLM OAK, HOLLY OAK

(

Quercus ilex; Carrasca

Val.;

Encina

Cast.)

The holm oak (‘holm’ being an old English word for ‘holly’) is the nearest there is to a national tree of Spain: it is estimated there are close to seven hundred million of them in the country – about fifteen for every Spaniard. It is a strong, slow-growing evergreen, with small, roundish, prickly leaves whose shape and size are similar to the holly’s (

Q. ilex ssp. rotundifolia

), or smooth, longer, thinner leaves almost like an olive’s (

Q. ilex ssp. ilex

). Traditionally its wood was used in the making of ships, resulting in a dramatic reduction in its numbers over previous centuries. It makes exceptionally good firewood and was one of the main sources of material for traditional charcoal-burners. It is particularly suited to dry conditions and likes limey soils, making it ideally suited to much of the Mediterranean basin.

The acorns of the holm oak, along with other oaks, are used to feed the pigs that produce the finest hams. There is even a categorisation system for

jamón serrano

, where acorns replace stars. A ‘five-acorn’ ham is the best you can get.

The shade of a holm oak is often regarded as one of the coolest places in summer, its shade as sought after as that of the carob tree, and for this reason they are often found planted near

masos

, offering farm workers a corner in which to escape the intensity of the sun. The acorns of the holm oak, made into a tea, were traditionally used as a cure for haemorrhoids.

For centuries the acorns were ground down and turned into flour in times of famine. Pliny the Elder says this was common in Hispania in the first century

BC

: ‘Sometimes … when there is a scarcity of corn, they are dried and ground, the meal being used to make a kind of bread. Even to this very day, in the provinces of Spain we find the acorn during the second course: it is thought to be sweeter when roasted in ashes’ (

Natural History

, Book XVI, ch. 6). This dependence on acorns among rural communities in Spain continued well into the twentieth century. Ibn al-Awam gives a recipe for making bread from ground acorns, but quotes Rhazes as saying that it can be harmful to the liver.