Salem Witch Judge (15 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

Joseph “was baptized with Mr. Stoughton present,” Samuel noted with pride. This seemed auspicious. Fifty-eight-year-old William Stoughton, deputy governor of the Province of New England, was a man of power and grace. After studying for the ministry at Harvard and Oxford, he had preached on both sides of the Atlantic. The Massachusetts court had granted him the honor of preaching the election sermon of 1668. Unlike most ministers, Stoughton “would not confine his powers to the pulpit,” the historian James Savage wrote. Stoughton served as a magistrate of the General Court during the 1670s and 1680s and, after 1686, as deputy governor, with the strong backing of Increase Mather. In 1692, when a new governor would need a man sufficiently wise to lead a court charged with hearing and judging multiple cases of suspected witchcraft, it would be Stoughton to whom he would turn.

Meanwhile, Samuel was planning to leave on a voyage that would keep him from home for most of little Joseph’s early life.

In September 1688, at the request of the Provincial Council, Samuel prepared to return to his country of birth. Increase Mather and other Massachusetts leaders were already in London trying to renew the old charter or at least to secure a new charter preserving some of their liberties. Samuel’s mission was to assist the Reverend Mather in securing New Englanders’ property rights.

Although the great majority of Americans could not afford transatlantic sojourns, Samuel’s father-in-law had made the same round-trip two decades before. In November 1669, when Hannah was eleven, John Hull and another Third Church founder sailed to the homeland in search of a minister. Hull returned eleven months later to find his “wife, daughter, servants, and all in health and safety.” His servants, indentured household employees who worked for a term, included relatives from England and America and unrelated people of English and African origins.

In 1688, as thirty-six-year-old Samuel anticipated the same voyage, he found the prospect of leaving his wife and four young children for months—possibly years—discomfiting. At the same time, he was intrigued to see his birthplace, which he could barely remember. He spent weeks packing. He set aside rounds of cheese, casks of Madeira wine, and live geese and sheep to slaughter on board and share with other passengers. His wife baked and packed plum cakes (stewed

plums in pie crusts) and pasties (meat and herbs in pastry shells). In October Gilbert Cole, who was admitted to the Third Church the same day as Samuel, bottled him “a barrel of beer for the sea.”

Samuel also packed books. He would read or reread them to pass the time on the ship, then give them away. He filled a trunk with a dictionary of biblical Hebrew, volumes by theologians Thomas Manton, Desiderius Erasmus, and John Preston, as well as stacks of pamphlets and sermons published at the Harvard College press, mementos of the New World that he hoped to share. He did not list every book he carried with him, but he took special care with one book, carefully wrapping it before adding it to the trunk. He did not yet know to whom he would give it.

This book, the latest edition of the complete Indian Bible, bound in calves’ leather, was so valuable it could not be bought. It was an evangelical work and as such could only be given away. The Indian Bible, one of the most important historic artifacts of seventeenth-century North America, remains an emblem of Puritan missionary zeal. Only twenty Indian Bibles exist in the world today. Each one is valued at more than two million dollars although they are unlikely to be available for sale.

The Indian Bible was John Eliot’s brainchild. Back in 1655, when the Cambridge-educated Roxbury minister was fifty, he developed sufficient fluency in Algonquian, after years of study, to begin translating the Gospel of Matthew into this Native American language. “I do very much desire to translate some parts of the Scriptures into their language and print some Primer in their language where to initiate and teach them to read.” He was pursuing a cultural goal: the seal of Massachusetts Bay Colony shows a Native American man ringed by the words, from Acts 16:9, “Come over and help us.” In 1646 the General Court ordered that “efforts to promote the diffusion of Christianity among aboriginal inhabitants be made with all diligence.” Three years later England’s Puritan-run Parliament enacted an Ordinance for the Advancement of Civilization and Christianity Among the Indians, which created the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Indians in New England, the first Protestant missionary society.

With the help of his Indian teachers—John Sassamon, Job Nesutan, and Cochenoe—Eliot translated the Gospel of Matthew. He sent this

sample translation to the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Indians in New England. Delighted, the corporation provided funding; a printing press; a printer from London, Marmaduke Johnson; and permission to translate the whole Bible into the Indian language. Eliot published the whole New Testament in Algonquian in 1661. Every copy was given away—one to King Charles II, some to English and American supporters of the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel, and hundreds to the Algonquian people. Missionaries on Martha’s Vineyard, the Kennebec River region in Maine, and Natick, Massachusetts, used this text to preach to and convert countless Native Americans.

Eliot’s crowning achievement was the complete Indian Bible including the Old Testament. It was a quasi-phonetic translation, intended for reading aloud by an English speaker to a listener who understands Algonquian. Thus the words “The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New,” became “Mamvsse wunneetupanatamwe up-biblum God naneeswe nukkone testament kah wonk wusku testament.” Marmaduke Johnson and the local printer, Samuel Green, published the first edition of the whole Indian Bible in 1663 at the Indian College in Cambridge. Each printing cost five hundred pounds. The amount of paper used in printing Indian Bibles exceeded that in all other seventeenth-century American publications combined. Eliot arranged for a second edition of the whole Indian Bible in 1685. It was from this second printing, which Samuel Sewall had supported financially, that he took his intended gift.

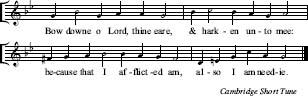

A few days before Samuel’s ship, the aptly named America, was to sail, his servants began carrying his luggage aboard. Samuel met the captain, to whom he gave a gift, and he chose the starboard cabin for himself. He called for a day of prayer at his home, at which the Reverend Willard preached on Psalm 143:10: “Teach me to do thy will; for thou are my God: Thy spirit is good; lead me into the land of uprightness.” Hannah was too ill with “the ague in her face” to venture downstairs to join the gathering, but Samuel led the group in singing Psalm 86, verses three to seven, in the Cambridge tune.

On October 29, as a sort of farewell gift, Samuel took his children Sam Jr., Hannah, and Betty, four of their young friends, and several other men to Hog Island for a picnic. He landed his boat “at the point”

of the island “because the water was over the marsh and wharf, being the highest tide that I ever saw there.” The party dined on turkey and other fowls, cooked over an open fire. They had “a fair wind” home, arriving at sunset.

Bow downe o Lord, thine eare,

& harken unto mee:

because that I afflicted am,

also I am needie.

2 Doe thou preserve my soule,

for gra-ci-ous am I:

o thou my God, thy servant save,

that doth on thee rely.

3 Lord pitty me, for I

daily cry thee unto.

4 Rejoyce thy servants soule: for Lord,

to thee mine [soul] lift I do.

5 For thou o Lord, art good,

to pardon prone withall:

and to them all in mercy rich

that doe upon thee call.

6 Jehovah, o doe thou

give eare my pray’r unto:

& of my sup-pli-ca-ti-ons

attend the voyce also.

7 In day of my distresse,

to thee I will complaine:

by reason that thou unto mee

wilt answer give againe.

On November 16, just before he was scheduled to leave Boston, an elderly Irish washerwoman named Mary Glover was hanged as a witch on Boston Common. Some months earlier, children in a house where Goodwife Glover worked began to act strangely. Their father, a Boston mason named John Goodwin, told them to stop. They said they were unable; Goody Glover had put a spell on them. She spoke in a foreign tongue, her native Irish, and she kept rag puppets, which were considered incriminating. The Reverend Cotton Mather was called in to investigate. He concluded that witchcraft was responsible and wrote it up as a 1689 essay, Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions. Mary Glover was brought to trial for witchcraft in Boston. Hoping to save herself, she confessed she was a witch. The court found her guilty and sentenced her to hang. Cotton Mather resolved then “never to use but just one grain of patience with any man that shall go to impose upon me a denial of devils and witches.” At eleven on the morning of her hanging, Samuel glanced out a window of his house and noted that “the widow Glover is drawn by to be hanged.”

The America set sail for England on November 22, an hour before sunset. As Samuel watched the town he loved fade into the distance, he poured himself a glass of Madeira and began to pray. Scripture and the Psalms would be his best companions at sea. A day later he observed, “I ate my wife’s pasty, the remembrance of whom is ready to cut me to the heart. The Lord pardon and help me.”

Traversing the Atlantic was treacherous and uncomfortable even for a wealthy merchant with a private cabin. The weather was bad for much of the trip. Wind, hail, snow, and huge waves pelted the ship. The ship took on water, prompting the captain to warn it might capsize. A storm sent Samuel’s chest flying across his cabin, breaking some glassware.

On the first of January 1689 news came from a passing ship that the Glorious Revolution, a major event in English history, had occurred. England had a new king. Leading English politicians who

were unhappy with James II had invited the Dutch prince William of Orange, a Protestant who was James II’s nephew and son-in-law, to challenge James II for England’s throne. William of Orange had landed at Torbay in England on November 5 and defeated James II, who fled to France, where he was welcomed by Louis XIV. William and his wife, James II’s daughter Mary, were now king and queen of England, which would now be run as a constitutional monarchy.

In the wake of the Glorious Revolution, Samuel’s peers in Boston, including Cotton Mather, Samuel Willard, other prominent ministers, and many merchants, would soon stage a revolution of their own. On April 19, 1689, eighty-six years before the April 19 famed for “the shot heard round the world,” they rallied local militia and imprisoned Governor Edmund Andros, his secretary, Edward Randolph, and several of their supporters in the fort overlooking Boston harbor. They placed Joseph Dudley, who was now seen as a conspirator, under house arrest in Roxbury. Within a few months the men of Boston would ship the Andros crowd back to England. Emboldened by the Glorious Revolution, which put two Protestants on the throne, New England’s leaders returned Governor Simon Bradstreet and the former deputies and assistants of the General Court to the offices they had held in 1686. This provisional government, which included Samuel, would last until a new royal governor, Sir William Phips, arrived with a new charter in 1692.

In England Samuel would not learn of Boston’s “quiet, well-bred, and bloodless revolution,” as his diary’s editor termed it, until late June, while on a visit to Cambridge with the Reverend Increase Mather and his fifteen-year-old son, Samuel. The New Englanders enjoyed Cambridge, Sewall reported: their innkeeper served them a boiled leg of mutton, “colly-flowers,” and “carrots, roast fowls, and a dish of peas. Three musicians came in, two harps and a violin, and gave us music.” Departing Cambridge early on June 29, the men headed to London in a coach with four horses, breakfasting at Epping. By late morning they reached a coffeehouse where mail awaited them. Tearing open a letter, Samuel Sewall “read the news of” the revolution in Boston. He gave the letter “to Mr. Mather to read. We were surprised with joy.” Yet another event at home that Samuel was absent for, of a more personal nature, was the admission of his wife to full membership in the Third Church on January 1, 1689.

That same January week, on board his ship to England, Samuel sighted shorebirds—“a gray linnet and a lark, I think.” One foggy morning the captain “trimmed sharp for our lives,” narrowly avoiding “horrid, high, gaping rocks” off the Isles of Scilly. Arriving at Dover on January 13, Samuel stepped on land for the first time in seven weeks. It was the Sabbath, so he walked to a malt-house to hear a Puritan minister preach from Isaiah 65:9: “And I will bring forth a seed out of Jacob, and out of Judah an inheritor of my mountains: and mine elect shall inherit it, and my servants shall dwell there.”

Samuel felt like a tourist in England. He introduced himself to people as “a New England man,” and after six months he wrote, “I am a stranger in this land.” His base of operations was a room above a London shop owned by his wife’s “Cousin Hull,” the son of John Hull’s late brother, Edward. Edward Hull Jr. ran a haberdashery, the Hat-in-Hand, in Aldgate, a neighborhood just northeast of the Tower of London. At that time London was the world’s largest city, with half a million inhabitants. Its city center, destroyed by the Great Fire of

1666, was now mostly rebuilt. London, the seat of English government, was already famous for its media, culture, and markets.