Salt (23 page)

Until 1766, Lorraine was the independent kingdom of Lotharingia, named after the ninth-century king Lothair. Long before France acquired it, Lorraine was already famous for the richness of its brine springs, which have denser brine than in most of Germany and have been exploited since prehistoric times. In the Seille Valley of Lorraine, salt has been produced since the time of the Celts. The Seille, whose name means “salty,” is a tributary of the Moselle. The Celtic salt mine had been abandoned, but in the tenth century, Lotharingians began boiling brine with wood fires. Salt could be moved along the Moselle to Alsace, Germany, and Switzerland. Choucroute, surkrut, and sauerkraut were all made with Lorraine salt.

Surkrut was a dish for special occasions—weddings and state banquets. By the sixteenth century, a trade existed in Alsace known as a

surkrutschneider

. Literally sauerkraut tailors, surkrutschneiders chopped cabbage and salted it in barrels with anise seeds, bay leaves, elderberries, fennel, horseradish, savory, cloves, cumin, and other herbs and spices. Each surkrutschneider had his own secret recipe.

By the early eighteenth century, the French had their own word for surkrut:

sorcrotes

. In 1767, encyclopedist and philosopher Denis Diderot mentioned

saucroute

in a letter, and finally, in 1786, on the eve of the French Revolution, the word

choucroute

first appeared. By then, choucroute was generally served mixed with or as a bed underneath other salted foods, and the dish was called

choucroute garnie.

Originally it was served with salted fish, especially herring. But gradually salted fish was replaced by salted meats—an assortment of sausages and cured cuts of pork piled festively on a large platter of seasoned, salt-cured cabbage.

Like wine, salt, and salted meats, choucroute was an important international trading commodity for Alsace.

Sauerkraut made its notable debut off the continent in 1753, when an English doctor informed the admiralty that it prevented scurvy. Many medieval Europeans had heeded Cato’s words on the health benefit of cabbage, fashioning plasters and cough medicines from the leaves. The healing of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II by application of cabbage plasters in 1569 was widely publicized.

Once again, cabbage was medicine. The British navy set up “sauerkraut stores” in British ports so that all Royal Navy vessels could set sail provisioned with sauerkraut. Captain James Cook had it served to his crew with every meal. At the same time, across the channel in Paris, it remained banquet food for the royal court. Marie Antoinette, whose father was from the house of Lorraine, championed choucroute at court. This classic early-twentieth-century recipe was little changed from that time.

You can buy choucroute ready-made at the Charcuterie or at a prepared-food shop; but in the countryside this is difficult to find; we are giving the recipe in the simplest way possible.

Take a round, well-shaped white cabbage, clean it, pulling off the green or wilted leaves, split the cabbage in quarters and remove the thick sides that form the heart. Then cut the cabbage in slices thick as a straw and prepare the following brine:

Take a small barrel that once contained white wine, clean it thoroughly and cover the bottom with a layer of coarse salt; then put on top of this a layer of cabbage cut into little strips; sprinkle with juniper berries and here and there peppercorns, press the layer in well but without letting it break up; add a new layer of salt, a bed of cabbage, juniper berries and pepper and continue taking care to press well.

It takes about two pounds of salt for a dozen cabbages. The barrel should be only three quarters filled, cover the choucroute with a piece of loosely-woven linen, then a wooden lid that fits completely inside the barrel. Put a 30 kilo [66 pound] weight on the lid. (If you don’t have a weight use a rock or a paving stone.) Once fermentation begins, which happens after a short while, the lid drops down and becomes covered with water formed by the salt. You remove this water but take care to leave a little on the lid.

You can use the choucroute at the end of a month, but once you take some, you have to take care to wash the cloth and the lid and replace them, adding a little fresh water on the top to replace what has been taken.

The fermentation gives the choucroute a bad smell, but don’t worry about it, because you wash the choucroute with a little water before serving and the bad taste vanishes.

Choucroute garnie:

Wash the choucroute, changing the water several times, and squeeze it well in your hands; when it is drained so that no more water is in it, prepare a casserole, placing a piece of lard in the bottom (the fat side should touch the dish). Place on it a bed of choucroute not too tightly packed, salt, pepper, juniper berries, a bit of fat from a roast, a small slice of

lard maigre

[a baconlike cut of pork from the chest], a small sausage, and half a raw

cervelas

[a stumpy all-pork sausage, usually seasoned with garlic. The name comes from pork brains,

cervelle,

which are rarely included anymore]. Put in another layer of choucroute, salt, pepper, juniper berries, roast fat, lard maigre, sausage, cervelas, and continue in this way until there is no more choucroute. Moisten the entire thing with a bottle of white wine and two glasses of stock. Cover and let cook for five hours over a low heat.

Finally, remove the fat from the top and press hard on the choucroute with a spoon, then place a platter over the casserole and turn it upside down so that your choucroute comes out shaped like a pâté.

For two or three people, you can use two pounds of choucroute. It is better reheated the next day.—

Tante Marie,

La veritable cuisine de famille

(Real family cooking), 1926

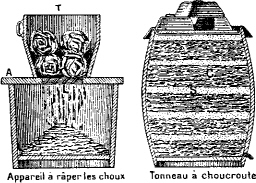

A diagram showing how to make choucroute from the 1938 edition of

Larousse Gastronomique

by Prosper Montagné.

I

N THE TIME

of Pliny, a Roman legionnaire named Peccaius established a sea-salt pond in the estuary of the Rhône to raise money to pay the salaries of the enormous Roman army fighting in Gaul. The marshy area, including the swamp known as the Camargue, was well suited to salt making. Located both on the Mediterranean and on a river that led into Gaul and later France, the Italians recognize the Rhône estuary as an ideal location for their salt making. A short distance from where the Genoese had their saline in Hyères, other Italians, especially the Tuscans, invested in saltworks in the estuary of the Rhône.

In the thirteenth century, a group of religious extremists based in the town of Albi and known as the Albigensians inspired Pope Innocent III to launch a series of crusades to cleanse the region of “heretics.” Asked how to recognize a heretic from a true believer, one crusader, according to legend, said, “Kill them all. God knows his own.” The chaos that ensued from this approach is known as the Albigensian Wars. In 1229, Louis IX, the fifteen-year-old king of France, concluded a treaty to end the French campaign against the Albigensians, in which the Rhône estuary was ceded to the French Crown.

This gave France its Mediterranean coast, and in 1246 Louis established the first French Mediterranean port, a walled city named Aigues-Mortes, which means “dead waters.” These dead waters lay beyond the massive ramparts that enveloped the city, in a vast expanse of salt evaporation ponds built out into the Mediterranean. Louis wanted salt revenue to finance his dream of leading a Crusade to the Middle East, which he did two years later. He captured an Egyptian port before being defeated and taken prisoner. For this he has been ever after known in French history as Saint Louis. When he finally returned to France in 1254, his saltworks, milky ponds where tall pink flamingos waded, were still producing salt and state revenue.

In 1290, the Crown bought nearby Peccais, site of the Roman works, and the two became the third largest producer of salt in the Mediterranean Sea, after Ibiza and Cyprus. This idea of Saint Louis, for Mediterranean saltworks to be controlled for royal revenue, would one day grow into what would be remembered as one of the greatest disasters of French royal administration.

T

HE MEDITERRANEAN SALTWORKS

shipped their product up the Rhône as far as Lyon. The salt was also carried on land routes over the mountains of Provence to nearer destinations such as Roquefort-sur-Soulzon.

It is the presence of salt throughout France, along with either cows, goats, or sheep, that has made it the notoriously ungovernable land of 265 kinds of cheese. French cheese makers were trying to be neither difficult nor original. They were all trying to preserve milk in salt so they could have a way of keeping it as a food supply. But with different traditions and climates, the salted curds came out 265 different ways. At one time there were probably far more variations than that.

The cheese made in the Aveyron, a mountainous area of dramatic rock outcropping and thin topsoil, is as old as its famous salt source. Pliny praised a cheese from these mountains above the Mediterranean coast that was probably a forerunner of the now famous Roquefort. According to a widely believed, though not well-documented, legend, Charlemagne passed through the area after his disastrous Spanish campaign of 778. The monks of the nearby monastery of St.-Gall served the emperor Roquefort cheese, and he immediately busied himself cutting out the moldy blue parts, which he found disgusting. The monks convinced him that the blue was the best part of the cheese—an effort for which they were rewarded with the costly task of providing him with two wheels of Roquefort a year until his death in 814.

Other books

No Place by Todd Strasser

Day of Reckoning by Stephen England

Seducing Officer Barlowe by Paige Tyler

Siege At The Settlements (Book 6) by Craig Halloran

SEAL Brotherhood 06 - SEAL My Destiny by Sharon Hamilton

Away in a Murder by Tina Anne

Pharaoh by Valerio Massimo Manfredi

MemoRandom: A Thriller by Anders de La Motte

Dance in the Dark by Megan Derr

Tokyo Tease by Luna Zega