San Andreas

San Andreas

To David and Judy

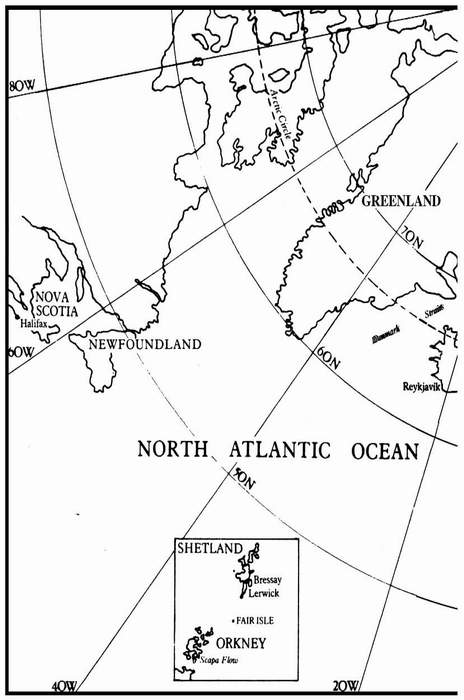

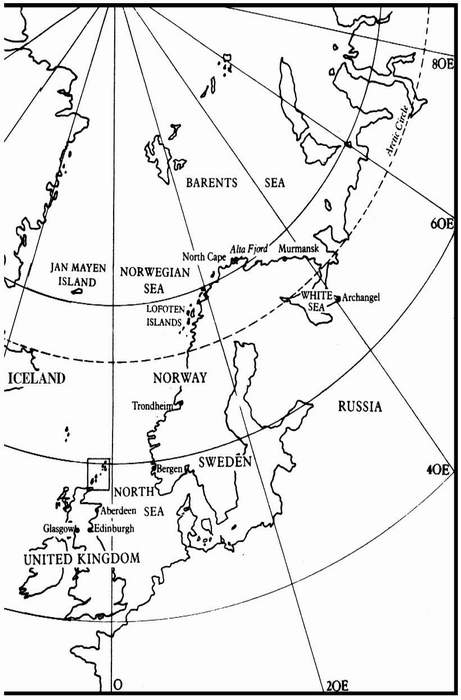

There are three distinct but inevitably interlinked elements in this story: the Merchant Navy (officially the Mercantile Marine) and the men who served in it: Liberty Ships: and the units of the German forces, underseas, on the seas and in the air, whose sole mission was to seek out and destroy the vessels and crews of the Merchant Navy.

1 At the outbreak of war in September 1939 the British Merchant Navy was in a parlous state indeedââpitiable' would probably be a more accurate term. Most of the ships were old, a considerable number unseaworthy and some no more than rusting hulks plagued by interminable mechanical breakdowns. Even so, those vessels were in comparatively good shape compared to the appalling living conditions of those whose misfortune it was to serve aboard those ships.

The reason for the savage neglect of both ships and men could be summed up in one wordâgreed.

The fleet owners of yesteryearâand there are more than a few around todayâwere grasping, avaricious and wholly dedicated to their high priestessâprofits at all costs, provided that the cost did not fall on them. Centralization was the watchword of the day, the gathering in of overlapping monopolies into a few rapacious hands. While crews' wages were cut and living conditions reduced to barely subsistence levels, the owners grew fat, as did some of the less desirable directors of those companies and a considerable number of carefully hand-picked and favoured shareholders.

The dictatorial powers of the owners, discreetly exercised, of course, were little short of absolute. Their fleets were their satrap, their feudal fiefdom, and the crews were their serfs. If a serf chose to revolt against the established order, that was his misfortune. His only recourse was to leave his ship, to exchange it for virtual oblivion, for, apart from the fact that he was automatically blackballed, unemployment was high in the Merchant Navy and the few vacancies available were for willing serfs only. Ashore, unemployment was even higher and even if it had not been so, seamen find it notoriously difficult to adapt to a landlubber's way of life. The rebel serf had no place left to go. Rebel serfs were very few and far between. The vast majority knew their station in life and kept to it. Official histories tend to gloss over this state of affairs or, more commonly, ignore it altogether, an understandable myopia.

The treatment of the merchant seamen between the wars and, indeed, during the Second World War, does not form one of the more glorious chapters in British naval annals.

Successive governments between the wars were perfectly aware of the conditions of life in the Merchant Navyâthey would have had to be more than ordinarily stupid not to be so awareâso successive governments, in largely hypocritical face-saving exercises, passed a series of regulations laying down minimum specifications regarding accommodation, food, hygiene and safety. Both governments and owners were perfectly awareâin the case of the ship-owners no doubt cheerfully awareâthat regulations are not laws and that a regulation is not legally enforceable. The recommendationsâfor they amounted to no more than thatâwere almost wholly ignored. A conscientious captain who tried to enforce them was liable to find himself without a command.

Recorded eyewitness reports of the living conditions aboard Merchant Navy ships in the years immediately prior to the Second World Warâthere is no reason to question those reports, especially as they are all so depressingly unanimous in toneâdescribe the crews' living quarters as being so primitive and atrocious as to beggar description. Medical inspectors stated that in some instances the crews' living quarters were unfit for animal, far less human, habitation. The quarters were invariably cramped and bereft of any form of

comfort. The decks were wet, the men's clothes were wet and the mattresses and blankets, where such luxuries were available, were usually sodden. Hygiene and toilet facilities ranged from the primitive to the non-existent. Cold was pervasive and heating of any formâexcept for smoking and evil-smelling coal stovesâwas rare, as, indeed was any form of ventilation. And the food, which as one writer said would not have been tolerated in a home for the utterly destitute, was even worse than the living quarters.

The foregoing may strain the bounds of credulity or, at least, seem far-fetched, but respectively, they should not and are not. Charges of imprecision and exaggeration have never been laid at the doors of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine or the Registrar General. The former, in a pre-war report, categorically stated that the mortality rate below the age of fifty-five was twice as high for seamen as it was for the rest of the male population, and statistics issued by the latter showed that the death rate for seamen of all ages was 47% in excess of the national average. The killers were tuberculosis, cerebral hæmorrhage and gastric or duodenal ulcers. The incidence of the first and last of those is all too understandable and there can be little doubt that the combination of those contributed heavily to the abnormal occurrence of strokes.

The prime agent of death was unquestionably tuberculosis. When one looks around Western

Europe today, where TB sanatoria are a happily and rapidly vanishing species, it is difficult to imagine just how terrible a scourge tuberculosis was just over a generation ago. It is not that tuberculosis, worldwide, has been eliminated: in many underdeveloped countries it still remains that same terrible scourge and the chief cause of death, and as recently as the early years of this century TB was still the number one killer in Western Europe and North America. Such is no longer the case since scientists came up with the agents to tame and destroy the tubercle bacillus. But in 1939 it was still very much the case: the discovery of the chemotherapeutic agents, rifampin, para-aminosalicylic acid, isoniazid and especially streptomycin, still lay far beyond a distant horizon.

It was upon those tuberculosis-ridden seamen, ill-housed and abominably fed, that Britain depended to bring food, oil, arms and ammunition to its shores and those of its allies. It was the

sine qua non

conduit, the artery, the lifeline upon which Britain was absolutely dependent: without those ships and men Britain would assuredly have gone under. It is worth noting that those men's contracts ended when the torpedo, mine or bomb struck. In wartime as in peacetime the owners protected their profits to the bitter end: the seaman's wages were abruptly terminated when his ship was sunk, no matter where, how, or in what unimaginable circumstances. When an owner's ship went down he shed no salt tears, for his ships were insured, as

often as not grossly over-insured: when a seaman's ship went down he was fired.

The Government, Admiralty and ship-owners of that time should have been deeply ashamed of themselves: if they were, they manfully concealed their distress: compared to prestige, glory and profits, the conditions of life and the horrors of death of the men of the Merchant Navy were a very secondary consideration indeed.

The people of Britain cannot be condemned. With the exception of the families and friends of the Merchant Navy and the splendid volunteer charitable organizations that were set up to help survivorsâsuch humanitarian trifles were of no concern to owners or Whitehallâvery few knew or even suspected what was going on.

2 As a lifeline, a conduit and an artery, the Liberty Ships were on a par with the British Merchant Navy: without them, Britain would have assuredly gone down in defeat. All the food, oil, arms and ammunition which overseas countriesâespecially the United Statesâwere eager and willing to supply were useless without the ships in which to transport them. After less than two years of war it was bleakly apparent that because of the deadly attrition of the British Merchant fleets there must soon, and inevitably, be no ships left to carry anything and that Britain would, inexorably and not slowly, be starved into surrender. In 1940, even the indomitable Winston

Churchill despaired of survival, far less ultimate victory. Typically, the period of despair was brief but heaven only knew that he had cause for it.

In nine hundred years, Britain, of all the countries in the world, had never been invaded, but in the darkest days of the war such invasion seemed not only perilously close but inevitable. Looking back today over a span of forty and more years it seems inconceivable and impossible that the country survived: had the facts been made public, which they weren't, it almost certainly would not.

British shipping losses were appalling beyond belief and beggar even the most active imagination. In the first eleven months of the war Britain lost 1,500,000 tons of shipping. In some of the early months of 1941, losses averaged close on 500,000 tons. In 1942, the darkest period of the war at sea, 6,250,000 tons of shipping went to the bottom. Even working at full stretch British shipyards could replace only a small fraction of those enormous losses. That, together with the fact that the number of operational U-boats in that same grim year rose from 91 to 212 made it certain that, by the law of diminishing returns, the British Merchant Navy would eventually cease to exist unless a miracle occurred.

The name of the miracle was Liberty Ships. To anyone who can recall those days the term Liberty Ships was automatically and immediately linked with Henry Kaiser. Kaiserâin the circumstances it was ironic that he should bear the same name as

the title of the late German Emperorâwas an American engineer of unquestioned genius. His career until then had been a remarkably impressive one: he had been a key figure in the construction of the Hoover and Coulee dams and the San Francisco bridge. It is questionable whether Henry Kaiser could have designed a rowing-boat but that was of no matter. He almost certainly had a better understanding of prefabrication based on a standard and repeatable design than any other person in the world at the time and did not hesitate to send out contracts for part-construction to factories in the United States that lay hundreds of miles from the sea. Those sections were transmitted to shipyards for assembly, originally to Richmond, California, where Kaiser directed the Permanente Cement Co., and eventually to other shipyards under Kaiser's control. Kaiser's turnover and speed of production stopped just short of the incredible: he did for the production of merchant vessels what Henry Ford's assembly lines had done for the Model T Ford. Until then, as far as ocean-going vessels were concerned, mass production had been an alien concept.