Sand rivers (5 page)

With Nicholson 1 went on a "reconnaissance" ("We don't say 'game

24

..^»..r

(Below) Kiny,upini aiinp.

\ ->

i^

^y,

(Above) Leaf-nosed bat. (Ri^ht) Impala.

r

v^. «^

r

i%

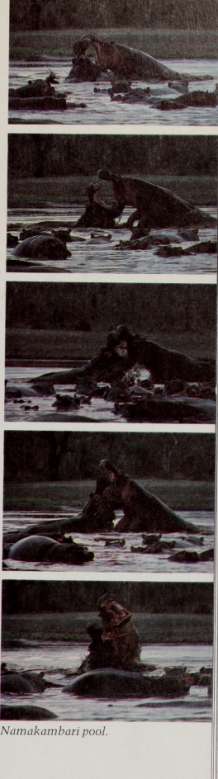

Namakamhah pool

•%ii^

•-^-cr*.»r

SAND RIVERS

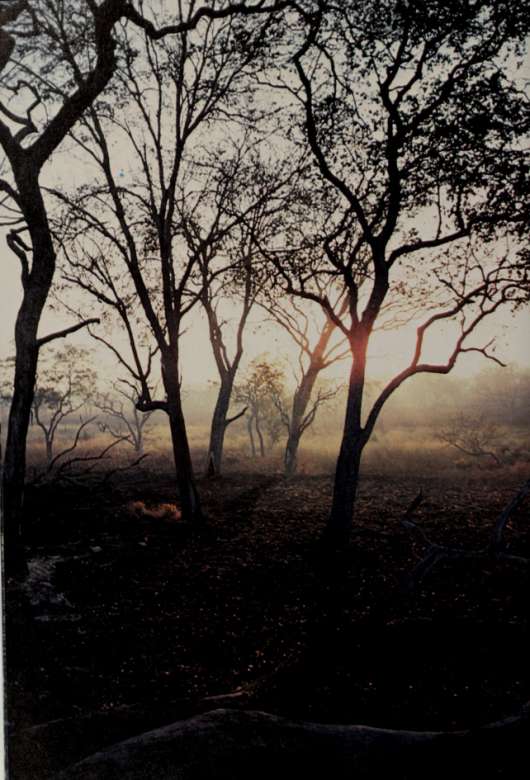

run' here in the Selous; that's tourist talk"), crossing a savanna of coarse grass set about with isolated leadwood trees; the leadwood is a species of combretum named for its durability - a dead tree may stand for many years. Soon we turned west into low terminalia woodland, arriving eventually at Kilunda Pool, a small pan where big green monitor lizards shot off low limbs of baobab into the water. These unexpected pans are usually accompanied by termite hills, and Alan Rodgers has suggested that the red mounds, which are partly subterranean, and also the root systems of the large trees such as tamarind and ebony that grow on them, penetrate the hardpan formed by the clay soils to the abundant ground water beneath. Leaching upward through the fissures, the water attracts animals, which paw in the resulting puddles, making them deeper. They are deepened still further when the hippo and buffalo that come there to roll and wallow carry away a thick coat of mud, and eventually a small pan is created. However, the pan's size is limited; if it gets too big, then erosion of the surrounding land during the rains will silt it up again.

In a dead tree perched a motley selection of large birds: a fish eagle and a black-headed heron, two juvenile saddle-billed storks, and a huge gymnogene or "harrier hawk", with a bare, vulturine lemon-yellow face, that went off in strange weary flight through the bony trees. Beside the pool lay a full-grown lion with full belly and no manc; he got up slowly and moved away, displaying no haste until 1 jumped out of the Land Rover to get a look at the departing gymnogene. Apparently these maneless lions are rather common in this part of the Selous, and Brian recounted other anomalies of the region. The roan antelope, ostrich, and dik-dik, which are typical species throughout northern Tanzania, are entirely absent from the Selous. The silver-backed jackal has only been recorded three or four times, always near this eastern border, although it is common enough around the settlements outside the boundaries; yet in the Serengeti it is abundant even in areas well away from human settlements. Besides the giraffe found north of the Rufiji, and the puku, a swamp antelope confined to the lower Kilombero, the cheetah is also scarce and localized even on this hardpan plain of the eastern Selous; because of the scarcity of the open country that its usual hunting technique requires, the cheetah has apparently adapted to the prevalence of heavy cover by learning to stalk baboons as leopards do.

The behavior of a widespread species may vary greatly from place to place - for example, crocodiles are much more dangerous in some places than in others (probably according to the availability of fish), and the chimpanzees of Kibale Forest, in Uganda, have not been seen to attack and kill other creatures, as they do at Gombe Stream here in Tanzania, and also in West Africa. Nicholson was always suspicious of scientists at the Serengeti Research Institute who tended to "write up animal behavior on the basis of the Serengeti only, when areas like the Selous were far more typical. All those boffins with their great pulsating brains.

PETER MATTHIESSEN

selecting facts to fit their precious theories! Years ago, some S.R.I, people wanted to come down to the Selous. I said, fine, on three conditions. First, they must work on projects helpful to the Selous - for example, we needed more information on sable and kudu, and we still do; we don't need to know how high a vulture can fly. Next, that they go out on their research safaris in the rains as well as in fair weather, because animal behavior in the rains is a necessary part of the whole picture. Fmally, they were not to go to Dar more than once every three months. I never heard from any of them again." This sort of resentment against the field biologists who come into an area and instruct the old-time wardens about their wildlife is heard rather commonly in East African wildlife circles, but Brian Nicholson is better qualified to speak out this way than most: twenty-five years ago, he published a pioneering paper on wild elephant behavior which led the way for the formal studies that came later and is still highly regarded by students of Loxodonta afhcana} Because of the early end to his education, and because it pleases him to appear rough-hewn, Brian camouflages his ideas behind phrases such as "so to speak", "as you might put it", and "if that's the word", but in fact he is very articulate indeed.

On the track ahead, a Gabon nightjar fluttered up like a large chestnut-and-gold moth, only to alight just yards away and vanish in the dry season's brown leaves. A pygmy mongoose, quick and rufous, scampered like a huge shrew across the track, then some striped ground squirrels, long thin tails carried upright and waving slightly to one side, and a troop of yellow baboon, less burly than their olive cousins in the north. Where a new flush of green had arisen from the burnt-out black was a herd of Nyasa wildebeest, larger, paler, and more handsome than the race on the north side of the Rufiji, with roan flanks and haunches where that animal is gray, and a remarkable white blaze across the forehead. Further west, in the miomho, a fine big civet cat, started from a clump of tawny grass by the tires of the Land Rover, moved away a little distance before stopping to turn and have a look at us. The civet was black-faced, lustrous in the sere pale grass, averting its head just a little, the better to listen, and going on again when it heard no more than the soft vibration of the motor. The civet is not a cat at all but a large omnivorous weasel, a relative of the mongoose and the honey badger. It eats fruit and carrion as well as small animals and birds, and helps to propagate the fruit trees which it frequents by depositing their seeds in the defecation place that it returns to again and again, sometimes for years; there the seeds thrive, not only because of the powerful fertilizer but because the small rodents that normally eat up the fallen seeds avoid the civet smell and leave the tree nurseries alone.^

A group of buffalo went rocking away through the small trees; a lone hyena sat up like a sphinx. On the savanna as well as in the open woods there were impala, which seem to occupy the ecological niches filled

SAND RIVERS

further north by the gazelles; in the Selous, the impala is the major prey of the wild dog and the scarce cheetah. In the long grass of the miombo, these elegant antelope have the kongoni habit of climbing on to ruined termite mounds in order to see better.

The alluvial hardpan of this eastern boundary region (the hardpan is formed by river clays mixed with old sand washed down out of the eroded soils of the miombo] is characterized by terminalia thorn bush; lacking the ground water that is found in most of the Selous, the land depends for its water on the rivers and also the clay-bottomed pans that sometimes hold water throughout the dry season. With Hugo van Lawick, I spent a day at a large pan called Namakambari, or the Catfish Pool, an harmonious place set about with terminalia, albizzia, and combretum, and also small black cassia trees in yellow blossom. Here a hundred-odd hippo were in residence, but as the dry season^progressed and the pool shrank they would retire to the rivers and the last deep holes in the Kingupira Forest. The water lettuce at Namakambari had been stomped to a green mat by the hippos (which eat very little aquatic vegetation), and the place was a natural illustration of why most borehole wells created artificially for animals, both wild and domestic, turn out to be such ecological disasters: the grass and grot5nd cover were obliterated by the pressure of all the animals using the pool, and the packed earth, baked hard as brown concrete, extended as far back into the bush as I could walk without losing my grasp of the myriad game trails and becoming lost. In the green rim of trampled lettuce, a small company of waders picked silently along the margin: common and wood sandpiper, ruff, little stint and the three-banded plover with its coral bill - the only one of this far-flung group that makes its nest in Africa. There was just one individual of each species, and probably these birds were not early autumn migrants from Eurasia but a makeshift community of those left behind by the northward migrations of the spring before.