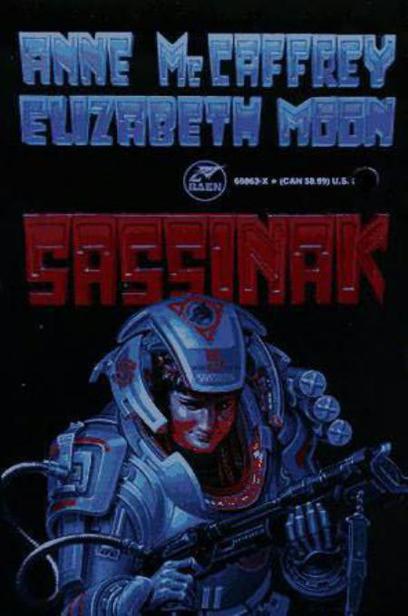

Sassinak

Authors: Anne McCaffrey,Elizabeth Moon

Planet Pirates I

Anne Mccaffrey

and

Elizabeth Moon

Table of Contents

BOOK ONEChapter OneBOOK TWO

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter FourChapter FiveBOOK THREE

Chapter Six

Chapter SevenChapter EightBOOK FOUR

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter ThirteenChapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

BOOK ONE

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1990 by Bill Fawcett & Associates

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

260 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10001

ISBN: 0-671-69863-X

ISBN: 978-0-671-69863-8

Cover art by Stephen Hickman

First printing, March 1990

Distributed by

SIMON & SCHUSTER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N.Y. 10020

Printed in the United States of America

Chapter One

By the time anyone noticed that the carrier was overdue, no one cared. Celebrations had started two local days before, when the last crawler train came in from Zeebin. Sassinak, along with the rest of her middle school, had met that train, helped offload the canisters of personal-grade cargo, and then wandered through the crowded streets.

Last year she'd been too young—barely—for such freedom. Even now, she flinched a little from the noise and confusion. The City tripled in population for the week or so of celebration when the orecarriers came in. Every farmer, miner, crawler-train tech or engineer—everyone who possibly could, and some who shouldn't have—came to The City. It almost seemed to deserve the name, with crowds bustling between the rows of one-story prefab buildings that served the young colony as housing, storage, and manufacturing space. Sassinak could pretend she was on the outskirts of a

real

city, and the taller dome and blockhouse of the original settlement, could, with imagination, stand for the great soaring buildings she hoped one day to visit, on the worlds she'd heard about in school.

She caught sight of a school patch ahead of her, and recognized Caris's new (and slightly ridiculous) hairdo. Shoving between two meandering miners, who seemed disposed to slow down at every doorway, Sassinak grabbed her friend's elbow. Caris whirled.

"Don't you—! Oh, Sass, you idiot. I thought you were—"

"A drunken miner. Sure." Arm in arm with Caris, Sassinak felt safer—and slightly more adult. She gave Caris a sidelong look, and Caris smirked back. They broke into a hip-swaying parody of the lead holovid's "Carin Coldae—Adventurer Extraordinary" and sang a snatch of the theme song. Someone hooted, behind them, and they broke into a run. Across the street, a familiar voice yelled "There go the skeleton twins" and they ran faster.

"Sinder," Caris said a block or so later, when they'd slowed down, "is a planetary snarp."

"Planetary nothing. Stellar snarp." Sassinak glowered at her friend. They were both long and lanky, and they'd heard as much of Sinder's skeleton twin joke as anyone could rightly stand.

"Interstellar." Caris always had to have the last word, Sassinak thought. It might not be right, but it was last.

"We're not going to think about Sinder." Sassinak wormed her fingers through the tangle of things in her jacket pocket and pulled out her credit ring. "We've got money to spend . . ."

"And you're my friend!" Caris laughed and shoved her gently toward the nearest food booth.

By the next day, the streets were too rowdy for youngsters, Sassinak's parents insisted. She tried to argue that she was no longer a youngster, but got nowhere. She was sure it had something to do with her mother's need for a babysitter, and the adult-only party in the block recreation center. Caris came over, which made it slightly better. Caris got along better with six-year-old Lunzie than Sass did, and that meant Sass could read stories to "the baby": Januk, now just over three. If Januk hadn't managed to spill three-months' worth of sugar ration while they were trying to make cookies from scratch, it might have been a fairly good day after all. Caris scooped most of the sugar back into the canister, but Sass was afraid her mother would notice the brown specks in it.

"It's just spice," Caris said firmly.

"Yes, but—" Sassinak wrinkled her nose. "What's that? Oh . . . dear." The cookies were not quite burnt, but she was sure they wouldn't make up for the spilled sugar. No hope that Lunzie wouldn't mention it, either—she was at that age, Sass thought, when having finally figured out the difference between telling a story and telling the truth, she wanted to let everyone know. Lunzie prefaced most talebearing with a loud "I'm telling the truth, now: I really am" which Sass found unbearable. It didn't help to be told that she herself had once, at about age five, scolded the Block Coordinator for using a polite euphemism at the table. "The right word is 'castrated'," was what everyone said she'd said. Sass didn't believe it. She would never, in her entire life, no matter how early, have said something like that right out loud at the table. Now she cleaned up the cookcorner, saving what grains of sugar looked fairly clean, and wondered when she could insist that Lunzie and Januk go to bed.

"Eight days." The captain grinned at the pilot. "Eight days should be enough. For most of it anyway. Aren't we lucky that the carrier's late." They both laughed; it was an old joke for them, and a mystery for everyone else, how they could turn up handily when other ships were "late."

"We don't want to leave witnesses."

"No. But we may want to leave evidence . . . of a sort." The captain grinned, and the pilot nodded. Evidence implicating someone else. "Now—if those fools down there aren't drunk out of their wits, anticipating the carrier's arrival, I'm a shifter. We should be able to fake the contact, unless they speak some outlandish gabble. Let's see . . ." He scrolled through the directory information and shook his head. "No problem. Neo-Gaesh, and that's Orlen's birthtongue."

"He's from here?"

"No, the colonists here are from Innish-Ire, and Orlen's from Innish Outer Station. Same difference; same language and dialect. New colony—they won't have diverged that much."

"But the kids—they'll speak Standard?"

"FSP rules: they have to, by age eight. All colonies provided with tapes and cubes for the creches. We shouldn't have any problem."

Orlen, summoned to the bridge, muttered a string of things the captain hoped were Neo-Gaesh, and opened communications with the planet's main spaceport. For all the captain could tell, the mishmash of syllables coming back was exactly the same, only longer. Hardly a language at all, he thought, smug in his own heritage of properly crisp and tonal Chinese. He spoke Standard as well, and two other related tongues.

"They say they can't match our ID to the files," Orlen said, this time in Standard, interrupting that chain of thought.

"Tell 'em they're drunk and incompetent," said the captain.

"I did. I told them they had the wrong cube in the lock, an out-of-date directory entry, and no more intelligence than a cabbage, and they've gone to try again. But they won't turn on the grid until we match."

The pilot cleared his throat, not quite an interruption, and the captain looked at him. "We could jam our code into their computer . . ." he offered.

"Not here. Colony's too new; they've got the internal checks. No, we're going down, but keep talking, Orlen. If we can hold them off just a bit too long, we won't have to worry about their serious defenses. Such as they are."

In the assault capsules, the troops waited. Motley armor, stolen from a dozen different captured ships and minor bases, mixed weaponry of all manufactures, they lacked only the romance once associated with the concept of pirate. These were muggers, gangsters, two steps down from mercenaries and well aware of the price of failure. The Federation of Sentient Planets would not torture, rarely executed . . . but the thought of being whited, mindcleaned, and turned into obedient and useful workers . . . that was torture enough. So they had discipline, of a sort, and loyalty, of a sort, and were obedient, within limits to those who ruled the ship or hired it. On some worlds they passed as Free Trader's Guards.

Orlen's accusations had not been far wrong. When the last crawler train came in, everyone relaxed until the ore carriers arrived. The Spaceport Senior Technician was supposed to stay alert, on watch, but with the new outer beacon to signal and take care of first contact, why bother? It had been a long, long year, 460 days, and what harm in a little nip of something to warm the heart? One nip led to another. When the inner beacon, unanswered, tripped the relays that set every light in the control rooms blinking in disorienting random patterns, his first thought was that he'd simply missed the outer beacon signal. He'd finally found the combination of control buttons that turned the lights on steady, and shushed the excited (and none too sober) little crowd that had come in to see what happened. And having a friendly voice speaking Neo-Gaesh on the other end of the comm link only added to the confusion. He'd tried to say he could speak Standard well enough (not sure if he'd been too drunk to answer a hail in Standard earlier), but it came out tangled. And so on, and so on, and it was only stubborness that kept him from turning on the grid when the ship's ID scan didn't match the record books. Damned sobersides spacemen, out there in the stars with nothing to do but sneak up on honest men trying to have a little fun—why should he do them a favor? Let 'em match their own ship up, or come in without the grid beacons on, if that's the game they wanted to play. He put the computer on a search loop, and took another little nip.

The computer's override warning buzz woke him again. The ship was much closer, just over the horizon, low, coming in on a landing pattern . . . and it was red-flagged. Pirate! he thought muzzily. It's a pirate. It can't be . . . but the computer, not fooled, and not having been stopped by the override sequence he was too drunk to key in, turned on full alarms, all over the building and the city. And the speech synthesizer, in a warm, friendly, calm female voice, said, "Attention. Attention. Vessel approaching has been identified as dangerous. Attention. Attention . . ."

But by then it was far too late.

Sassinak and Caris had eaten the last of the overbrowned cookies, and were well into the kind of long-after-midnight conversation they preferred. Lunzie grunted and tossed on her pallet; Januk sprawled bonelessly on his, looking, as Caris said, like something tossed up from the sea. "Little kids aren't human," said Sass, winding a strand of dark hair around her finger. "They're all alien, shapechangers like those Wefts you read about, and then turn human at—" She thought a moment. "Eleven or so."

"Eleven! You were eleven last year; I was. I was human . . ."

"Ha." Sass grinned, and watched Caris. "I wasn't human. I was special. Different—"

"You've always been different." Caris rolled away from Sass's slap. "Don't hit me; you know it. You like it. You would be alien if you could."

"I would be off this planet if I could," said Sass, serious for a moment. "Eight more years before I can even apply—aggh!"

"To do what?"

"Anything. No, not anything. Something—" her hands waved, describing arcs and whorls of excitement, adventure, marvels in the vast and mysterious distance of time and space.

"Umm. I'll take biotech training and a lifetime spent figuring out how to insert genes for correctly handed proteins in our native fishlife." Caris wrinkled her nose. "You're not going to leave, Sass. This is the frontier. This is where the excitement is. Right here."

"Eating

fish

? Eating lifeforms?"

Caris shrugged. "I'm not devout. Those fins in the ocean aren't sentient, we know that much, and they could give us cheap, easy protein. Personally, I'm tired of gruel and beans, and since we have to fiddle with their genes, too, why not fishlife?"

Sassinak gave her a long look. True, lots of the frontier settlers weren't devout, and didn't find anything but a burdensome rule in the FSP strictures about eating meat. But she herself—she shivered a little, thinking of a finny wriggling in her throat. Something wailed, in the distance, and she shivered again. Then the houselights brightened and dimmed abruptly.

"Storm?" asked Caris. The lights blinked, now quickly, now slow. From the terminal in the other room came an odd sort of voice, something Sass had never heard before.

"Attention. Attention . . ."

The girls stared at each other, shocked for an endless instant into complete stillness. Then Caris leaped for the door, and Sass caught her arm.