Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (29 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

The widespread cynicism about the quality of Italian justice was not without cause. The partisans in northern Italy had already witnessed the sort of purge they could expect by watching what had happened in the south of the country over the previous eighteen months. Here, under the tainted leadership of Pietro Badoglio, former Fascists continued to rule at every level of society. In some areas the Allies had insisted on ejecting Fascists from their posts – but many of these had been reinstated as soon as control of the liberated areas was returned to the Italian authorities. Policemen continued to harass Communists, and indeed anyone with overtly left-wing sympathies, and the singing of Fascist anthems in public remained fairly commonplace. In 1944 there was something of a Fascist revival in parts of Calabria, and even a brief spate of Fascist terrorism and sabotage. More than a year after their liberation, many communities in southern Italy were still being run by the same mayors, police chiefs and landowners, who used the same violent and repressive measures to oppress them as they had done during the Fascist years.

27

By the time the north of the country was liberated, the failure of the purge in the south was already well established. The problem was that to be a Fascist per se was never considered a crime – it could not be, since the Fascist government in Italy had been internationally recognized as legitimate since long before the war. In the north, however, things were slightly different. Here the Fascists, now based at Salò, had imposed their government upon the people despite the fact that they had been removed from power in 1943. More importantly, they had supported and facilitated the German occupation of their country. As a consequence, anyone who had held a position of authority in the Salò Republic could potentially be prosecuted both as a Fascist and as a collaborator.

On the face of it, the prospects for a proper purge in the north of Italy looked much more promising than they had done in the south. In practice, however, the political will to bring about such a change was missing from the start. When the Allies arrived, many officials and civil servants successfully pleaded their case to remain in office: in the chaos of the liberation their experience would be needed if the situation was ever to be brought under control. Likewise, many policemen and carabinieri (military police) were kept on because the Allies were understandably nervous about handing police powers over to the partisans. Businesses that had collaborated were allowed to keep trading, so as to avoid destroying workers’ jobs, and their owners and managers were kept in place for fear of further damaging the economy. In fact, apart from in those areas where the partisans

imposed

change, the default position was to keep the current power structures in place.

The purge, when it came, was delegated to the courts – but no real attempt was made to reform the legal system first. Despite calls for new laws, new courts, new judges and legal professionals, the general atmosphere within the legal structure was one of continuity rather than change. Some new laws were enacted, but the Fascist Penal Code of 1930 was not repealed – indeed it is still in use today. New courts were set up to hear cases of collaboration – the Extraordinary Courts of Assize – but these were generally staffed by the same judges and lawyers who had served under Mussolini. Thus many collaborators who went to court in Italy found themselves in the absurd situation where they were being tried by men who were at least as guilty as they were. Their sentences, when they were not acquitted, were scandalously lenient – judges simply could not enforce sanctions against other civil servants without also bringing their own roles into question.

28

For all their faults, the Extraordinary Courts of Assize did at least condemn crimes of violence, such as the murder or torture of civilians by the infamous Black Brigades. But even these sentences could be overturned by appealing to the highest court in Italy, the Court of Cassation in Rome. The judges who served in this court were unashamedly close to fascism, and apparently keen to defend the actions of the previous regime. By continually annulling the sentences handed down by the Assize Courts, and by pardoning, ignoring and covering up some of the worst atrocities committed by the Black Brigades, the Court of Cassation systematically undermined all attempts to bring Fascist criminals to justice.

29

Within a year of the end of the war the official purge had become something of a farce. Of the 394,000 government employees investigated up to February 1946 only 1,580 were dismissed, and the majority of these would soon get their jobs back. Of the 50,000 Fascists imprisoned in Italy, only a very small minority spent much actual time in jail: in the summer of 1946 all prison sentences under five years were cancelled, and the prisoners set free. Despite having witnessed some of the worst atrocities in western Europe, Italian courts handed out proportionally fewer death sentences than any other western European country - no more than ninety-two out of a postwar population of more than 45 million. This is twenty times fewer executions per head than in France.

30

Unlike their German partners, no Italian was ever brought to trial for war crimes committed outside Italy.

In the face of such a spectacular failure of justice, it is unsurprising that popular frustrations began to resurface. Once people had concluded that any purge was impossible if left to the authorities, it was only a short step to deciding to take the law back into their own hands. In the months after the end of the war a second wave of popular violence swept parts of the country, as people demonstrated their distrust of the official purge by breaking into prisons and lynching the prisoners there. This occurred in towns across the provinces of Emilia-Romagna and Veneto, but also in other northern regions.

31

The most famous instance was at Schio, in the province of Vicenza, where former partisans broke into the local prison and massacred fifty-five of its inmates. The words of some of the people who were present during this crime show how bitterly the people resented the failure of the purge at the time. ‘If only they had held two or three trials,’ claimed one, ‘if only they had tried to do something, it might have been enough to release the tension that was felt by the people.’ ‘I have always defended the act,’ claimed another, when interviewed more than fifty years later, ‘because for me it was an act of justice that they were killed … I have no compassion for those people, even if they are dead.’

32

The Failure of the Purge Across Europe

The Italian experience was an extreme example of something that occurred all over western Europe. The postwar purges were at least a partial failure everywhere. In France, for example, praised by the Allies for the ‘thoroughness’ and ‘competence’ of its purge, disillusionment with the courts was widespread.

33

Of more than 311,000 cases that were investigated in France only about 95,000 resulted in any kind of punishment at all — just 30 per cent of the total. Less than half of these - only 45,000 people – received a prison sentence or worse. The most common punishment was the loss of civil rights, such as the right to vote, or the right to be employed in any kind of public office. However, most of these punishments were reversed after an amnesty in 1947, and the majority of those imprisoned were set free. After a further amnesty in 195 I only 1,500 of the worst war criminals remained in prison. Of the 11,000 civil servants who were removed from their jobs in the first days of the purge, most of them were back at their posts within the next six years.

34

Half of those punished in Holland suffered only the removal of their voting rights, and while most of the other half were imprisoned, their sentences were generally short. In Belgium the punishments were slightly harsher, with 48,000 prison sentences being handed out, 2,340 of them for life. But this still only represented about 12 per cent of the total number of cases investigated. Belgian judges also gave out 2,940 death sentences, but of these all but 242 were commuted.

35

Many people across the continent regarded such sentencing as hopelessly lenient. They certainly made their frustrations known. In May 1945 a series of demonstrations took place across Belgium in which collaborators were lynched, their families humiliated and their houses sacked.

36

In Denmark, where serious collaboration was almost unknown, some 10,000 people took to the streets of Aalborg to demand harsher treatment for collaborators, and a general strike was called. Smaller demonstrations occurred in other parts of the country.

37

In France, as in Italy, there were numerous attempts by mobs to break into prisons and lynch the inmates.

38

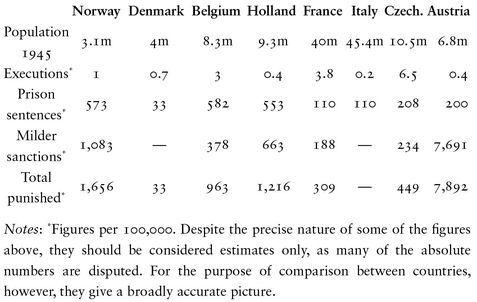

Perhaps the only place in north-west Europe where the people showed any satisfaction with the purge was Norway, where the trials were rapid and efficient, and the punishments harsh. Out of a population of just 3 million, 90,000 cases were investigated, and more than half of these received some kind of punishment. In other words, more than 1.6 per cent of the entire population was punished in some way after the war; and this does not include the unofficial punishments that were meted out on women and children, which shall be the subject of the next chapter.

39

The fact is that justice varied wildly from one nation to the next. The country where an individual was most likely to be investigated was, needless to say, Germany, where the denazification process necessarily demonized an entire people. More surprisingly, however, the country where an individual was most likely to be imprisoned was Belgium, with Norway coming close behind. The country where an individual was most likely to be executed was — just as surprisingly – Bulgaria, where more than 1,500 death sentences were carried out. (As in the rest of eastern Europe, however, many of these executions had more to do with the Communist seizure of power than with punishment for actual crimes.)

This discrepancy between the way collaborators were treated in different countries is perhaps best illustrated by what happened in central Europe. Austria and Czechoslovakia, though neighbours, had vastly differing results to their respective purges. In Austria, collaboration was overwhelmingly treated as a minor crime, to be punished with fines or the loss of civil rights. More than half a million people were punished in this way. These sanctions would not last long, however: in April 1948 an amnesty restored civil rights to 487,000 former Nazis, and the rest were allowed back into the fold in 1956. Some 70,000 civil servants were dismissed but, as in other countries, their exit proved to be via something of a revolving door.

40

In the Czech lands, by contrast, collaboration was taken much more seriously. The Czech courts handed out 723 death sentences for crimes committed during the war, and because of their unique policy of conducting executions within three hours of the sentence, a higher percentage were actually carried out here than anywhere else in Europe – almost 95 per cent, or 686 in all. While the absolute number of executions does not appear much worse than, say, France, one must remember that the Czech lands had only a quarter of France’s population - their execution rate was therefore four times that of France’s. Czechs were twice as likely to be executed for collaboration as Belgians, six times as likely as Norwegians, and eight times as likely as their Slovak cousins in the eastern half of the country. But the comparison with Austria is most telling of all. Of the forty-three death sentences in Austria, only thirty were ever carried out, making Austria one of the safest places in Europe for collaborators. Czechs were over sixteen times more likely to be executed for ‘war crimes’ than their Austrian neighbours.

Of course, there are all kinds of cultural, political and ethnic reasons for the differences between these two countries. The Czechs wanted revenge for the dismemberment of their country, and their marginalization by the German minority in their midst – a minority that they were in the process of expelling, even while the trials were going on. The Austrians, by contrast, had largely welcomed the

Anschluss

in 1938, and felt a natural affinity with their fellow German-speakers – all of which made a mockery of their official status as Hitler’s ‘first victim’. It was precisely

because

Austrian collaboration had been so universal that the authorities felt unable to punish it properly.

Whether the difference between the way collaborators were treated in the two countries was

fair

or not is a completely different matter. From an international viewpoint it is impossible simultaneously to justify the severity in one and the leniency in the other.

Table 2: The judicial punishment of collaborators in western Europe

41