Savant (18 page)

Rosa was permanently on-screen on the Service Floor of Lima College. Workstation 3 had been tracking her for her entire College career. She had displayed erratic behaviour, via the screen, for two hours after she first received Tobe’s data, and her station had gone to Code Green, but this was not considered unusual for Master Rosa, and Service had stepped down to Code Blue, overnight.

Gilles in Winnipeg had also exhibited problematic behaviour within hours of receiving Tobe’s data, and Service had given him a Code Green, but his status had ramped-up, again, when his Assistant and Companion had alerted Service that they considered him to be in a dangerous state of mind.

Gilles was in the infirmary in Winnipeg, where Medtech was trying to unravel the problems.

Tobe’s data was already out in the World, so a file, exactly the same as Pitu’s was compiled for him, and two more for his Assistant and Companion.

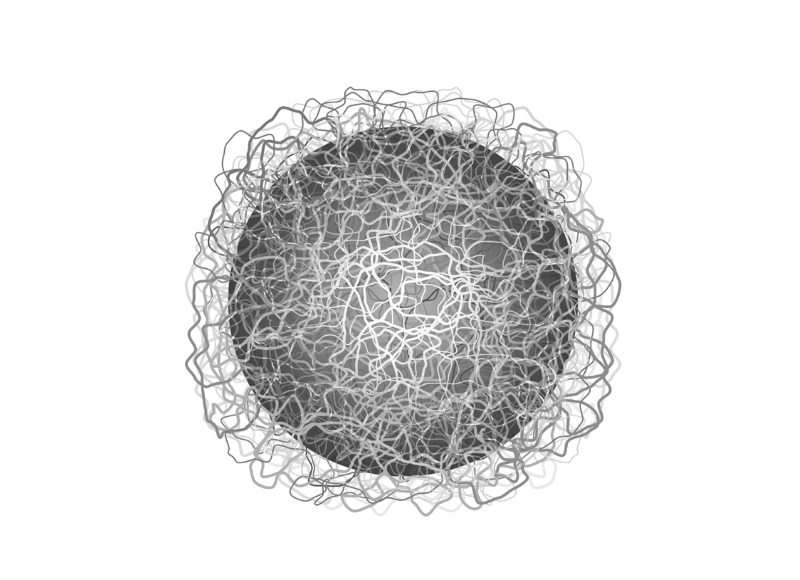

Workstation 5 on the Service Floor in Winnipeg was switched out to monitor Gilles’s Assistant when his turn came around. At the switch-out, Esau’s screen was showing a strong blue sphere of threads, which throbbed rhythmically, and glowed in places, but had a limited corona. Named Operator Blackwater noticed an anomaly at 70, 67, about an hour into monitoring.

“Reset zoom to 70, 67,” said Blackwater, rolling the sphere left and right in decreasing increments. The screen zoomed in, and the threads of light began to look like pieces of string, woven with various shades of blue, in a tangled mass.

Blackwater reached his left hand out to touch Operator Turner. There was silence as Blackwater rolled the palm-sized, rubberpro sphere again. A length of thread came into sharp focus. It was grey and fraying, a pale imitation among the stronger blue lengths of thread.

“Anomaly at sector 70,” said Blackwater, hitting a button. “Tone sent.” The screen in front of him blinked, and Turner tensed.

“It’s in the emotional range,” said Turner.

“We should check it anyway,” said Blackwater. “What’s the precedent?”

“Tech?”

A Tech appeared from the racks at the centre of the Service Floor, which was almost identical to the one that was monitoring Pitu, and anyone else that had seen into Tobe’s room.

“We need authorisation for emotional response data on an intellectual line-check.”

“Skip it,” said Blackwater, not turning from his screen. An overlay was coming up on the left hand side of the screen. It read, ‘Clearance for emotional response data within the parameters of the intellect sweep is granted automatically, at the discretion of the monitoring Operator’.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

T

OBE WAS SITTING

on his stool at the kitchen counter, while Metoo moved around him, clearing away his dishes. When she had finished, she sat at the counter opposite him.

“Tobe,” said Metoo, “you can’t go to the office today.”

“Tobe always goes to the office, except on rest days.”

“Service messed up, and you need to have another rest day,” said Metoo, hoping that it would be enough, but knowing that it wouldn’t.

“Yesterday was a rest day, because... Why was yesterday a rest day? What day is it? Why can’t Tobe go to the office? Let Tobe go to the office.”

“It’s not up to me,” said Metoo, avoiding answering too many questions in the hope that Tobe might forget that he’d asked them.

“Metoo sends Tobe to the office. It is up to Metoo.”

“No. It’s Service, remember?”

“Service is gone.”

“No. Service is still there, but they talk to me, now, instead of talking to you.”

“Tell them, Tobe is going to the office, today.”

“It doesn’t work like that. There is something they want you to do, though.” She hoped that taking a different tack might help.

“Tobe always works in the office. What is the probability of Tobe working in the office?”

“But you worked here, in your room, yesterday,” said Metoo, smiling, and trying to keep the conversation manageable, and light.

“A black swan,” said Tobe, apparently deep in thought for a moment. “They used to call it a black swan. Probability.”

“Probability,” said Metoo.

“They want Tobe to do more probability?”

“No. They want you to answer some questions.”

“Tobe’s job is to answer questions, find solutions, work out the maths for things. Tobe is always trying to answer questions.”

“Not those sorts of questions, other sorts.”

“Other sorts? What other questions? Who wants to ask Tobe questions?”

“Well, could I ask you some questions?”

“‘Could I ask you some questions?’ That’s a question.” Tobe chuckled low in his chest, and looked over Metoo’s shoulder, apparently into space. His head tipped back slightly, and he closed his eyes and began to murmur.

Metoo reached across the kitchen counter, and took Tobe’s face in her hands. He dropped his head to a front-facing position and opened his eyes.

“May I ask you some questions?” asked Metoo.

“‘May I ask you some questions?’ That is asking Tobe a question.”

“And what is Tobe’s answer?”

“That is a question, too.”

“I’m going to ask you some questions, now,” said Metoo, smiling slightly, knowing that Tobe might be a genius, but he was a genius with limitations.

A

T

06:00 G

OODMAN’S

screen switched out. The swirl of bright blue was like a shoal of fish with one mind, weaving a tight figure-of-eight with a throbbing halo, and flashing silver strands.

“Wow!” said Chen.

“Wow indeed,” said Bob.

“You don’t seem surprised.”

“This was the one thing they did tell me. How else do you think they got me out of a Rest period after only six hours?”

“You know who this is?”

“Not who, but I do know what.”

“Line-check?”

“I think it’s better if we just observe, for now. Did you ever see anything like this in your life?”

“Did anyone?”

The figure-of-eight pulsed and throbbed in its rhythmic electric-blue and silver patterns for a few minutes, mesmerising Goodman and Chen.

At 06:03, Chen asked again, “Line-check?”

“Patience.”

“Bob, what are the rules and regs for the first line-check after a switch-out?”

“It’s your signature on this machine,” said Bob, “I’m just the jockey, so, if you want a line-check, you should order a line-check. I’m just feeling my way, here.”

They sat in silence for a few more moments as the shoal shimmered across the screen, its electrifying halo throbbing ceaselessly at them. It was the most alive entity that Bob Goodman had ever seen on screen, and he’d seen a lot of screen. He could retire after seeing this.

At 06:04 Chen asked, “So what do you think?”

Bob made an odd noise in his throat that sounded like a half-cough, half-sigh.

“‘The first line-check should be completed at switch-out, but’, and here’s the interesting bit, ‘should be completed within fifteen minutes of the switch-out’. Tell me, Chen, how long does it take me to do a line-check?”

“On this screen?”

“I take your point,” said Goodman, his hand closing over the rubberpro sphere on the scuffed counter-top of Workstation 7.

At 06:05 the screen at station 7 glowed bright white, and the shoal of thready particles formed a sparkling silver sphere, reflecting light like a sequin-covered globe or a mirror ball.

“Okay,” Chen managed to say without actually closing her mouth. “Okay, now it really is time for a line-check.”

“Too late,” said Bob Goodman, pushing his chair away from the counter and beaming. He planted his feet firmly on the floor, still sitting, and twisted his body, sending his chair spinning as he thrust his fists into the air.

“Bob? Bob...” said Chen.

M

ASTER

M

OHAMMAD WOKE

up to a new day, in Tunis, ready to get back to work on the data that he had received from Tobe. There had been no further communications or explanations.

His Assistant, Yousef, and his Companion, Sabah, ate breakfast with him, looking out of the kitchen window, across the College, with its towers and minarets piercing the early morning skyline.

“It is so beautiful today,” said Sabah.

“Probability,” said Mohammad.

“Has no memory,” said Yousef.

“It is like a mantra with you, Yousef,” said Sabah.

“If it is good enough for Eustache, it is good enough for me,” said Yousef.

Mohammad looked down into his dish of oatpro and dates. He liked to listen to his Companion and his Assistant playing these verbal games, like he enjoyed listening to the birds singing, or the call to prayer. He had no way to decipher the sounds. He had a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand ways to decipher numbers and decrypt mathematical symbols. Maths was his music and his linguistics, and the babbling of his brook.

“Probability,” said Mohammad, again.

“He will have me tossing a coin all day long,” Yousef said to Sabah, “and then he will have me toss a different coin, lest the coin I tossed be unbalanced. It is the weight of his mind that is unbalanced.”

“And yours is perfectly balanced, I suppose?” asked Sabah, laughing. “You feeble-minded men with your left brain this and your right brain that, and your probability. I know my Eustache too, and I’d sooner watch a cat swinging from a pendulum and call it ‘Foucault’s Cat’.”

“Or ‘Schroedinger’s Pendulum’,” said Yousef.

“Our jokes are too old,” said Sabah, sighing.

“And too true,” said Yousef.

“Off with you,” said Sabah, picking up Mohammad’s dish, and stacking it inside Yousef’s. Go to your play, and stay away until it is time to eat. I have things to do.”

W

ORKSTATION

4

AT

Tunis College was showing a glowing blue ball of threads, throbbing rhythmically, but calmly, in front of its Operator. The Service Floors of individual Colleges had not been alerted to the global problem, and it was one Operator one screen in Tunis. The atmosphere was as sultry as the day’s weather.

McBride began a line-check when he came on-station at 06:00. At 06:15 everything was normal.

I

N

M

UMBAI,

S

ANJEEV

was roused by his Companion. He bathed quickly, and efficiently, leaving his towel on the bathroom floor as he shook his robe on over his head. His Assistant ate breakfast with him, while his Companion watched over them. Saroj, the new Assistant, was very young, and Kamla felt like her older sister or aunt, watching out for her.

“Master Sanjeev, are we to review Master Tobe’s notes again, today?” asked Saroj.

“I think perhaps you might return to your own work, Master Sanjeev,” said Kamla. “Let Saroj take a look at Master Tobe’s musings, and put them into some sort of order before you review them again. They seem terribly taxing to me, and your own work should not be made to suffer, however notable Master Tobe might be.”

“I should like that,” said Master Sanjeev.

“Probability, after all, has no Master,” said Saroj. Then she laughed at her pun, burned with embarrassment and dropped her face, so that her Master could not see her.

“Saroj speaks wise words,” said Kamla, smiling, and happy to have got her way. “Perhaps Tobe will become the new Master of probability, but, in the meantime, you have work to discuss and share in the community, that is long past being ready. Spend this time more wisely, Master, I beg of you.”

Sanjeev looked up from his breakfast, perfectly willing to do the bidding of these two chattering women. He did not understand them, and he did not mean to. He only wanted to go to his office and work on his equations, and that was all that these women seemed to want for him. The new one had a lilting sing-song voice too, although most of what she said was totally incomprehensible to him.

O

PERATOR

P

ERRETT SAT

at Workstation 1 at Mumbai College. She keyed in her Morse signature, and pulled in her chair. She covered the rubberpro sphere with her left hand, and began her first line-check of the day. The ball of slightly throbbing light in front of her was a glorious shade of sky blue, not intense, but watery and beautiful. The colour was incredibly uniform, and there were no anomalies that could be seen by the naked eye. She completed the line-check anyway.

She had sat in front of this screen, four days a week, come High or Low, for four years, and she knew the subject like the back of her hand. She did not know his name, and probably never would, and she did not know his rank, although she had long-since guessed that he was a Master, probably in the sciences or maths.

Perrett had an uncanny knack with these things. She had been working station 1 since before it had been dedicated to this subject, and, although she had been relatively new to the job, then, with only two Lows under her belt, she had known that her subject had been changed. She had come back from her biennial sabbatical, but still, after six weeks, she recognised that her subject had been changed.