Save the Cat! (15 page)

Authors: Blake Snyder

The Real Happy Ending:

$IOO million in domestic

B.O.

Now that you know that it works, you'll start to see how these beats can apply to your script.

EXERCISES

1. Type up the BS2 and carry it with you everywhere. Whenever you have an idle moment, think about a favorite movie. Can the beats of that movie fit into neat, one-sentence descriptions of each of the 15 blanks?

2. Go back to Blockbuster (boy, are they tired of you by now) and check out the 6-12 movies in the genre of the movie you're writing. Sit and watch as the beats of these films are magically filled into the blanks of the BS2-

3. For extra credit, look at

Memento,

Yes, it's an entertaining movie; yes, it even falls into the category of genre "Dude with a Problem." Does it also match the beats of the BS2? Or is it just a gimmick that cannot be applied to any other movie? HINT: For all the hullabaloo surrounding

Memento,

guess how much it made?

And if you want to seriously debate the value of

Memento

in modern society, please go ahead and contact me at the e-mail address provided in Chapter One. But be ready for one hell of an argument from me!! I

know

how much

Memento

made.

If we are very lucky we find a guru. These are people we meet along the way that have more wisdom than we do and, to our surprise, offer to share what they know. Mike Cheda is the first guru I met in the screenwriting business and for 20 years he has continued to amaze me with his ability to spot, understand, and fix the problems of any screen story.

I first met Mike when he was head of development for Barry &. Enright. Mike also worked in that capacity for Disney and was VP of Development at HBO and Once Upon A Time Productions. Over the years, Mike has developed hundreds of movie and television projects — often from initial concept to final cut. He has not only been an executive for these and other companies, but is himself a writer (something more development execs should try) whose

Chill Factor

starred Cuba Gooding, Jr. and the Dash Riprock-named Skeet Ulrich.

No matter what incarnation Mike Cheda appears under — executive, writer, or producer — wherever he goes, his magic story touch is the stuff of legend. Of the many scalps on his belt, Mike is the guy credited with cracking the story for the Patrick Swayze movie,

Next of Kin.

Though it was a spec script purchase in the million-dollar range,

Next of Kin

had

problems that needed tweaking before it could get a green light — and it was Mike who solved them. Mike even showed me the

place

where this event occurred. One day we were taking a time-out from a story we were trying to break, bowed by despair and self-loathing over not knowing how. While walking through Century City, Mike stopped at the hallowed piece of sidewalk.

It was here, he said, Jacob Bronowski-like, during a similarly meditative walk when his brain was filled with all the wrong ways to fix

Next of Kin,

that he'd come up with the right way. "It just hit me. Cowboys and Indians!" And indeed when he presented this simple construct to the producers of

Next of Kin,

that's exactly what guided the rewrite. In the course of his career, Mike has had many such moments. Like some String Theory physicist, he is always working on perfecting his story skills — often in ways that seem otherworldly, but almost always prove to be inspired.

So when I ran into Mike recently and asked what new ideas he'd come up with, he pulled out an artist's sketchbook from his satchel and opened it with gleeful enthusiasm. The two halves of the sketchpad, its spiral binding running down the middle, offered a larger-than-normal field. Across both pages, he had drawn three straight lines, demarcating four horizontal rows. And in the middle of these four equal rows were cut-out squares of paper, each was a beat of the screen story he was working on.

"It's portable," Mike cackled like a mad scientist.

"Ah!" I said. "The Board."

And we both nodded with the respect.

The Board.

CHAIRMAN OF

THE

BOARD

The Board

is perhaps the most vital piece of equipment a screenwriter needs to have at his disposal — next to paper, pen, and lap-lop. And over the years, whenever I've walked into someone's office and seen one on the wall, I have to smile because I now know what it is — and the migraine-in-progress it denotes. Boards come in all types and sizes: blackboards smeared with chalk, cork boards with index cards and pushpins to hold the beats in place, and even pages of a yellow legal pad Scotch-taped to hotel walls while on location — in the attempt to re-work a script on the fly. The Board is universal. And yet of the screenwriting courses I know of, I've never really heard this useful tool discussed.

So damn it, let's talk about it!

I saw my first one on Mike Gheda's office wall at Barry & Enright 20 years ago.

Naif

that I was — though I'd already been paid actual money to write a few screenplays — I'd never seen The Board, nor could I imagine what it would possibly be used for. Didn't you simply

sit

down and

start

and let the scenes fall where they may? Didn't you just... let er rip?

That's what I always did.

But thanks to the Chairman of The Board, Mike Cheda, I learned not only the vital importance of planning a script by using The Board, but how to use it to supercharge my results. Since that time I have employed it often. In my case, I use a big corkboard that I can hang on the wall and stare at. I like to get a pack of index cards and a box of push pins and stick up my beats on The Board, and move em around at will. I have many decks of these index cards, rubber banded and filed by project, of scripts written and yet-to-be. And all I need to do to revisit any of these scripts is lake out the pack, deal 'em up on The Board, take a look to know where I left off— and figure out if I need to call Mike.

The Board is a way for you to "see" your movie before you start writing. It is a way to easily test different scenes, story arcs, ideas, bits of dialogue and story rhythms, and decide whether they work — or if they just plain suck. And though it is not really writing, and though your perfect plan may be totally abandoned in the white heat of actually executing your screenplay, it is on The Board where you can work out the kinks of the story before you start. It is your way to visualize a well-plotted movie, the one tool I know of that can help you build the perfect beast.

But here are the most beneficial things about The Board:

a. It's tactile and...

b. It wastes a

lot

of time!

The exercise of working The Board uses things other than your fingers on a keyboard. Pens, index cards, pushpins. All things you can touch, and see, and play with at will.

And did I mention how much

time

you can waste doing all this?

You can spend a whole afternoon at Staples picking out just the right-sized board. You can spend the next morning figuring out where it goes on your wall. You can even go mobile with the index cards. You can pop that deck in your pocket, head out to Starbucks, take the rubber band off, and sit there and shuffle your cards for hours, laying out scene sequences, set pieces, and whammies. It's great!

And the best part is, while you're doing all this seemingly ridiculous, time-wasting work, your story is seeping into your subconscious in a whole other way. Have a great piece of dialogue? Write it on a card and stick it on The Board where you think it might go. Have an idea for a chase sequence? Deal up them cards and take a looksee.

And talk about creating a pressure-free zone! No more blank pages. It's all just little bitty index card-sized pages. And who can't fill up an index card?

All well and good but how does it apply to

me?

you ask.

Me! Me! Me!

All right, let's talk about you and your Board.

FIRST CARDS FIRST

Once you've bought the size and type of board you feel most comfortable with, put it up on the wall and have a look. It's blank, isn't it? Now take three long strips of masking tape and make four equal rows. Or if you're more daring, use a magic marker instead. Either way it looks like this:

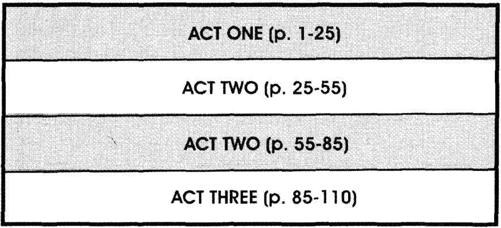

Row #1 is Act One (pages 1-25); row #2 represents the first half of Act Two up to the midpoint (25-55); row #3 is the midpoint to the Break into Act Three (55-85); and row #4 is Act Three to the movie's final image (85-110).

It looks so easy, doesn't it? Well, it is. That's the whole idea. And after a couple of go-rounds using this tool, it will start to feel familiar, too. Soon, like a slot car racetrack, the corners and open stretches of this imaginary concourse will become well-worn and pleasing geography.

You will quickly find that the ends of each row are the hinges of your story. The Break into Two, the midpoint, and the Break into Three are where the turns are; each appears at the end of rows 1, 2, and 3. To my mind, this fits my mental map of what a screenplay is perfectly. And if you buy Syd Field's premise that each of the turns spins the story in a new direction, you see exactly where it occurs.

Now in my hot little hand I also have a crisp, clean, brand new pack of index cards. (Oh, it's fun to unwrap the cellophane!) And now with the help of a fistful of Pentels (

not

a Clint Eastwood movie) and my box of multi-colored pushpins, I'm ready to put up my very first card. To waste as much time as possible, I usually neatly write the title of the movie on one such card and stick it up at the very top and take a step back. In a few weeks, or months, the Board is going to be covered with little bits of paper, arrows, color-coding, and cryptic messages. For now, it's clean.

Enjoy it while you can, lads.

Okay. Time to start.

Although you can write anything you want on these index cards, they are primarily used to denote scenes. By the time we're done, you'll have 40 of these — count em, 40 — and no more. But for now, in this rough stage, we'll hang loose. Use as many as you want. And if you run out, you get to go back to Staples and waste more time — so go for it!

What goes on your final 40 is very simple. Each card stands for a scene, so where does the scene take place? Is it an INTERIOR or an EXTERIOR? Is it a sequence of scenes like a chase that covers several locations? If you can see it, write it with a magic marker: INT. JOE'S APARTMENT - DAY. Each card should also include the basic action of the scene told in simple declarative sentences. "Mary tells Joe she wants a divorce." More specific information will be noted later. For now, the average beat or scene looks like this: