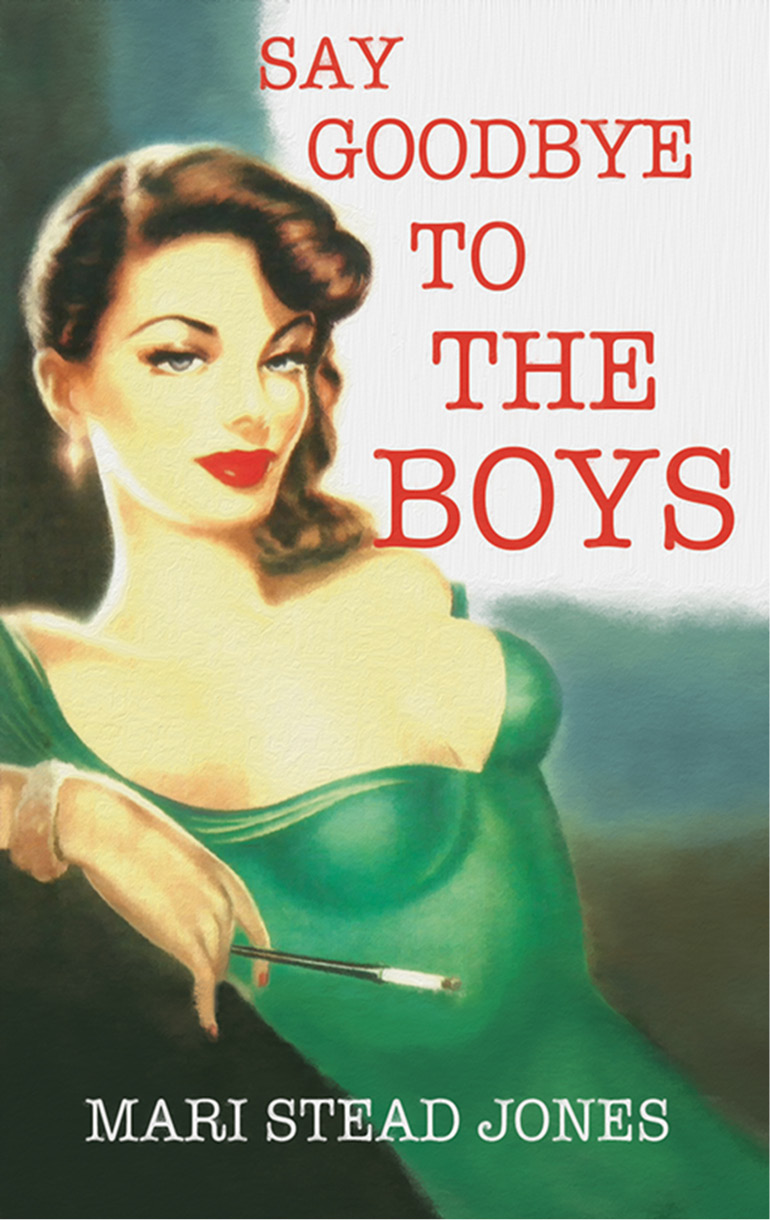

Say Goodbye to the Boys

Read Say Goodbye to the Boys Online

Authors: Mari Stead Jones

Author Bio

Â

Â

Â

Â

Mari Stead Jones was born in Preston and still lives in the north west of England. This is her first novel.

Dedication

Â

Â

Â

Â

For my father and my daughter

I

Â

Â

Â

Â

It was a good place to be, even with Laura standing at the foot of the bed delivering the Sunday morning sermon. It was the best of all possible places â father's house, 21 Liverpool Street, Maelgwyn-on-Sea, my old room above the kitchen at the back of the house, a church bell ringing in the town, and a blackbird in good voice in the yard outside. Even with a head full of beer and fags, a good place to be.

âDon't pretend you're asleep! What about your shoes for a start?' I stiffened under the sheets. I had socks on my feet. âWhat time did you crawl in this morning, I'd like to know? Smells like some old brewery in here. And you were such a refined little boy.' She prodded me. âToo ill to talk are we? Whatever were you thinking of â leaving your shoes there for all the world to see?'

My shoes! My demob shoes! Oh good God, I'd taken them off at the front door, hadn't I? Carried them upstairs hadn't I?

âFull of water, both of them! At least I think it's water. But what did the milkman think? And all the people on their way to chapel; what did they think? Don't tell me no lies boy! It was past three when you came in because it didn't start raining till half past. Not one wink of sleep have I had. Not one tiny wink. You left them in the rain, didn't you?' A long despairing sigh. She had moved to the window now, her voice husky with complaint. âYou know how I've been â ever since that old war started, not been able to sleep a night through.'

Quite mindless, had been my father's judgement on her â Laura Roberts, his second wife, my stepmother â quite mindless, but very kind. Now she was back at the side of the bed. âAnd you were such a good little boy, Philip. Talk to me.' Silence she couldn't bear. âWherever were you till that time? Why did you leave your shoes there for all the world to see?' For Laura all the world was Liverpool Street. âYou and those friends of yours...'

I sat up and pulled the sheet clear of my head.

âOh,' she cried out, âlook at your eyes! Debauchery, that's what you've got! How long is this going on for, Philip?'

Forever, I hoped. Forever and ever! Back home in the one good place, soldier from the wars returned. But that was before the days of madness and death.

Maelgwyn town was still and quiet and full of dusty sunlight that Sunday morning, echoes of hymns in the air. Liverpool Street was in the old town, near the Market Hall where my father had his shop. A neat, terraced street, not poor, not rich, with doorsteps making black, polished statements all the way along. My shoes, brimming with water, must have sent the chapel-going brows flapping. Once down the High Street the town changed, bricks and pebbledash and stucco replacing stone, and houses growing larger, taller, with rooms abounding, all the way to the sea front, and the Promenade. Yet it was here, in the newest, grandest part of town, that shabbiness showed. Peeling paint and flaking plaster, windows without curtains and empty houses, scars of war everywhere in spite of the fact that not a shot had been fired at it, not a bomb dropped. Here no visitors had arrived for six long summers. And here there had been a kind of occupation â by Civil Servants, by the Royal Air Force, by the Yanks. And the bruises showed.

âSome of them were animals,' Laura had told me. âNot all of them, mind. Burton was a very nice boy. Been to college and everything.' Burton had been a Lieutenant in the US Air Force. Burton had married my sister Gwen and taken her back to Baltimore. And anyone who had taken Gwen on must have been all right. Must have been a bloody saint too!

The wind was coming in off the sea. There were big ships out there whose dialogue of sirens you could hear, especially at night, all of them waiting for a tide to take them the last six miles up to the port. Maelgwyn-on-Sea the town wanted to be called, but it was on an estuary, and its beach was pebble and estuary mud, and dredging was a dirty word. You retired to Maelgwyn, and there were elderly men with elderly dogs at the water's edge to prove it. But now the barbed wire had gone. Only one concrete pillar box remained from the war, and there was talk of converting that into a public toilet. It seemed fitting.

Emlyn Morton waved from the deck of the

Ariadne

in response to my whistle. Yachts and fishermen's boats were strung in a line along a muddy river that ran parallel with the estuary before joining it at a break in the tall dunes. The

Ariadne

was the seventh boat along, a Liverpool Bay fisher, 39 feet long, 9 feet in the beam, which we had acquired and which we were doing up. In the

Ariadne

we were going to sail south one day. The master plan, according to Emlyn Rhys Morton.

The bow of the dinghy dug into the stinking black mud at the river's edge. I stepped aboard and Emlyn poled it out into the channel.

âI left my shoes on the front doorstep,' I told him.

âMarvellous,' he replied, âbloody marvellous.' He settled in the stern, sculling with one hand. How did he manage to look so neat, so tidy â even after crawling all over that boat? Dirt didn't stay on him. He had clothes that didn't wrinkle. And it had always been like that. I had known him all my life.

âDon't rock the bloody boat,' I said.

âGot a bad head, matey?' He leered at me. âKnow what it means? Blood pressure! It'll probably kill you before you're thirty.'

âIt's being so cheerful that keeps you going...'

âI'm talking facts. Your arteries are probably hardening prematurely. The next step is dizzy spells, then blackouts of increasing intensity, then a stroke. The long dive into oblivion; that's how you'll go. How many pints did you have?'

âIt's the fags, not the beer,' I replied.

Emlyn laughed. âDon't give me that. Heard it all before.' A great theorist, Emlyn Morton â especially on medical matters. âOh God my heart skipped a beat then! That's twice in the last hour. And I had the cramps last night â like a bloody contortionist in bed last night. Fucking killing ourselves â that's what we're doing.'

The dinghy bumped gently against the

Ariadne

's hull. We climbed aboard. âThis old cow's not so well this morning, either,' he said. âHad to pump her out. Leaking like a bucket down there.'

We sat on the roof of the cabin and surveyed

the debris on the deck. Throughout the war

the

Ariadne

had been on the beach, her planks shrinking, warping, parts of her looted by the town's beachcombers. We spent our days patching and caulking and painting, only to find new faults, new ruptures, new and rusty sores. âNo wonder they let us have her for fifteen quid,' Emlyn remarked, then added brightly, âbut we'll make something of her.' He stood and waved to a couple of fishermen as they rowed out to a mooring. Emlyn Morton was the most amiable character going. Always had been.

âWell,' he decided, âwe'll have to beach her tomorrow and give her a thorough going over.' He said it with relish. Another day of scraping and burning and caulking, the old boat propped up on that stinking, black mud.

But nothing got Emlyn Morton down. He had been like that at Jenkyn Pierce County School. I imagined that he had spent five years in the Air Force like that too. He was in a German camp for three of the years, but probably neat, composed, complaining mildly of his health and amiable even there. He'd picked up a Distinguished Flying Medal, although he wasn't sure what for and thought it didn't really matter anyway. They called his father the Rustler, because he had been, among other things, a dubious cattle dealer before he went bust. Only Emlyn and his father in that tall, dingy house in the Crescent now. A family that had known trouble. His mother, both his sisters dying of TB, and Idwal Morton half retired from life itself, a grey, remote man, full of shadows, with hands that trembled. Yet Emlyn came out of there each day fresh, alert, not a hair out of place, tiny and genial and with a smiling, school boy face.

We sat back and watched the gulls circle, the sun and the wind making new shades on the marram grass on the dune. I had dreamt of this place throughout the war, came home to it like a bee to a favourite flower, all the way from India... but now, after three weeks, we didn't talk about Bengal or Burma any more. No more talk of wars for us it was agreed. By the three of us. Mash â Marshall Trevor Edmunds â was our third man.

âMind you, all this peace,' Emlyn said, âgives you a right pain in the arse. Unless I've got piles of course. Anyway, what happened to you, after. Last night?'

âMorwenna Williams,' I said.

âJesus H Christ! Nothing doing there, was there?'

âShe said I was drunk...'

âYou'd have to be. You should have stayed with us. Mash and me â we took over the band in that place.' He sniffed. âMorwenna Williams â you must have been really desperate for it, mate.'

The town during the war had been lively with soldiers, a wide open place with girls chancing their luck. That's what I'd heard. But now uniforms gone, sobriety and settle down was the thing. All that warmth had cooled, all that giving had stopped.

âThank God for Lilian,' I said. Lilian Ridetski, the ex-serviceman's standby, who didn't want to get married, who only knew one word and that was welcome; whom we shared, Emlyn Morton and me.

âAmen to that,' he said, then got to his feet. âThere's Mash now.' A giant in a lounge suit waving wildly from the mud bank before he ran, fully clothed, into that dirty, rubbish-strewn river and came swimming out to us, arms flailing, a wash behind him. We gave him a hand up over the side and he nearly had us over. He towered, dripping above us. A good suit that had been, a shirt that had been laundered white and stiff beneath it. There were green tendrils of seaweed on his County School tie.

âGuess where I've been?' he asked, a huge smile on his face.

âFor a swim?' Emlyn suggested.

âNo â to church,' Mash protested. âBeen with father to church!'

He stripped off and hung his clothes on the

Ariadne

's rigging, and he lay down on the deck, a towel around his waist, and went to sleep. He had two scratches on one cheek, and a bruise under his left eye.

âAfter you'd gone,' Emlyn explained. âTwo punch-ups. Who with and what for, I haven't a clue.'

Mash had sat with us on the back row at school, and tried to keep up. Emlyn and I had scholarships, but Mash paid fees otherwise he wouldn't have been there at all. Then they pulled him out and found him a job as a solicitors' clerk â at the biggest solicitors in the country â but licking stamps and running errands was as far as he got. The army sent him to North Africa, later to Europe. In Germany he had been shot in the head by a British paratrooper who was drunk at the time, or it could have been in Holland by a German sniper or somewhere and someone else. Mash forgot. All the time and about everything. He had been waiting for me on the platform of Maelgwyn station when the train brought me home and Emlyn had to tell him who I was. He had all but crushed my hand with his grip.

âWill he mend, d'you think?'

âSo long as they don't send him to any more bloody head doctors he'll be all right,' Emlyn replied.

âThen why do they keep on pushing him? He's always been thick â and they had him going in for exams and all that extra private tuition. And remember that business about making him a great athlete when it was plain to anybody that he might look the part but he'd got two left feet and no co-ordination.'

âWhat do you expect with MT Edmunds for a dad?' He drew his knees up under his chin. âWe were a spell in Kent when we got back. I heard he was in this hospital near Bromley. Went over to see him. He could remember better then and it was a para who shot him. They got into an argument. This para pulls a gun and pops him in the head. Part of his brain went dead â and old MT Edmunds starts writing to the War Office for him to be mentioned in despatches!'

âThey just want to let him be,' I said.

âNo chance. Remember when he got Moses and osmosis mixed up â those Christmas exams in form three? Every bloody question and he wrote “osmosis” for an answer!' He laughed rocking himself gently as he did so.

The air was suddenly filled with the cries of children â a dozen or more of them charging up and down the dunes, shooting the daylight out of each other. âThe trouble with the war,' Emlyn said, âthere weren't any kids about â but this is all right isn't it? We'll get old

Ariadne

fit for the sea, and we'll nudge her south, port by port to the Med, and we'll find us a nice little harbour with white-washed houses behind on a hill and we'll take out tourists and do a bit of fishing. All right?'

âAll right by me,' I said. Mash snored gently, his mouth wide open. âSo long as we don't have to work.'

Then we fell to discussing the local women and the danger of getting caught. And that led us to Lilian Ridetski and visits late at night, and the beauty of the arrangement, without a string attached.

âWhat happens if you're there when I call?' I asked him.

âI'll get off and let you in,' he replied, and went below to the cabin to practise his trumpet. He was good too. In his element in some smoky, dim-lit dance hall, giving the band a lift â but he usually complained afterwards about his lungs or his kidneys.

I lay back and thought of Lilian. Emlyn's discovery. She kept Maison Collette, Ladies High Class Hair Salon, in a little cul-de-sac off the High Street, and she lived alone above the shop. Ring at the door and a light comes on at the back of the shop. The door opens. Smell of scent and shampoo. âPhilip,' she says. âWell, come in.' And the familiar ripple of a laugh to follow. âWhat a surprise. Lovely.' She holds the door open, only wide enough for me to enter and I squeeze myself in and I have to brush against her and she catches hold, her mouth against mine, running her hand over the front of my trousers as she gently eases the door shut. No messing with Lilian. But she had trouble with names now and then.