Say You’re One Of Them (40 page)

—The Most Reverend Camillus Etokudoh,

Bishop of Ikot Ekpene

This book came together because of the presence of many people in my life.

In the name of the Jumbo Akpan-Ituno and Titus Ekanem extended families, I thank you, my brothers and sisters-in-law—Emem and Joy, Aniekan and Nkoyo, and Mfon and Ekaete—and your children; and you, John Uko and Bishop Camillus Etokudoh. You always said it was possible.

I’m also indebted to you, my friends—among whom are Jesuits—who never tired hearing of my big dreams or reading my drafts: Jude Odiaka, Ubong Attai, Mary Ifezime, Edie Nguyen, Itoro Etokakpan, Ndi Nukuna, Isidore Bonabom, Comfort Udoudo-Ukpong, Emma Ugwejeh, Ehi Omoragbon, Lynette Lashley, Emma Orobator, Caitlin Ukpong, Chuks Afiawari, David Toolan, Bob Hamm, Iniobong Ukpoudom, Vic EttaMessi, James Fitzgerald, Peter Chidolue, Bob Reiser, Larry Searles, Abam Mambo, Bill Scanlon, Rose Ngacha, Gabriel Udolisa, Tyolumun Upaa, Barbara Magoha, Christine Escobar, Wes Harris, Matilda Alisigwe, John Stacer, Aitua Iriogbe, Peter Byrne, Amayo Bassey, Funto Okuboyejo, Gozzy Ukairo, Peter Ho Davies, Nick Delbanco, Laura Kasischke, Nancy Reisman, Dennis Glasgow, Fabian Udoh, Greg Carlson, Mark Obu, Prema Bennett, Bob Egan, Arac de Nyeko, John Ofei, Gina Zoot, James Martin, Madonna Braun, Ray Salomone, Jim Stehr, Wale Solaja, Sam Okwuidegbe, Tom Smith, Mike Flecky, Kpanie Addie, Shade Adebayo, Gabriel Massi, Nick Iduwe, Peter Otieno, Dan Mai, Greg Zacharias, Anne Njuguna, Edie Murphy, Alex Irochukwu, Fidelis Divine, Jan Burgess, Jackie Johnson, Chika Eze, Marian Krzyzowski, Eugene Niyonzima, Jeanne Levi-Hinte, Marissa Perry, Celeste Ng, Preeta Samarasan, Peter Mayshle, Anne Stameshkin, Jenni Ferrari-Adler, Phoebe Nobles, Joe Kilduff, Ariel Djanikian, Jasper Caarls, Taemi Lim, Maaza Mengiste, Marjorie Horton, Taiyaba Husain, Rosie and Jerry Matzucek, Ufuoma and Rich Okorigba, Emily and Paul Utulu, Eunice and Dele Ogunmekan, Olive and Thomas Beka, Monica and Cletus Imahe, Mary Ellen and Leslie Glynn, Justina and Raphael Eshiet, the Okuboyejo family, Daniel Herwitz and Mary Price of the University of Michigan’s Institute for the Humanities, and the Akwa Ibom priests and religious in Michigan.

I also wish to thank Cressida Leyshon at

The New Yorker;

Pat Strachan, Marie Salter, and Heather Fain, editor, copyeditor, and publicist, respectively, at Little, Brown and Company; Elise Dillsworth at Little, Brown Book Group; and Eileen Pollack, Gerry McIntyre, and Ekaete Ekop, friends and editors at large. Maria Massie, my agent, you are the best out there.

Last, may the Lord bless you, the people of St. Patrick’s Church, Ikot Akpan Eda; St. Paul’s Parish, Ekparakwa; and the Catholic Diocese of Ikot Ekpene, for your love and generosity to me and my family since my childhood. Through your inspiration, I have stories to tell.

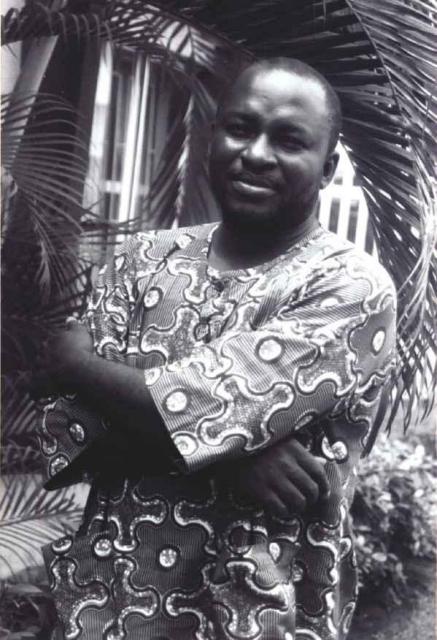

About the Author

I was born under a palm-wine tree in Ikot Akpan Eda in Ikot Ekpene Diocese in Nigeria. I was inspired to write by the people who sit around my village church to share palm wine after Sunday Mass, by the Bible, and by the humor and endurance of the poor. My grandfather was one of those who brought the Catholic Church to our village. I was ordained as a Jesuit priest in 2003, and I like to celebrate the sacraments for my fellow villagers. Some of them have no problem stopping me in the road and asking for confession!

I have very fond memories of my childhood in my village, where everybody knows everybody, and all my paternal uncles still live together in one big compound. When I was growing up, my mother told me folktales and got me and my three brothers to read a lot. I became a fiction writer during my seminary days. I wrote at night, when the community computers were free. Computer viruses ate much of my work. Finally, my friend Wes Harris believed in me enough to get me a laptop. This saved me from the despair of losing my stories and made me begin to see God again in the seminary. The stories on that first laptop are the core of

Say You’re One of Them

. I received my

MFA

in creative writing from the University of Michigan in 2006.

I always look forward to visiting my village. No matter how high the bird flies, its legs still face the earth. When I get back to Ikot Akpan Eda, my people and I will celebrate this book in our own way—with lots of tall tales, spontaneous prayers, and palm wine!

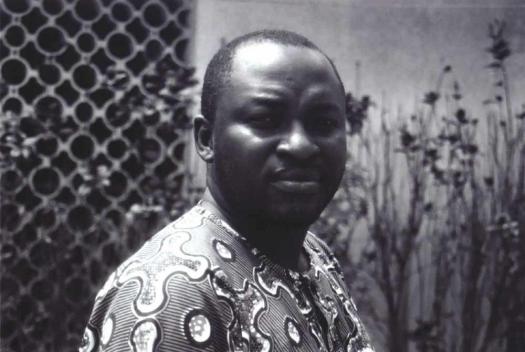

Photograph by Mfon Akpan

Photograph by Mfon Akpan

Say You’re One of Them

Uwem Akpan talks with Cressida Leyshon of

The New Yorker

Your story “An Ex-mas Feast” is about a family living on the street in Nairobi, Kenya. When did you first start thinking about these characters and the world that they inhabit?

When I went to study theology in Nairobi, in 2000, I was taken by the phenomenon of street kids. I’d never seen anything like it before…. I started talking with the bunch of kids around Adams Arcade, which was near my school. These kids were not very wild, because they still went back to their homes in the slums in the evening. There was one kid, Richard, who was their leader. I started calling him Dick. He had some English, and was very respected by the others. If I wanted to give them money, the whole bunch would ask me to give it to Dick, because they knew he would not cheat them. He would talk with me and ask me about Nigeria. I don’t know how he managed to be so nice, unlike his friends. After the Christmas holiday of 2000, he disappeared. I started asking questions. Some of his friends told me that maybe he had gone to the city to become a real street kid. I really thought I would run into him someday in the city. But I never did. I kept hoping that he would keep his gentleness even in the very wild gangs of the City Centre.

You’re working on a collection of stories about children in various countries in Africa. Can you talk a little about the other stories? Why do you want to write about a number of African countries rather than one or two—for example, Nigeria, where you grew up, or Kenya, where you studied for three years?

I would like to see a book about how children are faring in these endless conflicts in Africa. The world is not looking. I think fiction allows us to sit for a while with people we would rather not meet. I have had the chance to study and to travel a bit. I really hope I can visit these places and do good research, so that the stories can be truly those of the people I am trying to write about. I want their voices heard, their faces seen.

Do you find it easy to move between the two continents, Africa and America, or does it take time to adjust to life in each place again?

The rhythm of life here is different from that of Nigeria. I really liked the efficiency and accessibility of things here, the educational opportunities. And I was touched by the beauty and tolerance it has taken to fashion America. But, for instance, the thing about old people staying in “homes” away from home blew my mind. As did how little Americans know or want to know about life elsewhere.

It is a great thing to be able to move back and forth. I get to see my friends. There’s also the challenge of remaining faithful to my roots. Now each time I return to Ikot Akpan Eda, my home, I ask my parents and old people a lot of questions. I am more interested in my Annang culture now than I was before I started coming here. I am always interested in listening to old people in my village. Everybody knows everybody, and people tell tall stories. After Mass on Sunday, people sit together outside the church and share fresh palm wine. One of my mother’s cousins used to come around to our home to tell us stories he made up about different people in the village. He seemed to have a license to change any story into what ever he wanted. My granddad, who helped bring Catholicism to my village, became a polygamist at one point and later came back to monogamy. So I have many uncles and aunties. My father and all his brothers live in one big compound. My mother’s place is not far off.

Have you set much of your fiction in the United States?

I have not set any of my fiction in the U.S…. Not yet. I feel that you guys have tons of writers “discovering” the American experience for you. I feel that the situation of Africa is very urgent and we need more people to help us see the complexity of our lives. Ben Okri has said that rich African literature means rich world literature. Having said that, it would be great to set some of my fiction in this country. A lot of African refugees are coming to America now. So that could be where to begin.

What do you read, mostly?

The stories I find in the Bible keep surprising me. All the crimes are already committed in Genesis, yet God stays with the ones who committed them. I read extensively, though ever since I started writing my reading speed has gone down considerably.

Is your faith important to you when you’re writing? What role, if any, do you think it should play in your fiction?

Since it is not something I can put away, my faith is important to me. I hope I am able to reveal the compassion of God in the faces of the people I write about. I think fiction has a way of doing this without being doctrinaire about it.

In “An Ex-mas Feast,” two of the main characters, Jigana and his sister Maisha, live in a harsh world. Do you think that they’ll survive?

My continent is in distress and has been since the beginning of slavery. Leadership is a big problem. My hope is that things will change in Africa. Eu rope fought endlessly with itself in past centuries; now they have a Europe an Union, not just in name, like the African Union. I hope that someday all the stupid wars on the African continent will end. I am amazed at the endurance of people, whether in Asia or Latin America or Africa, caught up in harsh situations.

What do you do when you want to forget about everything?

[Laughs.] A priest has no way of forgetting about everything! I like to watch good soccer on TV. Take long, slow drives. Read. Visit with people.

Cressida Leyshon’s interview with Uwem Akpan originally appeared at www.newyorker.com. Copyright © Condé Nast Publications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

- Each of the stories in

Say You’re One of Them

is told from the perspective of a child. Do you think this affected your reaction? If the narrators had been adults, might you have felt differently about the stories? Why do you think Akpan chose to depict these events through children’s eyes? How do Akpan’s young characters maintain innocence in the face of corruption and pain?

- In “An Ex-mas Feast,” Maisha leaves her family to become a full- time prostitute. Do you think she chose to depart, or did her family’s poverty force her to flee? Is it possible to have complete freedom of will in such a situation? Is it reasonable to judge a person for her actions if her choice is not entirely her own?

- In “Fattening for Gabon” the children’s uncle and caretaker, Fofo Kpee, sells them into slavery. How does Fofo’s poverty and vanity contribute to his unthinkable actions? Do his pangs of conscience redeem him for you? Why or why not?

- In “What Language is That?” Hadiya and Selam are kept apart by their parents after the escalation of religious conflict. Have you ever experienced a situation in which friends and family have objected to someone in your life for reasons you didn’t understand? What did you do? How did you feel?

- The bus in “Luxurious Hearses” is a microcosm not only of African hierarchies and religions but also of the continent’s numerous languages and dialects. Discuss how speech is related to class, culture, religion, and heritage. How does dialogue function in the other stories? Do we hold similar attitudes about language in our own culture? What are some examples?

- This book takes its title from instructions given to a Rwandan girl by her mother in “My Parents’ Bedroom.” Did the familiar domestic detail in this story—Maman’s perfume, little Jean’s flannel pajamas, toys like Mickey Mouse in the children’s room—intensify for you the horror of what ensued? Is there comparable detail in any of the other stories that helped you to identify with Uwem Akpan’s characters?