Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (20 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

BOOK: Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women

13.34Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

I am a Southern woman, born with revolutionary blood in my veins.

—ROSE O’NEAL GREENHOW

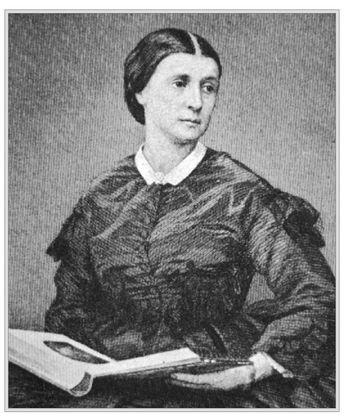

In July 1861 at the height of the Civil War, a young woman managed to deliver vital information about Union troop movements to General Pierre Beauregard of the Confederate army, stationed near a little town called Manassas in Virginia. She kept the small piece of paper, containing a combination of numbers written in ink, hidden in a black silk bag no bigger than a silver dollar tucked in the heavy coil of her dark hair. Where had she gotten the information from? Rose O’Neal Greenhow, a Washington matron, Southern sympathizer, and Confederate spy. When Rose heard of the subsequent Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, she always believed that it was her information that made the difference.

Born Rose O’Neale, her family lived on a small plantation in Montgomery County,

14

Maryland. The middle child of five daughters, she was high-spirited, with dark eyes and a will of iron. When Rose was four years old, her father was found dead by the side of the road, after spending the afternoon and night drinking in a tavern. His favorite slave, Jacob, was tried and convicted for killing his master in a drunken rage. Rose’s mother was given four hundred dollars’ compensation for losing her slave to the gallows.

14

Maryland. The middle child of five daughters, she was high-spirited, with dark eyes and a will of iron. When Rose was four years old, her father was found dead by the side of the road, after spending the afternoon and night drinking in a tavern. His favorite slave, Jacob, was tried and convicted for killing his master in a drunken rage. Rose’s mother was given four hundred dollars’ compensation for losing her slave to the gallows.

Her mother tried to keep the family together and to save the farm, but after a few years, everything was auctioned off to pay the remaining debts. Rose and her sister Ellen were sent to live with an aunt and uncle who ran a boardinghouse in Washington, DC, that served as a temporary home to lawmakers while Congress was in session. The young women were introduced into Washington society through the connections they made while living at the boardinghouse. Rose’s wit was sharp, her manner dynamic, and the politicians were soon calling her “Wild Rose.”

Their days were filled making social calls or spending time in the visitors’ gallery watching the debates on the Senate floor, which was a popular pastime. These were the days when great orators such as Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun took the floor. Women swooned over their favorite orators. Rose became particularly fond of Calhoun, who became a father figure to her, and she often sought his advice. He and Rose became very close; her thoughts about slavery and the South were formed by the time she spent with him. She once wrote about him, “My first crude ideas on State and Federal matters received consistency and shape from the best and wisest man of this century.” Rose’s sisters made socially advantageous marriages, which helped bring her more into society. The next step for Rose was to also make a good marriage.

Robert Greenhow was one of the most eligible bachelors in the capital. From a fine Virginia family, Greenhow was cultured; he’d lived abroad, spoke several languages, and was working for the State Department as a translator and librarian. They were married in 1835. Rose was gregarious and social, while Robert was more comfortable with his books and maps, but they shared an interest in learning. Rose was passionate about preserving the Southern way of life, including slavery. She adamantly opposed the abolitionist movement, believing that blacks were inferior to whites. And she wasn’t hesitant to express her views.

Since Robert was not terribly ambitious, Rose was ambitious enough for the both of them. They socialized two or three times a week, and Rose learned to throw glittering dinner parties. Modeling herself after her idol, Dolley Madison, Rose became an effective and knowledgeable hostess. By the 1840s, Rose was an ardent proslavery expansionist. Over the next two decades she came to know all the movers and shakers in Washington society.

Widowed in 1854, while they were living in California, Rose received a small settlement in regard to her husband’s accidental death, but the money quickly ran out. Moving back to Washington, DC, Rose had to improvise, moving to smaller and smaller residences. The charming widow wore black clothing that she made herself, which emphasized her dramatic coloring. Easing herself back into the social whirl, she soon had several beaux who were quite smitten with her but Rose wasn’t interested in remarrying. She persuaded her old friend James Buchanan to run for president, working tirelessly for his campaign.

When Buchanan was elected, Rose once again was close to the seat of power. She was described by the

New York Herald

as a “bright shining light” in the social life of the new administration. Rose threw popular dinner parties, entertaining both Northerners and Southerners, but tensions ran high in the capital. At a dinner party, Charles Francis Adams’s wife expressed sympathy for the radical abolitionist John Brown. Rose snapped, “I have no sympathy for John Brown. He was a traitor and met a traitor’s doom.” These were strong words from a woman who prided herself on being the epitome of a gracious hostess. When Lincoln was elected president, the world that Rose knew came to an end.

New York Herald

as a “bright shining light” in the social life of the new administration. Rose threw popular dinner parties, entertaining both Northerners and Southerners, but tensions ran high in the capital. At a dinner party, Charles Francis Adams’s wife expressed sympathy for the radical abolitionist John Brown. Rose snapped, “I have no sympathy for John Brown. He was a traitor and met a traitor’s doom.” These were strong words from a woman who prided herself on being the epitome of a gracious hostess. When Lincoln was elected president, the world that Rose knew came to an end.

With the Southern states seceding from the Union, Rose was eager to help any way that she could. She was recruited by Captain Thomas Jordan of the Confederacy, who taught her basic cryptography, which she diligently practiced. Although she was no longer in the inner circle, Rose still had connections in Washington, which she used to get information to send to the Confederate army stationed in Virginia under Beauregard. Using her feminine wiles, she cajoled military secrets from Union sympathizers who were so blinded by her charms, they loosened their tongues without even realizing what they were doing. Rose didn’t limit herself to powerful men but also their clerks and aides as well.

Rose, not being a trained spy, was a little careless. She kept copies of information that she had sent and didn’t completely destroy information that she had received. Her neighbors became suspicious of her and one of them reported her to Thomas Scott, who was the new assistant secretary of war. Thomas Scott hired Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and put him on the case. Pinkerton was in Washington under an assumed name, Major E. J. Allen, working on counterintelligence as part of the fledgling U.S. Secret Service. He had set up a network of informants in the South who were sympathetic to ending the Civil War.

In August 1861, Rose was arrested on the doorstep outside her house just as she popped a note in her mouth and swallowed. The detectives put her and her youngest daughter, little Rose, under house arrest after they ransacked the house searching for evidence. Although they found a large number of documents and maps, including the ones that Rose had sewn into her dress, they missed others that she was able to destroy. A prisoner in her own home, she was watched constantly, even at night; she had to sleep with her door open. Anyone who tried to visit her was arrested. Soon other prisoners were brought to her house to join her. Rose was outraged that lower-class women “of bad character” were placed in her home.

Rose made things difficult for her guards as well as herself. She complained that her rights were being trampled on, that the food was inedible, that she had no privacy. Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus shortly after the war started. Although she was under arrest, Rose still managed to get information to her string of informants. Some of her messages didn’t go through and were added to the pile of evidence against her. Rose wrote a letter to Secretary of State William H. Seward protesting her imprisonment. “The iron heel or power may keep down, but it cannot crush out, the spirit of resistance, armed for the defense of their rights: and I tell you now, sir, that you are standing over a crater, whose smothered fires in a moment may burst forth.” A copy found its way to the

Richmond Whig

. The newspaper called it the “most graphic sketch yet given to the world of the cruel and dastardly tyranny” of the Yankee government. Rose’s imprisonment made her a martyr in the eyes of the South. The evil Yankees who could imprison a mother and child were grist for the propaganda mill.

Richmond Whig

. The newspaper called it the “most graphic sketch yet given to the world of the cruel and dastardly tyranny” of the Yankee government. Rose’s imprisonment made her a martyr in the eyes of the South. The evil Yankees who could imprison a mother and child were grist for the propaganda mill.

After several months under house arrest, Rose and her daughter were moved to her former childhood home, her aunt’s boardinghouse, which had been turned into a Union prison. The room they were confined in would have been familiar to Rose; it was the same one where she had nursed her dying hero, Senator Calhoun in 1850, treasuring his last words. Rose complained about having to share the prison with Negro prisoners. The room was filled with vermin, so Rose would use a lit candle to burn them off the wall. She tucked clothes underneath the mattress to make it more comfortable for her little daughter. Somehow she even managed to smuggle in a pistol even though she had no ammunition.

After almost eight months in prison, Rose was finally brought up on charges of espionage. Rose was feisty and defiant to the members of the commission. Without counsel, she demanded to know what evidence they had against her, and she complained that her rights were being trampled. When they presented their evidence, including a letter Rose wrote that gave details of the Union army’s movements, Rose brazened it out, giving them no satisfaction. Although her actions were treasonable, Lincoln was reluctant to have her stand trial. Treason was a hanging offense but Lincoln had no stomach for hanging a woman. Something had to be done, though; Rose was considered too dangerous. She was given a choice: either swear allegiance to the Union or be deported to the Confederacy. Rose agreed to be deported to the South.

On May 31, 1862, after almost ten months in prison, four months on house arrest, and five months in the Capitol prison, Rose was escorted out of the city that had been her home for more than thirty years. Did she feel a pang as the wagon passed through the streets of the city where she had met her husband, given birth to her children and buried them, the avenues where she had strolled with her beaux and her sisters? Rose would never see the city again.

Before Rose was allowed to set foot on Confederate soil, she had to sign a statement as a condition of her parole that she would never set foot in the North again while the war continued. In Richmond, Rose was welcomed with open arms. She was hailed as a heroine, a true daughter of Dixie who defied the North. At a welcoming lunch, Rose cheekily raised her glass and toasted the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. Davis granted her twenty-five hundred dollars for her services to the Confederacy. After her arrival, Rose was sent by Davis to Europe to drum up support for the South’s cause. Despite the fact that she suffered greatly from seasickness, Rose was eager to go.

She went to France to plead with Emperor Napoleon III and to England to do the same with Queen Victoria. Although privately people were sympathetic, Rose could not get anyone in Parliament or Napoleon III to publicly come out in support of the South or to recognize the Confederate states. In her first two months abroad, she wrote her memoir,

My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington

, which sold well in Britain. She dedicated the work to “the brave soldiers who have fought and bled in this glorious struggle for freedom.” The book is a valuable record of Southern sentiment that led up to the Civil War.

My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington

, which sold well in Britain. She dedicated the work to “the brave soldiers who have fought and bled in this glorious struggle for freedom.” The book is a valuable record of Southern sentiment that led up to the Civil War.

Rose drowned off the coast of North Carolina on October 1, 1864, when the ship in which she was returning to America ran aground at the mouth of Cape Fear, chased by a Union gunboat. Although the captain advised that everyone stay on board, Rose was frightened of being captured by the Yankees again. She was on her way to shore when her rowboat was overturned by a large wave. Her body was found washed up onshore a few days later. She had been weighed down by gold sewn into her clothing. Searchers also found a copy of her book,

Imprisonment

, hidden on her person.

Imprisonment

, hidden on her person.

She was given a full military burial, wrapped in the Confederate flag, in Oakdale Cemetery, near Wilmington, North Carolina. The

Wilmington Sentinel

wrote that her funeral “was a solemn and imposing spectacle . . . the tide of visitors, women and children with streaming eyes, and soldiers with bent heads and hushed stares standing by, paying the last tribute of respect to their departed heroine.” Her grave bears the inscription “Mrs. Rose O’N. Greenhow. A Bearer of Dispatches to the Confederate Government.” Every year on the anniversary of her death, a ceremony is held to honor her contributions to the Confederate cause.

Wilmington Sentinel

wrote that her funeral “was a solemn and imposing spectacle . . . the tide of visitors, women and children with streaming eyes, and soldiers with bent heads and hushed stares standing by, paying the last tribute of respect to their departed heroine.” Her grave bears the inscription “Mrs. Rose O’N. Greenhow. A Bearer of Dispatches to the Confederate Government.” Every year on the anniversary of her death, a ceremony is held to honor her contributions to the Confederate cause.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was not to be admired for her views about slavery. But her devotion to the Confederacy and her ability to further her cause through her charm and determination certainly made her one of the most dangerous and formidable women in the country. Although her spying career was brief, and there is doubt among historians about the value of the information she was able to pass on, Rose proved that even through traditional means, women could be effective instruments of war.

Other books

Geek Chic by Margie Palatini

At Last Comes Love by Mary Balogh

This Is for the Mara Salvatrucha by Samuel Logan

Soul Guard (Elemental Book 5) by Rain Oxford

October Skies by Alex Scarrow

The Mail Order Bride's Quilt by Atwood, Leah

Jesse's Starship 3: Joshua's Walls by Saxon Andrew

Deep Desire: The Deep Series, Book 1 by Z.A. Maxfield

The Straight Crimes by Matt Juhl

Chthon by Piers Anthony