Scared Yet? (8 page)

While she listened to him grumble, a spotlight lit up on the other side of the fence. The courtyard filled with a dim glow broken up by long, dark shadows. A dog barked, a quick yap-yap. Liv pulled the sheet back further and peered out.

âHave you got any homework tonight?' she asked, trying to change Cameron's focus. As he told her about a seven-times-table test, someone walked through the arc of light on the other side of the fence and a long, eerie shadow moved across Liv's yard. She stepped back from the glass, watched cautiously. âSo what's seven times six?'

In the silence while he thought, she tried the handle on the door. It was locked but loose. Like the front door.

âForty-two.'

âWell done. Seven times eight?' She pushed the door hard into the frame, flipped the latch up and down and tried it again. Still loose.

âFifty-four.'

âAre you sure?'

âMmm . . .'

Liv gave the door a firm, quick yank. It pulled off the latch and popped open. She gasped as a gust of cool night air blew over her face.

âWhat?' Cameron said.

She slammed the door, flicked the latch down to the lock position and dropped the curtain over the glass. âNothing. I . . . ah, I think you need to work on your maths some more. Why don't you practise in the bath? It's getting cold

outside, you should go back inside.' She had no idea what Thomas's yard looked like but she didn't want him out there now. In the dark by himself.

âOkay.'

âIf anyone asks, I'm fine. It's just a bruise. I'll show you on Monday.'

âOkay.'

âI'll talk to you tomorrow. I love you, Cam.'

âLove ya, Mum. See ya.'

Liv put the phone on the bench and looked warily at the back windows. The sheet didn't reach the floor. Beneath it, she saw the reflection of her lower legs in the glass. She heard a throaty voice whisper in her head and felt suddenly, dangerously exposed.

10

Liv backed into the room as a churning started up in her gut. Why hadn't she noticed the doors before now? Because the previous owners had lived with them. Because it was a safe neighbourhood.

She thought Jamestown was a safe place to work until last night. And before today, she'd never had a cop tell her to take security precautions. Or a violent man whisper in her ear. Or a sick note left on her car.

She ran her eyes around the room. There was a window over the kitchen sink, she'd have to check that, too. But the doors came first.

She found a broom in the laundry cupboard, took a few minutes loosening the head then dropped the handle into the track for the glass sliding door. When she tried the door again, it opened only a few centimetres. Not wide enough for a child to squeeze through. But it's not a child you're worried about, Liv. The doors were glass and glass could be broken.

At the front door, she twisted the deadbolt back and forth. It worked like it should, as far as she could tell, but there was a gap between the door and the jamb all the way around and it rattled about with a half-hearted thrust. She grabbed the weekend newspaper from the coffee table and wedged it under the entry, gave the timber a push. Okay, that felt solid.

She stood back, looked at her handiwork, thought about a hefty whack with the heel of a boot and wondered how difficult it would be to knock the whole door out of its hinges.

â

The daughter of former national heavyweight boxing champion, Tony “The Wall” Wallace, showed some of her father's fighting spirit when she took on an assailant in a car park last night.

'

Liv hardly recognised her own face on the TV. She hoped Cameron wasn't watching. She'd never seen her dad bruised from a fight. She was a year old when he had his last one â and his opponent never got close enough to mark his face. It was nice Sheridan had called him a former champion. He was usually remembered for the world title fight he passed up.

Liv sat in the corner of a sofa with a dinner of cheese and crackers and watched herself. Without specifying the cancer, Sheridan mentioned her father's illness as though it was an added indignity to Liv's injuries. Rachel Quest was interviewed as well, warning women to be careful, asking for witnesses to call Crime Stoppers. Daniel Beck

didn't make an appearance. The story ended with her own words of experience. âNo, I wasn't scared. I hit back and IÂ screamed. That's what saved me.'

Was that bastard watching the news, too? She hoped he was thinking twice about hiding in car parks. And that the next woman destined to pass him in the dark had listened up.

It was after nine when she finally heard from Kelly. AÂ brief text message:

J told me bout note. You okay? Want

Â

to come over?

The invitation was tempting, especially now that Liv knew the precarious condition of her locks, but the idea of heading out into the night wasn't appealing. Not twenty-four hours after being beaten up in the dark.

No. OK here. Sorry missed meeting. How was it?

2 late to go into it. Tell you 2morrow. Sleep well. X

She wished Kelly had rung so she'd been able to hear the inflection in her voice. Was

2 late to go into it

good or bad news?

Liv flinched awake, batting at the hand reaching for her in the dream. Early-morning glare coming in under the sheet over the bedroom window made her wince in pain. She rolled away from it and sat on the edge of the bed, fatigue like a five-tonne weight draped over her shoulders.

She'd done what she could to put her mind at rest, pushing packing cases against the front door and the garage access door, blocking the entry to her bedroom with a bedside table, but she hadn't been able to switch off the

twitchy hypersensitivity to every sound in the townhouse. The timber creaking in the walls, the late-night whir of the fridge, a shout in the street, the dog next door barking. Not the cute yap-yap he did at dinnertime but a long, continuous racket. Then in snatches of sleep when exhaustion had won, her mind had whirled with images from the car park â the movement in the window, the hand over her mouth, a man lunging, Daniel Beck looming.

She poked gently at the swelling on her face â still huge â noticed Kelly's phone on the floor, the lights out, battery dead. Great. She hadn't installed a landline in the townhouse, figuring she'd take advantage of the financial benefits of her mobile account. But there was no advantage if someone broke in and you couldn't ring for help.

Kelly's last message had given her plenty of reason for lost sleep, too. Liv could recite the figures off by heart, just wished she knew what Neil had made of them.

You're not losing the business, she told herself. Not today. Prescott and Weeks was still on its feet. She stood up, muttered, âStill walking and talking, guys.'

She stripped out of her pyjamas and ran the shower, taking stock of her spreading bruises as the water heated up. Her face was worse, if that was possible. Cam would be impressed with the brewing green one on her hip. And yesterday's row of dots on the insides of her arms looked more like what they were â fingerprints.

Rachel Quest was out when Liv got to the police station. She left the note from her windscreen with the officer at the front desk, and hoped that whatever had kept her on

the side of a busy road yesterday didn't take up all her time and attention today.

She found a spot on Park Street, in a two-hour zone a couple of blocks from the office. The parking cops could be swift and merciless but she figured walking the distance with the crowd on the footpath was safe. She ignored the glances at her injuries, searched for bruises in the faces that passed her, felt wary and a little anxious by the time she reached work.

Daniel straightened up as she shouldered open his office door. He was at the reception counter with a clipboard and an array of boxes stacked in the small space behind the desk. Liv had never seen anyone but him in the office. She guessed he wasn't going to save their client problem.

âLet me give you a hand.' He walked around and held the door open. He seemed preoccupied, not exactly ecstatic to see her.

So she'd make it quick. âAnd let me give you a coffee.' She held out the cardboard tray with two large take-outs on it. âLenny said you like a flat white with two sugars. That's the one on the right.'

His eyes did a quick down to the cups and back up. There was surprise and bewilderment in them and what she hoped was the edginess of a caffeine addict still working on his morning fix, not irritation at being interrupted. âI've got no idea why you're bringing me coffee but I won't say no. Thanks.' He took the whole tray from her, ushered her all the way in.

âAnd by the way, it's not just this coffee. I've paid your bill at Lenny's for the next month as a thankyou for the other night.'

âThat's not necessary.'

âMaybe not but it's done already.' She cocked her head towards his cup, like he should take it and stop carrying on.

He raised it in a toast. âThen thanks.'

âJust help yourself to anything at Lenny's.'

âReally, the coffee is enough.'

âHave you tried his lemon tart?'

âShould I?'

âIf you know what's good for you.'

She returned his toast with the second cup from the tray and took a long draught. She knew all about the morning fix.

âYour face looks a little better today,' he said.

âYeah right.'

One side of his mouth moved with the beginnings of a smile. âHow's your hand?'

She held it out, flexed the fingers a couple of times. The knuckle felt like a balloon under pressure. âIt's going to take a while.'

âI saw you on the news last night. It was gutsy.'

âThanks.'

âAnd I take back what I thought about you punching your attacker in the car park.'

âWhat did you think?'

âSomething I'm guessing doesn't apply to the daughter of a heavyweight boxer.'

She raised an eyebrow. âProbably a good guess. Can IÂ ask you a question?'

He paused. It looked more cautious than curious. âOkay.'

âI'm wondering if you do home security.' She nodded towards the lettering on his door.

Another pause. âIs this about the assault?'

âSort of.' He'd already done enough running to her rescue. He didn't need to know about the note.

âI don't usually do domestic work. I consult on workplace issues. What were you after?'

âI've just moved into a new place and I want the locks updated. Do you know anyone who can do it?'

âHow big a job is it?'

âIt's a two-bedroom townhouse.'

âDo you want an alarm?'

An alarm was exactly what she wanted. âI can't afford a wired-in system. I was thinking of big, solid, unbreakable locks. Front and back doors and all the windows.'

He pulled a mobile from his shirt pocket. âI can give you a couple of names.'

âHow quickly would they do it?'

âHow quickly do you want it?'

âToday.'

He kept his eyes on her face for a long moment, maybe deciding how serious she was about the time frame, then glanced at the stacked boxes. âI'm seeing my supplier today. I can get you the locks at a good price and I know someone who might be able to install at short notice. He owes me a favour. Let me make a call and get back to you.'

*

âWho's sending you flowers, Tee?' Liv asked when she finally walked into Prescott and Weeks.

Teagan peered from behind a spray of orchids, looking just like Kelly at the same age. âThey're for you. Here's the card.'

âMe?' Liv took the slip of paper and read it.

Hope you're feeling better soon. Best wishes from Hanney and Partners.

A client. A very thoughtful client.

âAnd the others.' Teagan pointed past the orchids to a posy in a gift box and hot pink roses wrapped in cellophane. Liv read the attached notes with surprise. âWe haven't got enough clients but the ones we've got are lovely.'

âThat's not all. There's a bunch of cards for you, too. Kelly told me to open them so you wouldn't have to do it with your sore hand. They're on your desk.'

âWho would've thought getting beaten up would make me so popular?' She glanced at Kelly's office. She was on the phone with the door closed but she waved at Liv, pointed at the receiver.

âWho's Kelly talking to?'

âIt's Toby Wright again.'

That was better than flowers or a card. She sent Kelly a thumbs up as she headed for her own office. While she waited for her computer to come to life, she flicked through the pile of mail. Wow, she really was popular. There were cards and notes from some of their temp staff, one from a client she hadn't spoken to since he retired a couple of years ago, one signature she couldn't read â and one unsigned sheet of paper.

Her hand stopped. The unsigned page was halfway through the pile, most of its contents hidden by the mail above it. She slid it from the stack slowly, as though caution might make it something else.

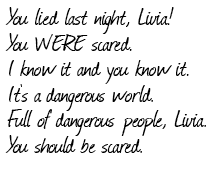

It didn't. It was plain, white, A4 paper. Two crossed crease marks where it'd been folded into quarters. The lines were arranged down the centre like a poem. And the smallish, scrawled handwriting made her heart pound.