Scene of the Crime (26 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

In taking out an arrest warrant following a murder, the officer must be absolutely exact in what s/he says. In the past, courts have

ruled arrests invalid and even overturned convictions because the warrant and the indictment based on the warrant did not state that the subject shot the victim

with a gun

(it could have been with a crossbow); drowned the victim

in water

(it could have been in a butt of Malmsey); or burned the victim

with fire

(it could have been with acid). This means that the findings of the examining pathologist are critical in making a case for murder. Consider these gray areas: If a person dies of a heart attack after the assailant sticks a gun in his face and threatens to shoot him, is that murder? (In most states, probably not.)

English common law, on which the statute law in all of the United States except Louisiana is based (Louisiana's law is based on the French Napoleonic Code), holds that any criminal is guilty of any result that a reasonable person would expect to follow the action the criminal took. That is, if the criminal takes a pistol and holds up a store and the pistol accidentally goes off and kills someone, then the criminal is guilty of murder, because any reasonable person would assume that a person who uses a loaded weapon in the commission of a felony intended murder. However, statute law varies from state to state, so before basing a story on this common law, you must check with your local district attorney, a lawyer, a law library, or the state attorney general's office. In Utah recently, a man who had shot and killed a pregnant woman, in front of her other children, was convicted of a lesser offense than capital murder because he insisted, and was able to convince a jury, that the loaded pistol he was holding to her head while robbing a video store "accidentally" went off.

Death by gun, knife, fire, bludgeoning—these are pretty obvious, and the autopsy is often little more than a legal formality. The serial killer who gets away with it for years not because nobody can find him but because nobody knows murder is happening is usually setting up apparent illnesses (typhoid fever), good accidents ("The Brides in the Bath"), doing careful strangulation ("The Death Angel"), or using poison. (How many do you want me to name?)

The brides in the bath:

George J. Smith just couldn't seem to keep a wife.

He abandoned Beatrice Thornhill, his first wife and the only legal one. She didn't know until much later how lucky she was.

He was using the name Henry Williams when he "married"

Bessie Mundy. Poor Bessie died in her bathtub at Heme Bay, leaving a small fortune to her spouse.

The grieving widower next married Alice Burnham, who was possessed of small fortune. Ever provident, George saw to it she got life insurance. Poor Alice died in her bathtub in Blackpool. Her spouse, of course, collected.

His next wife, Margaret Elizabeth Lofty, also well insured, died in her bathtub in Highgate. This time more newspapers picked up the story, and when Mr. Burnham, Smith's previous father-in-law, heard the story, he was curious—very, very curious.

The police soon shared his curiosity.

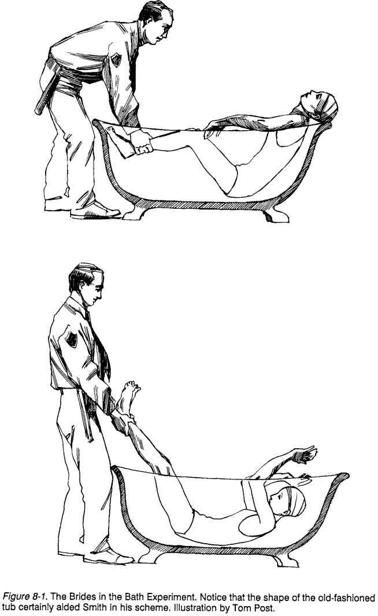

Brilliant forensic pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury thought perhaps the murderer had "simultaneously lift[ed] the knees and press[ed] on the head, so that the body slid along the bath, taking the head under water" (Gaute and Odell 214). Because there was no sign of struggle whatever, and no marks except a slight bruise on the heel of one victim, police were not fully satisfied with that theory but were unable to come up with a better one. They decided to try an experiment. They enlisted the aid of a young woman who was an expert swimmer. Clad in a swimsuit, she sat down in a full bathtub, and a policeman standing at the end of the tub nearest her feet seized her by the heel and yanked. Instantly her feet flew up and the rest of her body slid down into the water. The woman, though alert, healthy and expecting the attack, nearly drowned. After she was revived, half an hour later, she said water was forced into her mouth and lungs so quickly she hadn't time to do anything, even hold her breath. (In early experiments, when police tried following Spilsbury's suggestion, she had plenty of time to resist.)

See Figure 8-1, which shows the sequence of the experiment.

The death angel:

Poor Jeanne was so sweet. Even after her own children died one right after the other, she was still so happy to look after her nieces and nephews, and the children of her neighbors. In fact, she would beg for the opportunity; being around children made her feel closer to her dead darlings. When the babies died, as the poor things so often did, nobody was louder in grief at the funeral, in sympathy for the mother, than Jeanne. Nobody thought a thing—

Until a neighbor arrived home unexpectedly early and entered her baby's room, to catch Jeanne in the act of strangling the child.

Incredibly, Jeanne Weber was repeatedly caught in the act be-

fore doctors or police would pay any attention; police tended to ignore complaints from slums, and doctors kept insisting the babies had died of fits or convulsions or cramps. Even more incredibly, her neighbors and relatives allowed her to go on babysitting. She was tried once and acquitted; after that, she was hired to work in a children's home by a philanthropist who wanted to show how sorry society was about her being falsely accused! The children's home discharged her after several children were severely injured, but did not report her.

It was only after she had killed two more children that she was rearrested, this time winding up in a mental hospital rather than a prison. Two years later, she did the theoretically impossible: She succeeded in strangling herself to death.

Even after she died in 1910, some of the officials who had continued to insist on her innocence swore she had committed only one murder, the last one, in which the tiny victim was severely mutilated as well as manually strangled. Their explanation? She had been so often accused of murder that eventually her mind snapped and she did what she had been accused of!

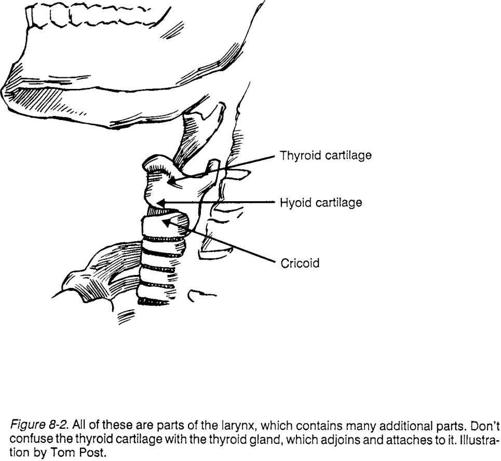

Nobody was ever able to determine for sure whether Jeanne had killed her own children, though the evidence was strong, because decomposition had proceeded to the extent that the hyoid, cricoid and thyroid were no longer discernible.

Why did she do it? Nobody ever knew. Jeanne loved babies. She'd tell anybody so. And she played with them so nicely—as long as she was carefully watched every second.

Hidden Serial Killers

Why does this type of murder so often succeed? Why, even today, do we occasionally hear of investigation into a slightly suspicious death that leads to the discovery of a five, ten, twenty-year trail of corpses? It's not, generally, because medical science can't find the answer. It's because nobody ever suspected anything, and so no autopsy was ever performed.

Of course there are still tricky ones —like Carl Coppolino, whose wife died suddenly of a heart attack. He might have gotten away with it, if his rejected mistress (whose husband had also died of a convenient heart attack probably induced by the muscle relaxant Coppolino had provided her to inject into her husband) hadn't gone to the police after Carl married someone else only three weeks after his wife's death. When the rejected mistress tattled, Carmela Cop-polino was exhumed. Not only was there evidence of some sort of injection—probably of the same muscle relaxant that had been used on the mistress's husband—but also of strangulation (her cricoid was crushed).

Figure 8-2 illustrates the relative location of the thyroid, the cricoid and the hyoid, which were also discussed in chapter seven.

Other cases of murder by injection include the killing on May 3, 1957, of Elizabeth Barlow, whose husband, Kenneth, under the guise of injecting an abortifacient to get rid of the six-week pregnancy she didn't want, instead repeatedly injected her with insulin until she died of induced acute hypoglycemia.

Proving Disguised Murder

This sort of thing tends to be extremely difficult to prove; indeed, any case involving exhumation is difficult to prove. There are several problems.

• First, after a body has been buried, it takes probable cause, not mere suspicion, to obtain a court order for exhumation. The family is likely to fight the order on the basis that their loved one's grave is being desecrated; if—as is most often the case— the suspect is a member of the family, it is difficult to distinguish between that sort of protest and the protest of the murderer.

• Second, embalming removes many of the evidences of crime. Remember that in embalming, as much as possible of the blood is drained from the body and replaced by embalming fluid.

• Third, the condition of the body despite embalming and a sealed coffin may not be good. In any climate but a constantly dry or freezing cold one, but especially in a hot, wet climate, the best embalming can do is delay decomposition for a short time. (That's one reason I strongly suspect that the body of Lenin on display in Russia is largely wax.) I once needed, for a novel, to know whether the body of a six-week-pregnant woman in Galveston, Texas, buried for three years, could be exhumed and the fetus's blood type determined. Pathologists in Galveston County assured me that not only could the fetus's

blood type not be determined, it would almost certainly be impossible to determine even that the woman had been pregnant at the time of death. Scratch one intended plot complication.

• Fourth, even with minimal decay, some evidences are hard to locate. Can you imagine looking for a needle puncture in the body of a woman who has been dead for months? It's hard enough to find one in your own arm three hours after a flu shot.

• And finally, soil conditions can have considerable effect on the investigation. For example, in many areas, groundwater contains an appreciable quantity of arsenic. Although this arsenic fosters good preservation of the body, it also may make it impossible to determine whether the arsenic got into the body before or after death.

What if Some Body Parts Are Missing?

Another situation in which the pathologist may find it difficult if not impossible to determine the cause of death is that in which only part of the body has been located. But that, of course, depends on what the cause of death actually was. If the victim was shot in the head and the head was subsequently removed, there may be no obvious cause of death. In that case, assuming that a good suspect and probable cause for arrest are developed, the arrest warrant must state that X murdered Y on or about such-and-such a date in a manner that cannot be determined—the same type of statement that is necessary in a case such as that of L. Ewing Scott, whose victim's body was never found. In such a case, it is more difficult, but certainly not impossible, to get a conviction.

Tools of the Investigative Trade

What are some of the tools available in the forensic pathology laboratory? An uncopyrighted article by James Geer of the FBI's laboratory division mentions forensic serology, electrophoresis, liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, ion chromatography, mass spectrometry, "optical and instrumental methods of collecting, handling, preparing, identifying, and comparing hair, textile fibers, and other types of fibrous materials," atomic absorption analysis, "genetics, protein and enzyme chemistry, protein polymorphism... and isoelectric focusing and [its] application to bloodstain analysis" (91). Most large-town pathology laboratories have at least serology, liquid and gas chromatography, and mass spectrometry equipment handy; for things they do not possess, they may turn to the closest big-city laboratories, to state laboratories, or to the FBI laboratory. To find out what your town has available, talk with the coroner and/or medical examiner.