Scent and Subversion (19 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

by Alyssa Ashley for Houbigant (1969)

In the late 1960s, Alyssa Ashley was introduced to the Houbigant Parquet division of perfumes. According to a website that was up until recently, it was the hippie era that influenced perfume’s nostalgic look back to the animal notes of civet, musk, and ambergris, which were actually the names of the Alyssa Ashley perfumes themselves, and part of their “Natural Primitives” collection:

At the end of the ’60s … music changed, habits changed, fashion changed. The young generation, starting from the USA and England, embraced oriental philosophies looking for a simpler, more natural lifestyle. This new style of living also reflected itself in perfume. Young people no longer wanted the sophisticated fragrances worn by their parents, but embraced the simple ones whose roots lay in oriental culture. The hippies and the flower children bought the fashionable essential oils, and in 1969 Alyssa Ashley launched their first product, Musk Oil.

My first introduction to Alyssa Ashley’s musk was via a modern formulation. (Of all the Natural Primitives, Musk is the only one still available, albeit in a reformulated version.) I wasn’t that taken with it, but decided to give the vintage a try. I won an eBay auction of a vintage Musk “roll-on” from the 1970s, for 99 cents. More floral and brighter than Civet and less spicy than Ambergris, Alyssa Ashley Musk is a happy, bright, clean musk with a hint of baby powder, the scent of freshly washed hair and skin, but with warmth.

Notes not available.

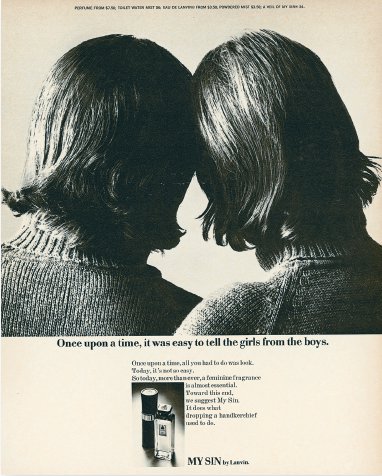

In this amazing 1969 ad from Lanvin for My Sin perfume, a man and woman with identical haircuts and sweaters shown from behind represent anxiety over the ways in which feminism, women’s liberation, and the sexual revolution threaten to erase sexual difference altogether. “Once upon a time,” the ad begins, “it was easy to tell the girls from the boys … all you had to do was look.” Where vision fails, the conventionally gendered perfume steps in.

by Norell (1969)

Perfumer:

Josephine Catapano

Josephine Catapano’s favorite composition, Norell is a beautifully blended green floral that approaches chypre-hood but stops short, like a woman who removes the one accessory—a statement necklace or stiletto heels—that would make her outfit more formal.

It starts off bright and fresh, moves into radiant floral mode, and dries down to a slightly sweet and soapy/woody floral warmth, like suntanned skin plus flowers.

Lots of women, adhering to Coco Chanel’s dictum that a woman should smell like a woman and not a rose, find the floral category matronly, unsexy, or (gasp!) too conventional. I’m beginning to think, however, that floral beauties like Norell and another Josephine Catapano creation, Fidji, are the little black dresses of the perfume world. Sometimes, you just want to smell good without thinking about it too much.

What distinguishes Norell from some of the flower bombs of today is its green opening and its development toward a soft, ambery/woody drydown. It does its dazzling thing for a bit, and exits softly and with grace.

Top notes:

Hyacinth, galbanum, bergamot, narcissus, lemon

Heart notes:

Carnation, jasmine, rose, orris, orchid

Base notes:

Sandalwood, musk, cedarwood, moss, amber

by Lancôme (1969)

Perfumer:

Robert Gonnon

A precursor to Clarins’ Eau Dynamisante, Ô de Lancôme is a light, lemony, fresh chypre with a substantial-enough base to make you wonder why citrus chypres aren’t still made that are rooted to earth. Unlike CK One or other fresh 1990s scents, this has a base that anchors you to a foundation—to earth, moss, trees, vetiver. It smells natural. There’s a gorgeous interplay between the hesperidic top notes and light florals, but it’s the drydown that will captivate your heart. I want to bathe in this stuff. Tart, green, herbal, woody-mossy; one of the best citruses out there. (Word on the street is the reformulation isn’t as nice.)

Top notes:

Bergamot, lemon, tangerine

Heart notes:

Basil, rosemary, coriander, honeysuckle, jasmine

Base notes:

Sandalwood, vetiver, oakmoss, cistus labdanum

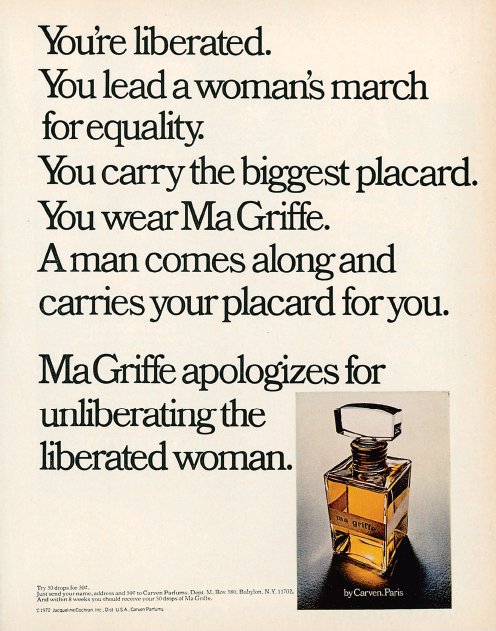

You can almost hear marketers thinking in this 1972 ad for Ma Griffe: “How can something as old-fashioned as perfume be relevant to the newly liberated woman?” Easy! By creating nostalgia for the prefeminist utopia of “unliberation”: a world in which men take care of women.

Aliage, Diorella, White Linen (1970–1979)

Y

ou can really feel in many 1970s scents a kind of loosening up, a freshness, a breeziness that seems implicitly tied to the women’s movement, and perhaps, an escape from the tinderbox that was the 1960s. Many green, fresh masterpieces populate this decade, allowing women to smell austere, powerful, thoughtful, and delicate—sometimes all at once. (Men’s scents get greened, as well.)

I was looking at an early-1970s issue of

Vogue

with a friend, and she remarked that unlike today, the young models looked like women and not teenage girls. Just think of the supermodels then: Gia Carangi, Karen Graham, Beverly Johnson, and Lisa Taylor. They were in their twenties, and their faces looked adult rather than adolescent—knowing, womanly, and even sexually intimidating. Perfumes from the 1970s share that unapologetic sophistication. They weren’t afraid of being a little difficult and complex. After all, teens already had their own scents, like Love’s Baby Soft and Blue Jeans by Shulton. This division that once existed between women and girls seems almost nonexistent now in fashion and pop culture in general.

In addition to being unapologetically adult, 1970s perfumes weren’t afraid to gender-bend or get a little dirty. The chypre category, like the ideal 1970s woman, is on the verge of androgyny, and many florals, chypres, and green scents from the 1970s maintained an allegiance to the body by retaining traces of its musky sweat in the notes. They weren’t trying to mask the body—just embrace it.

For a moment, for lines like Coty’s Sweet Earth, there was a return to the nineteenth-century soliflore, with perfumes constructed around one perfume note—for example, Honeysuckle, Gardenia, or Hyacinth. Alyssa Ashley for Houbigant got into the retro mood as well with the Natural Primitives line of perfumes named after animal base notes: Ambergris, Musk, and Civet.

by Givenchy (1970)

A green/floral chypre, Givenchy III is pretty much perfection. It starts off with a mouthwatering combo of green/citrus notes (galbanum and mandarin) and fruit/flowers (peach and gardenia), which add luscious candied juiciness to the dry, refined, and elegant greenness of this chypre. You almost forget its coquettish brightness as it dries down to a woody, powdery, spicy, and warm ambery base.

The peach and galbanum combo must have inspired Estée Lauder’s Aliage, which came out two years later. Aliage distilled, simplified, and amplified those notes, chopping off the almost-melancholy notes that follow in their wake. (After all, what sport scent gets all brooding and philosophical?)

Givenchy III, in contrast, almost immediately moves from that upper register of sunshine and happiness by drying down into a softer, more-contemplative mood with hyacinth and iris in its base.

There are almost two perfumes on top of each other in Givenchy III, each with different personalities. What’s wonderful is Givenchy III’s ability to reconcile these two moods into one; you can actually still smell those early notes as the perfume’s dusk arrives, like the René Magritte paintings that seem to occur on the cusp between daytime and nighttime.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, bergamot, mandarin, galbanum, peach, gardenia

Heart notes:

Lily of the valley, hyacinth, rose, jasmine, iris root

Base notes:

Patchouli, oakmoss, amber, sandalwood

by Revlon (1970)

A little Moon Drops perfume on my pulse points, a polyester maxi dress, some frosty orange lipstick, and this ’70s lady is ready for the Key Party! From its hippie-dippy name to its sexy-musky character, Moon Drops has eBay snipers on high alert when it comes down the pike. Although Moon Drops came out in 1970, it still has one foot in 1960s perfume baroque (Dioressence, Bat-Sheba, and Bal à Versailles).

With honeyed ripe fruit, spicy florals, and a sensuous base of balsams and woods, Moon Drops is dripping with beauty and complexity. Throughout all this richness I can still smell the sharpness of ylang-ylang and lily of the valley, lifting the perfume back up from sinking into its own decadence.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, gardenia, peach, raspberry, bergamot

Heart notes:

Lily of the valley, rose, jasmine, ylang-ylang, carnation, orris, honey, tuberose

Base notes:

Sandalwood, musk, cedarwood, moss, styrax, amber, benzoin

by MEM Company (1970)

My favorite of the English Leather quad, Wind Drift has a transparency that evokes an Olivia Giacobetti painted from an expressive but sheer palette of olfactory colors, or a minimalist Jo Malone citrus, simple but beautiful. Its little box (I got a group of minis) features a tiny wave, signifying—unlike the mini glade of trees on Timberline, the outline of a citrus fruit on Lime, or the saddle and hat on English Leather—that it will somehow be related to the sea. At its heart, Wind Drift has the scent of wet wood (cedar and sandalwood) surrounded by citrus, herbs, light florals, and subtle musk. For an inexpensive drugstore cologne, this was a charming, restrained little number.

Notes not available.

by Chanel (1971)

Perfumer:

Henri Robert

Chanel No. 19, composed by Henri Robert to commemorate Coco Chanel’s eighty-seventh birthday on August 19, is a masterpiece of restraint. Its song sounds like piano notes played with the damper pedal down. Luxuriant, but not dazzling or bright, Chanel No. 19 is also like semiprecious stones before they’re polished, when their opacity hints at their rawness. Although its strange coldness has prompted reviews that conjure up images of ruthless businesswomen, its earthy, rooty notes suggest a witch in an enchanted forest rather than a bitch in a boardroom.

Chanel No. 19 lurks quietly in dark woods, with muted florals and a hint of fresh-cut leaves and watery cucumber. It has a diluted, earthy, vegetal transparency like freshly sliced root, or moss that has just been unmoored from its base at a tree. It doesn’t release its scent right away.

In an interesting way, it’s what Chanel No. 19 holds back—comforting sweetness, melody, and light—that is its virtue. You wouldn’t ask atonal music for a melody, an herbal tincture for sugar, or a fairy-tale witch for kindness. It’s what we might deem missing from Chanel No. 19 (what is, in fact, its restraint) that makes this a haunting fragrance. The disquieting nature of the top and heart notes subside into a dreamy, comforting base of incredibly subtle leather and woods.

Some of perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena’s minimalist creations seem influenced by Chanel No. 19, particularly his 1992 Bulgari Au Thé Vert Au Parfumée. But where Au Thé Vert is a sunny, happy fragrance, Chanel No. 19 is a moody, poetic one.

A perfume appropriate for casting spells and reading tarot cards, Chanel No. 19 is the empress card, or the evil witch from

Snow White.

Cold, beautiful, and bewitching.

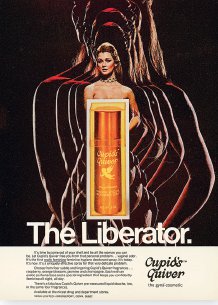

Tawn Limited, “Cupid’s Quiver” (1970)

I

n the late 1960s and early ’70s, advertising for feminine sprays and douches both celebrated the sexual revolution and exploited women’s insecurities. Jacques Guerlain may have claimed in the earlier part of the century that he wanted perfume to “smell like the underside of my mistress,” but now perfumes were being created to hide women’s purported body odors. Cupid’s Quiver spells it out with a directness rarely seen in today’s ads. The problem? Women’s “vaginal odor.” The solution? Deodorant sprays and douches with “exotic perfume” bases and fragrances, including raspberry, jasmine, and champagne. (Champagne?!)

Norforms, “Norforms Antiseptic Deodorant,” 1972

D

oing its best to make women paranoid and hysterical about smelling bad, this Norform vaginal-deodorant suppositories ad suggests that without a suppository to keep “internal odor” away, a woman will (or should?) spend her entire day worrying about how much she’s stinking from within.

(The Chanel No. 19 eau de toilette version is like a ray of sunlight in the dark, damp, eau de parfum forest and features more leather and vetiver.)

Top notes:

Galbanum, neroli, bergamot

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, lily of the valley, iris

Base notes:

Vetiver, sandalwood, leather, musk

by Courrèges (1971)

Perfumer:

Robert Gonnon

French fashion designer André Courrèges was known for his geometric, streamlined, space-age designs replete with goggles, boots, and dangerously high miniskirts. (He and Mary Quant vied for the title of miniskirt inventor.) Empreinte (“Imprint”)—his delicate, melon/peach leather—seems to invoke, however, a 1940s-era woman of mystery rather than a miniskirt-clad Mod scenester.

Once the nose-clearing aldehydes get out of the way, Empreinte becomes herby, fruity, and woody-leathery. It’s one of the most delicate leather scents I’ve ever smelled, disarming my olfactory expectations with its rich peach / light melon / herbs combined with its chypre/amber-leather base. It reminds me of Femme, with its plummy-suede sexiness, and they share some notes, too: peach, plum, jasmine, rose, amber, patchouli, leather, sandalwood.

As it dries down, Empreinte continues to confuse and bewitch with its fresh yet worldly personality. It invites you in with its sweetness and warmth while telling you to keep your distance with its formal chypre/leather structure.

Top notes:

Peach, bergamot, artemisia, aldehyde, coriander

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, orris, melon

Base notes:

Amber, patchouli, cedarwood, sandalwood, oakmoss, castoreum

by Yves Saint Laurent (1971)

Perfumers:

Jacques Polge and Michel Hy

Truly gifted perfumers combine notes in ways that bring out the best in perfume ingredients, and Rive Gauche, thanks to Jacques Polge and Michel Hy, reminds us why rose is such an exemplary note in perfumery.

Like the metallic bottle with its contrast between cold silver and electric cobalt blue, Rive Gauche, the scent, projects a formal, classical elegance (aldehydic floral) underneath whose frozen veneer flows a heartbreakingly beautiful rose. The birch tar and

resins in the vintage provide drama, like a drum roll, or the parting of dark velvet curtains on a stage, which doesn’t exist in the reformulation.

Without this preamble, there isn’t the same shock when the beautiful rose appears center stage. And it is truly radiant, like a movie star in her prime on the red carpet, when you know you’ll never see her looking as beautiful as you saw her that night. The subtle fruit from the peach, the sparkle from the bergamot and aldehydes, and the sheerness of lily of the valley—all of these notes lift Rose up on their shoulders, elevating it and helping it shine.

Drama, contrast, dissonance, surprises, multidimensionality, temporality—this is what has been cut out of the reformulated Rive Gauche. It’s like watching Hitchcock’s

Vertigo

without Technicolor or Bernard Herrmann’s score: an interesting movie, but just 50 percent (if such a thing can be quantified) of what it could be.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, bergamot, leafy green, peach

Heart notes:

Rose, jasmine, geranium, lily of the valley, orris, ylang-ylang

Base notes:

Vetiver, tonka, sandalwood, moss, musk, amber

by Lancôme (1971)

Perfumer:

Robert Gonnon

I love extremes in perfume. If it’s a green fragrance, I want it to be so green as to be bitter and slightly scary. If it’s a floral, I want it indolic, overripe, and decadent. If it’s animalic, I want … well, you get the picture.

My love of extremes can also be satisfied by perfumes that try to do it all and succeed—multitaskers that are able to provide a whole host of extreme notes together in a symphony of excess. Sikkim by Lancôme makes me feel as if I’m getting everything at once: sweetness, freshness, bitterness, richness, spiciness, warmth, and depth—the whole shebang. It starts off mouthwateringly juicy and fresh, moves into a lush floral, and ends on an elegant, dry leather/moss accord.

Like Aramis (1965) and Miss Balmain (1967), but mossier than both, Sikkim combines green and herbaceous top notes with lush florals and a mossy-leathery-ambery drydown that is both sexy and elegant. (Thujone, an ingredient in the hallucination-inducing drink, Absinthe, is listed as a note for both Sikkim and Miss Balmain, and it’s basically a variety of artemisia, which is also a note in Aramis.) This combination provides a roller-coaster ride for your nose—and your brain—because you’re challenged to process these wonderful extremes you wouldn’t find in nature.

Sikkim’s bracing greenness offsets lush gardenia and makes it even sweeter and richer. For the longest time, the gardenia just lingers, its creamy-white petals offered up like a hallucination right in front of your nose. Its chypre-animalic drydown is spicy and mossy, while amber, castoreum, and leather accords create a warming and comforting base.

Sikkim is named after a tiny country in the Himalaya Mountains between Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Tibet that became a state of India in 1974. Sikkim is supposed to have a climate that ranges “from arctic to temperate to tropical as a traveler journeys up or down the lofty Himalayas.” The climate of Sikkim, the perfume, similarly cycles from arctic to temperate to tropical as its wearer travels from its top notes to its base notes.

Notes not available

.