Scent and Subversion (4 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

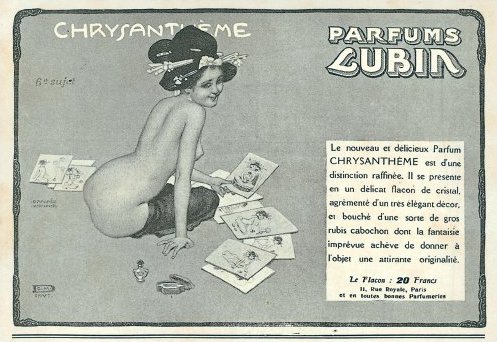

Drawn by artist Raphael Kirchner, this 1913 ad for Lubin’s Chrysanthème was the first luxury perfume brand to advertise in the nudie mags of the time, including

La Vie Parisienne.

Lubin targets men with “kept” women in this ad campaign for Chrysanthème perfume.

by Rallet (1913)

Perfumer:

Ernest Beaux

It has been argued quite convincingly that Bouquet de Catherine is an earlier version of Rallet No. 1 (1923), which itself is an earlier incarnation, give or take a few notes and the quality of ingredients, of Chanel No. 5 (see

pages 35

and

32

).

Notes not available

.

by Paul Poiret (1913)

Perfumer:

Maurice Schaller

In Paul Poiret’s heartbreakingly beautiful Nuit de Chine (“Chinese Night”), a milk-fed peach rests on a spicy, animalic base to produce sensuous, carnal beauty. Persicol (a peach lactone base that was also used to stunning effect in Mitsouko) is overdosed in Nuit de Chine, according to perfume historian Octavian Coifan, and it creates an aromatic and milky peach that could teach some of the cloying fruity notes in today’s perfumes a lesson or two in restraint. (Persicol is also known as aldehyde C-14.)

Notes from

Octavian Coifan:

Jasmine, rose, cinnamon, clove, amber, musk, sandalwood, Persicol or Chuit Naef (special bases at the time)

(1917)

The perfume that launched an entire perfume category, Chypre de Coty, advertisement c. 1949

Perfumer:

François Coty

The chypre that started it all, François Coty’s Chypre was named as an homage to the scents that perfumed the island of Cyprus—an aromatic mix of woods, moss, and citrus. Henceforth, thanks to this groundbreaking perfume, all perfumes in the chypre category have sparkling citrus top notes (usually bergamot) balanced atop a mossy base, with oakmoss and often vetiver, labdanum, and patchouli.

Some classic, early scents can be enjoyed only for their historical notoriety, as the first perfumes that opened the door for later, superior incarnations. But for me, Coty’s Chypre stands alone as an incredibly beautiful and complex scent. At once fresh and herbal, warm and woodsy, and softly floral, Chypre dries down into a powdery, buttery softness. I keep inhaling my wrist for the almost milky richness of what’s left behind, combined with a disquieting hint of civet.

Top notes:

Bergamot

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, lilac, orris

Base notes:

Vanillin, coumarin, oakmoss, patchouli, vetiver, sandalwood, labdanum, styrax, civet, musk

by Guerlain

(1919)

Perfumer:

Jacques Guerlain

A sign of its Orientalism-inspired time, Mitsouko is a French olfactory fantasia named after a character in Claude Farrère’s novel,

The Battle

. Mitsouko falls in love with a British naval officer while married to a Japanese fleet admiral, and decides who she will be with by waiting to see who returns to her alive. But something burns at the heart of Mitsouko that belies its romantic namesake; it’s a perfume that lives in the spiritual as well as the carnal realm.

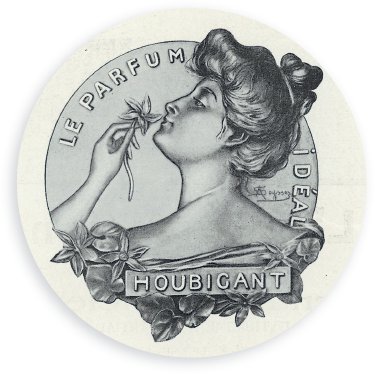

La Parfum Idéal by Houbigant (Advertisement from 1911)

With a sublimely subtle, milky-soft peach heart (courtesy of the rich Persicol note) and spicy cinnamon, clove, and oakmoss nipping at its tail, Mitsouko reminds me of the Japanese incense that burned during meditation sits I did at the San Francisco Zen Center. It is as delicate as spiced tea with a drop of milk.

Meditative, sophisticated, and subtly sensuous, Mitsouko is considered by many to be the holy grail of chypres. Compare the peach in vintage Mitsouko with the fruity cocktails out now if you want to understand how fruit notes in perfume can be sophisticated instead of vulgar.

Top notes:

Bergamot, lemon, mandarin, neroli, peach

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, clove bud, ylang-ylang

Base notes:

Oakmoss, benzoin, sandalwood, cistus, myrrh, cinnamon, musk

by Caron (1919)

Perfumer:

Ernest Daltroff

Ernest Daltroff seems to have specialized in creating perfumes for minxes gone wild. Tabac Blond paid homage to the scandalous bad girls who smoked cigarettes in the 1910s and 1920s, and in its heart is the rich, toasted-caramel smell of rolling tobacco.

Unlike Lanvin’s Scandal, a tobacco scent whose sweet floral notes could be said to reveal that it doesn’t have the courage of its tobacco convictions, Tabac Blond’s tobacco and leather notes aren’t upstaged by florals. It starts off with ylang-ylang and leather, and moves into a wonderful, powdery, yet sharp smoke note that continues to sing through to the vanillic, clovey, spicy, and warm drydown.

Habanita has a comforting, more-legible tobacco presence, and if you want a shocking tobacco scent, look no further than Bandit’s badass wet-ashtray-meets-leather-and-isobutyl quinoline. But in terms of projecting dark, sultry, and yet refined, you can’t do much better than Tabac Blond.

Denyse Beaulieu of the wonderful perfume blog Grain de Musc has written that historically, Tabac Blond for women was “meant to blend with, and cover up, the still-shocking smell of cigarettes: smoking was still thought to be a sign of loose morals.”

Top notes:

Leather, carnation, linden

Heart notes:

Iris, vetiver, ylang-ylang, lime-tree leaf

Base notes:

Cedar, patchouli, vanilla, amber, musk

Notes from

NowSmellThis.com.

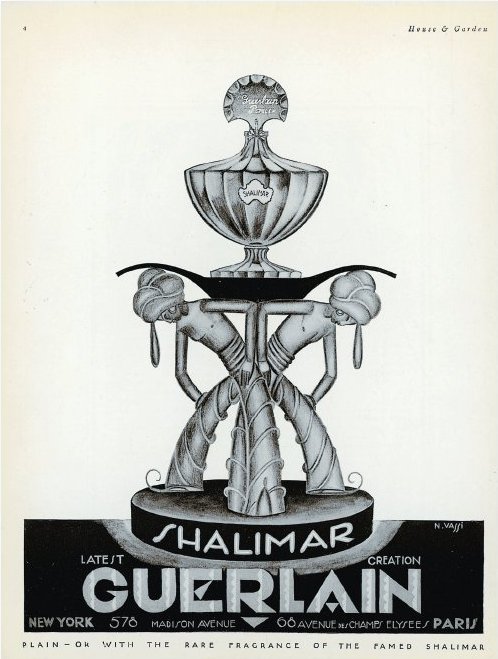

The colonial figure of the “blackamoor,” usually depicting an African man in a turban as a servant, flourished in popular ads, films, and even decorative items like lamps up until the 1970s. In this 1927 advertisement, two highly stylized blackamoors carry a bottle of Shalimar on their backs.

Shalimar, Emeraude, Chanel No. 5 (1920–1929)

L

uxe and decadent with a hint of the disreputable, the feminine fragrances of the 1920s join the Eros of floral notes with the Thanatos of animal-sourced notes, along with tobacco notes evoking the woman of questionable morality who smoked. In short, they redefined femininity outside of the innocent floral. This was the decade of Lanvin’s My Sin; Molinard’s Habanita, originally made to perfume cigarettes; and the groundbreaking Chanel No. 5, created so that women could smell “like women,” and not roses.

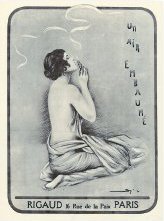

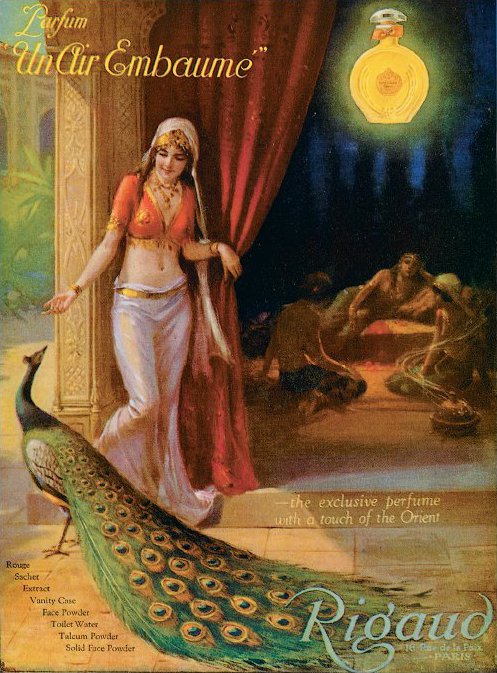

A 1920s advertisement for Un Air Embaumé (“Balmy Air”), by Rigaud

by Chanel

(1921)

“A woman must smell like a woman, and not a rose.”

—

COCO CHANEL

Perfumer:

Ernest Beaux

Perfumer Ernest Beaux got many directives from Coco Chanel for the design house’s first fragrance. Among the qualities Chanel No. 5 was to have: tenacity, versatility, and abstraction. “On a woman,” Chanel said, “a natural scent smells artificial. Perhaps a natural perfume must be created artificially.”

For the other requirement—that it should be a perfume no other perfumer could copy—Beaux complied by using ingredients so expensive that few could have copied them even if they had wanted to; for example, jasmine from Grasse, France; Rose de Mai; and superior ylang-ylang.

What marks Chanel No. 5 as a landmark perfume, however, is its 1 percent overdose of aliphatic aldehydes, the chemical that lends sparkle to fragrances and has been described as fatty, watery, tallowy, like the scent of a snuffed candle. Beaux wanted to use such a strong dose of aldehydes “to let all that richness fly a little.”

Bathed in the golden light of musk and civet, with the crisp edge of aldehydes like the faintest touch of cinnamon or burnt caramel, the florals in Chanel No. 5 come alive, alternately spicy, gourmand, and sensual. Vintage Chanel No. 5 is draped in fur: feminine elegance and restraint plus an animalic extremity. Who knew that an animal lurked beneath its elegant exterior? (See Rallet No. 1 on

page 35

to read about its influence on Chanel No. 5.)

Top notes:

Aldehydes, bergamot, lemon, neroli

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, lily of the valley, orris, ylang-ylang

Base notes:

Vetiver, sandalwood, cedar, vanilla, amber, civet, musk

by Coty (1921)

Perfumer:

François Coty

This drugstore classic is considered by many to be the inspiration for Guerlain’s Shalimar. Initially sharp, aldehydic, and citrusy-resinous, this comforting and haunting fragrance mellows out into a creamy amber/vanilla drydown with a hint of civet.

Top notes:

Orange, bergamot, tarragon

Heart notes:

Jasmine, ylang-ylang, rose, rosewood

Base notes:

Amber, sandalwood, patchouli, opopanax, benzoin, vanilla

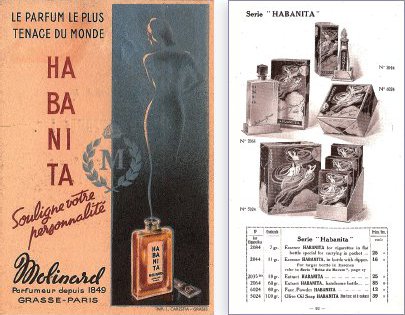

by Molinard (1921)

Originally marketed in 1921 to perfume cigarettes, Habanita came in two forms: scented sachets made to tuck into a pack of cigarettes, or as a liquid you could apply to your cigarettes with a glass rod, to “perfume the smoke with a delicious, lasting aroma.” By 1924, Molinard had turned their scent into a perfume to be worn rather than smoked, but the decadent connotations remained.

Smoky, fruity, and floral notes rest on a base of vanillic, creamy benzoin and leather, making Habanita a complexly comforting scent of sweetness and warmth. A haze of tobacco smoke and the earthiness of leather tie together what starts out sharp (vetiver), gliding later into a jammy sweetness. As the perfume dries down, it smells like the foil that lines a pack of cigarettes.

An advertising trade card for Habanita and a catalog featuring Habanita perfume for cigarettes. Originally marketed in 1921 to perfume cigarettes, Habanita later became a perfume to be worn rather than smoked. (Courtesy of The Farnsworth Collection)

What might at first sniff seem like sensuality in Habanita comes across instead as gourmand, and the tobacco smoke and leather suggest powderiness rather than roughness. So instead of being the dangerous perfume a femme fatale would wear, Habanita signifies comfort—like being stuck in a cafe in Paris on a cold day, comfortably trapped in a room filled with cigarette smoke, an old lady’s violet-scented dusting powder, and the aroma of buttery baked goods.

Top notes:

Vetiver, peach, strawberry, orange blossom

Heart notes:

Rose orientale, ylang-ylang, orris, lilac

Base notes:

Leather, vanilla, cedarwood, benzoin

by Chanel (1922)

Perfumer:

Ernest Beaux

Fizzy, bubbly, and fresh, Chanel No. 22 has the character of a popped bottle of champagne. A precursor to Madame Rochas and White Linen, Chanel No. 22 is one of the best aldehydic florals, those motivational speakers of the perfume world unclouded by darkness and with nary a bad thing to say about anyone.

But this doesn’t mean Chanel No. 22 is uninteresting. Clean, white florals feel overexposed like the whites of surrealist photographer Man Ray’s solarized black-and–white photographs. They are met with scratchy vetiver and incense to give their freshness character, while vanilla warms it all up in the base.

Top notes:

Aldehydes

Heart notes:

Jasmine, tuberose, ylang-ylang, rose

Base notes:

Vetiver, vanilla, incense

by Caron (1922)

Perfumer:

Ernest Daltroff

Perhaps because Nuit de Noël is a perfume that is supposed to evoke the comforts of Christmas, it is one of the few Ernest Daltroff perfumes that doesn’t smell like it needs to go to reform school. Nuit de Noël starts out with a sharp and intense ylang-ylang note, moves into a cinnamony-rose and jasmine heart, and dries down to a spicy comfort scent that evokes mulling spices and the warmth of a room indoors on a wintry day.

Notes:

Rose, jasmine, ylang-ylang, sandalwood, moss, musk

by A. Rallet & Co. (1923),

previously Bouquet of Catherine by A. Rallet & Co. (1913)

Perfumer:

Ernest Beaux

Few people know that Chanel No. 5 is a palimpsest—that is, a text that has been reused or altered, which still carries traces of its earlier incarnation. For perfume historians Philip Kraft, Christine Ledard, and Philip Goutell (as they argue in an article for

Perfume & Flavorist

magazine), Chanel No. 5 is a retweaked version of Ernest Beaux’s earlier Rallet No. 1, which just also happens to be his Bouquet de Catherine (1913) by another name. In a landmark article published in

Perfume & Flavorist

magazine, they concluded that their research showed that the formulas for Rallet No. 1 and Chanel No. 5—both composed by Ernest Beaux—were strikingly similar.

The story behind these multiple renamings and reformulations involves wars, histories, Gabrielle (aka Coco) Chanel’s love life, some royalty, and the inevitable mythologizing and cover-up that makes the idea of Truth with a capital T recede further into the distance.

Before Ernest Beaux was Chanel’s perfumer, he was the perfumer for A. Rallet & Co., a Russian perfumery founded in Moscow in 1843. In 1896 it was bought by Antoine Chiris of Grasse, France, who moved its operations to Paris in 1917, when Russia nationalized its assets. Rallet catered to wealthy Russians, many of whom would come to Paris to shop. To celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of the Romanov dynasty’s rule in Russia, Rallet had Beaux create his first perfume using aldehydes—Bouquet of Catherine (1913)—inspired by Robert Bienamé’s 1912 floral aldehyde, Quelques Fleurs. Unfortunately, war broke out in Europe the next year, and Beaux enlisted with the French army and was conscripted until 1919.

It’s unclear at what point Bouquet of Catherine was rechristened Rallet No. 1, but it was released with that name in 1923. When the Bolsheviks did away with the Imperial Russia that was in power, the Russian market that had purchased Rallet could no longer afford these perfumes, and Beaux had to hawk Rallet No. 1 elsewhere. First stop: Coty. Denied. Then, a fateful introduction between Beaux and Gabrielle Chanel was made through her purported lover, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, an exile from Imperial Russia, and the Chanel No. 5 we know now, with its over-the-top, expensive jasmine, rose, and ylang-ylang, was born as a high-end reformulation of Rallet No. 1.

A wonderful reader gave me a sample from an original Rallet No. 1 bottle. Sniffing it is like recognizing a movie star’s familiar, if less dazzling, sibling.

A promise of the Orient via Un Air Embaumé from Rigaud

(or Russia Leather) by Chanel (1924)

With Russia Leather (also known as Cuir de Russie),Chanel combines a luxurious balsamic creaminess and spice with the animalic smell of leather in a collision this 1941 ad calls paradoxical.

Perfumer:

Ernest Beaux

In this legendary leather perfume, flora and fauna are locked in an erotic embrace, a swirl of floral notes fattened by rich balsams and dirtied by animalic leather. I’m not sure that there’s any vintage perfume that telegraphs opulence and elegant languor quite like Cuir de Russie, once called Russia Leather for the American market. Smoke, leather, and bitter birch tar take the floral notes in Cuir de Russie into a dark, erotic place, but then when the darkness subsides, a decadent ylang-ylang, without its characteristic sharpness but with all its richness, blooms with amber and vanilla. As the vintage dries down, Cuir de Russie toggles between creamy balsamic notes with the undeniable animal of fur and hides. Swoon-worthy.

Top notes:

Orange blossom, bergamot, lemon, mandarin, clary sage

Heart notes:

Orris, carnation, rose, ylang-ylang, jasmine, cedarwood, vetiver

Base notes:

Leather, amber, opopanax, styrax, heliotrope, vanilla