Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 (46 page)

Read Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 Online

Authors: Damien Broderick,Paul di Filippo

“I am never going to let anyone take you from me.”

“Nor I, my dear,” Laurence said, smiling, despite all the complications which he knew might arise if China did object. In his heart, he shared Temeraire’s view of the matter, and he fell asleep almost at once in the security of the slow, deep rushing of Temeraire’s heartbeat, so very much like the endless sound of the sea.

Temeraire does not lack for sexual satisfaction among his own kind. Indeed, his high rank as a Chinese dragon of lofty lineage makes eggs he fertilizes a great prize, especially when he proves to be not just an Imperial but a royal Celestial. Even straitlaced Will manages a difficult love affair with Captain (later Admiral) Jane Roland, mother of his teenage crew member Emily. Even so, there’s a delicate homoerotic (or dracoerotic) undertone to the fierce fondness between man and dragon. It is hilariously brought out by Novik, formerly a well-known slash fiction writer, when Will soothes the sensitive new tendrils sprouting from the adolescent dragon’s ruff:

“Come now, you are like to make everyone think you are a vain creature,” Laurence said, reaching up to pet the waving tendrils….

Temeraire made a small, startled noise, and leaned in towards the stroking. “That feels strange,” he said.

“Am I hurting you? Are they so tender?” Laurence stopped at once, anxious....

Temeraire nudged him a little and said, “No, they do not hurt at all. Pray do it again?” When Laurence very carefully resumed the stroking, Temeraire made an odd purring sort of sound, and abruptly shivered all over. “I think I quite like it,” he added, his eyes growing unfocused and heavy-lidded.

Laurence snatched his hand away. “Oh, Lord,” he said, glancing around in deep embarrassment; thankfully no other dragons or aviators were about at the moment.

Temeraire proves to be of immense value to the embattled British crown, especially when he discovers his gift of the Divine Wind, a terrifying roar capable of raising seas and smashing enemy ships. He finds acceptance and leadership among his fellow war dragons, learning to herd them like the cats they somewhat resemble in character: independent, proud, picky—and, like the dragons of legend, inordinately fond of bling, especially gold, which they seize as prizes in combat or seek to be paid.

In another sense, they are victims of colonial racism, and Laurence’s opposition to the African slave trade also serves to alienate both man and dragon from the corrupt establishment. The books so far published develop all these threads with consummate skill, taking them to Europe, Africa (where they find a dragon kingdom), China (where Temeraire meets his envious brother, and his albino Celestial enemy, the female dragon Lien, while in a brilliant diplomatic

coup

Will is adopted by the Emperor), and finally to the arid wastes of the red heart of Australia.

If there is often one troublesome feature of such alternative histories, it’s that so little is changed by such immensely consequential intrusions—in this case, the introduction of an entire new intelligent species. It’s impossible to suppose, as one can with the allohistories of Roth and Chabon, that one or two small changes can be absorbed without upsetting everything that follows. Finding Admiral Nelson or indeed the British Empire alive and well in such a drastically skewed world is absurd. But then so is faster than light starflight and time travel, so we must put aside such nitpicking qualms and accept the premise, delighting in the pleasures that follow in profusion from that indulgence.

[1]

http://www.temeraire.org/wiki/Main_Page

86

Peter Watts

(2006)

SO A VAMPIRE,

an autistic, a dissociative disorder Gang of Four, a wired man, and a female warrior built like an enhanced carboplatinum brick shit-house walk into a bar. Oh, and don’t forget the AI they rode in on, driving the

Theseus,

their spaceship.

The

Dramatis personae

list of this astonishing novel does sound like a bad joke, but it turns out the bitter joke is on humanity—indeed, on consciousness itself, which is being crushed out of existence across the galaxy. And not by malignant intention, either. Call it evolution in action. This is a voyage of the damned, a ship of tailored anti-fools propelled beyond the edge of the solar system by teleported antimatter, aiming to meet up for the first time with aliens, and test their mettle.

Superb Canadian sf novelist Peter Watts had his own mettle famously tested by US border guards in 2009 as he tried to re-enter his home country, because he failed to throw himself on the ground fast enough, and was beaten, pepper-sprayed, jailed, charged with assault and resisting arrest, and eventually (after TV records were viewed) found guilty only of obstructing a border officer, with a suspended sentence and fine. A year later, he barely survived necrotizing fasciitis, the ghastly “flesh-eating bacteria,” noting, “I’m told I was a few hours away from being dead.... If there was ever a disease fit for a science fiction writer, flesh-eating disease has got to be it.” He contracted it “during the course of getting a skin biopsy… it was being all precautionary and taking proper medical care of myself that nearly got me killed.” His own hard-edged science fiction, beginning with the Rifters trilogy, seems gruesomely like a foreboding parable of these ironic woes.

Blindsight

is a standalone novel.

Watts (who holds a doctorate in marine biology) creates one of sf’s most frightening and horribly plausible alien menaces, and then uses that engine to power a complex investigation of mind, intelligence, consciousness—and the survival consequences of lacking these faculties. It turns out that a mind is not such a terrible thing to lose. Quite the reverse. Our vaunted sense of self proves to be a blockage in the computational pipeline, a decorative feature that gets in the way of swift, effective reaction to the threats and opportunities of an uncaring and mindless universe.

Each of the crew of

Theseus

is neurologically atypical. Siri Keeton lost half his brain after a childhood viral infection and had his cognition rebuilt with computer inlays. Lacking any instinctual empathy or “theory of mind,” he has erected a superb modeling system for grasping, but not sharing, the inner life of other humans. Susan James and her alternative personae are a version of sf’s partials or daemons (see Entry 31), but they pop up from the unconscious to take control at awkward moments. Major Bates operates through drone bodies. Above all is the vampire genius Jukka Sarati, his lethal and terrifying predator gaze masked by wrap-around specs. Vampires were recompiled from the ancient DNA of a species that once preyed on human animals but went extinct because of a neural defect: an inability to deal with +’d lines—the Crucifix glitch. Vampires see all the chains of any argument instantly; they can “hold

simultaneous multiple worldviews

.”

The crew’s mission goal is to examine an incoming comet that seems linked to the event of February 18, 2082, when a grid of 65,536 alien probes blazed above the Earth, taking a global snapshot for their unknown masters. En route, crew in hibernation, the

Theseus

AI is redirected to a target half a light-year from home: Ben, a monstrous dark mass ten time the size of Jupiter, emitting coded pulses. A 30 kilometer craft rises from it, dubbed

Rorschach

for its dark enigma, holding a menace that ultimately spells obliteration to any creature with a mind. These aliens have evolved beyond consciousness, or sidestepped it. They are “philosophical Zombies” achieving perfection in a kind of mindless instant response.

To convey this almost incomprehensible threat, Watts wields his own brand of post-cyberpunk crammed prose, clean and dense, taking no prisoners but playing fair with those who can keep up. When the computerized, autistic narrator is blind-dated with Chelsea, a neuroaestheticist, his best and only friend advises that she’s “Very thigmotactic. Likes all her relationships face-to-face and in the flesh.”

Thigmotactic

implies exactly that: motion in response to touch. But this isn’t showy wordplay, it’s just how such people converse—and it’s a handy way of segueing into the fact that by the end of the 21st century hardly anyone has physical sex anymore. Siri Keeton is “a virgin in the real world,” and not at all distinctive in this. His mother, meanwhile, is Ascended, one of the Virtually Omnipotent, her body stored (maybe, or perhaps recycled) while her consciousness wings off into her own created virtual universe. “Maybe the Singularity happened years ago,” Siri reflects. “We just don’t want to admit we were left behind.”

Everything important is explained, brilliantly foreshadowed, paying off with bangs of shock and abrupt insight. This is the mature fruit of the tree of Swanwick, Greg Bear, Greg Egan discussed in previous entries. Call it neuropunk (as Watts himself suggested). He displays the future with a density that seems cinematic but is more layered than any fractal CGI surface. Simple quotation can’t catch this; the effect’s cumulative. But consider the vile creepy scramblers, all slithery tentacles, that you can never see because they’ve just moved into your visual blind spot:

“…these things can see your nerves firing from across the room, and integrate that into a crypsis strategy, and then send other commands to act on that strategy, and then send other commands to

stop

the motion before your eyes come back online. All in the time it would take a mammalian nerve impulse to make it halfway from your shoulder to your elbow. These things are

fast

, Keeton. Way faster than we could have guessed even from that high-speed whisper line they were using. They’re bloody

superconductors

.”

Blindsight

is one of the jewels of early 21st century sf—like MacLeod’s

The Cassini Division

(Entry 53)

,

it’s another rapture for the nerds, glorying in its knowingness and existential bleakness. Luckily, we readers are not restricted to blindsight (a mysterious unconscious visual skill that lets some blind people without a trace of conscious vision manage to evade obstacles), so we can ponder these portraits of future modified humans and appalling aliens with the same clear-eyed gaze with which Watts addresses them.

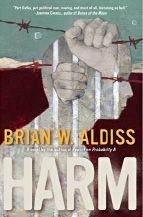

87

Brian Aldiss

(2007)

IT’S THE DAY

after tomorrow in London, and not a pleasant one indeed. With terrorism on the upswing, the authorities have begun rounding up the most unlikely suspects on the flimsiest of charges. One such unfortunate victim is Paul Fadhil Abbas Ali. Born in the UK to immigrant parents, Paul has assimilated to the nines, marrying an Irish wife named Doris, and authoring a novel which he fancies emulates P. G. Wodehouse, that quintessentially British writer. But he’s made one fatal error: in his comedy, two characters joke about assassinating the Prime Minister.