Sea of Ink (3 page)

Authors: Richard Weihe

Tags: #German, #Biographical, #China, #Historical, #Fiction

11

For many months he drew large circles with the heavy brush.

One day the master unexpectedly ordered Xuege to rebuild a derelict monastery complex in a remote spot in the Fengxin mountains.

Xuege devoted himself to this task with all his energy. The renovation of the temple took six years.

The new monastery was called Green Cloud.

From then on he lived in the solitude of the mountains, immersing himself ever deeper in the teachings of the Tao. His responsibilities as the leader of a community of monks prevented him from leaving the Green Cloud for lengthy periods of time, but not from receiving friends and acquaintances as guests.

One evening he went into the pine forest alone. The mountain peaks were glowing in the evening light. It appeared as if a giant had carved them with a huge knife. The flat rocks looked so clean, as if they had been washed. The stream snaked its way upwards, ending in a mere silver thread.

When Xuege spotted a swathe of white flowers along the riverbank he took off his shoes, walked over, bent down and greeted them as if they were children. He had a sudden, burning desire to see all the flowers of Jiangxi in one evening. He ran barefoot across the springy floor of the pine forest; he was dancing with the earth. The light and the pines and the stream and the flowers were there for him alone, and in his happiness Xuege forgot his exhaustion and sorrow, and his heart became as light as a feather.

If you are guided by human feelings you will easily lose your way, a wise saying went, but if you are guided by nature you will rarely go wrong.

Now he had understood.

He finally sat down. The place was so quiet and remote; no monk ever found his way here. He thought: Even if I sat here for three hundred years the mountains would not fall.

A formation of wild geese passed over him like an arrow of feathers seeking to strike desire itself. The stone he was sitting on and the entire ground under him seemed to melt away.

I’d like to live here for the rest of my life, he told himself, until I die on this mountain.

Then he recalled his life as Zhu Da, as a young prince, and he recalled his wife’s black hair and his son’s first smile.

But these images were not memories, rather the dream of a life never lived.

12

The following day he woke with a terrible heaviness in his heart. Somebody seemed to be calling him; he thought he could hear a distant voice but could not understand it. Gripped by an inner urge, he went to his desk, where every day for years he had completed the drawing exercises the master had set him.

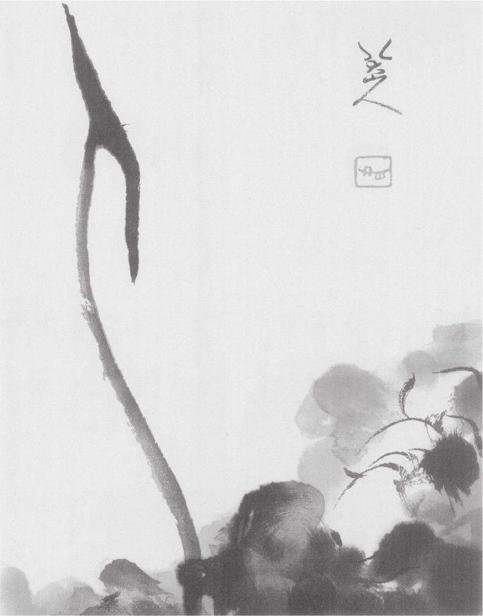

He poured some water into the hollow of the rubbing stone, took the hard block of ink and rubbed it. Then he selected one of his finer brushes and dipped it in.

He had laid a square piece of yellowy-white paper on the desk, which was around four hand’s widths in size. At the lower edge and slightly to the left, he set down the paintbrush, drawing it upwards in a gentle curve, half a finger’s width, which started to the left then changed direction halfway up the paper. A second later he applied a little more pressure to the brush and veered it back to the left. He let this thickened line run to a black point that almost touched the edge of the paper and, without lifting the paintbrush, cocked his wrist, whereupon the tips of the bristles pirouetted; and now the brush glided back down the line in the opposite direction, and beyond onto the blank paper; then with another turn of the wrist he brought his hand down towards himself, lifting the brush from the paper in a slow but fluid movement so that the bottom of his line tapered as evenly as the top had.

And without adding more ink to the brush, he

immediately

covered the bottom third of the paper with

wave-like

shapes stacking up to the right, either with a flick of his wrist or by pressing down his hand to leave black streaks which came out darker or lighter depending on the pressure. Just before the paintbrush ran out of ink he took it to the upper right-hand corner of the paper and, holding it vertically, signed the picture with the name Geshan – single mountain.

Then he put his brush aside. To finish, he printed his seal in red ink beneath the signature.

He went out onto the terrace, gripped the balustrade and closed his eyes.

Geshan had painted his first picture.

After a while he returned to his desk and looked at the lotus flower which had appeared on the paper. Its black-painted bloom looked white and lit up his

signature

in the corner.

Why did he think he could recognize himself in the line of the flower stem and the outlines of the petal?

When he placed his right hand on the white, unpainted part of the paper he noticed that the stem and the lower part of the flower traced the outline of his thumb and wrist almost exactly. With ink he had painted a flower, and with the area he had left blank he had depicted part of his hand.

The flower grew out of the swamp and slime into the air above, there to unfurl its beauty in clear, sharp outlines.

Lotus flower

13

Geshan alias Xuege alias Chuanqi alias Zhu Da brought the lotus flower painting to Master Hongmin for appraisal. He said, ‘I can see that you have grasped much already. You have understood the sense of form and three-dimensional shape; your brush is able to express the curve of the stem and the surface of the petals; it can portray light and colours. You have learnt to see blackness not as an obstacle, but as a source. Here the black depicts a shining white; there, a muted brown or a transparent greenish-blue. You have,

moreover

, made good progress in understanding the essence of things. Your brush suggests some of the floweriness of the flower and the wateriness of the water. That is much already. But there are still lessons you need to learn to master the black ink.’

‘Which ones?’

‘It is not my place to tell you that. You must happen upon it for yourself. But you will know when the right moment has come. That I do not doubt.’

‘Master, give me at least a clue as to how I can improve myself.’

‘You will find all the answers inside yourself. Are you nothing more than a combination of various types and forms of surface? Why should your picture be created only from stiff outer layers that lack all sensibility?’

Geshan gave him an enquiring look. After a while the master added, ‘When you paint you do not speak. But when you have painted, your brush should have said everything. When it has learnt how to speak you will be a Master of the Great Ink.’

14

Geshan had been running the Monastery of the Green Cloud for several years and his reputation as a master of the Tao had spread throughout the entire province. One day the artist Huang Anping paid him a visit to paint his portrait. Geshan agreed on the condition that he could dress up for it.

While Huang prepared to paint and rubbed the ink, Geshan went down to the river. He asked a fisherman to lend him his straw hat and shoes. In the monastery he borrowed a white robe from one of the monks.

He stood before the painter with his hands in front of his chest so that the wide sleeves hung down

heavily

in long folds. His feet were in black sandals and he gazed out sceptically from beneath the broad brim of the fisherman’s hat which covered his head like a huge lotus flower.

The year was 1674.

The Manchus had brought the entire country under their dominion. As they venerated Chinese culture, they tried to win over artists and scholars. The final scattered members of the old dynasty were accorded special recognition by the Manchus.

Huang Anping told all of this to Geshan as they sat together drinking that evening. They decided to disclose the identity of the fisherman in the picture and so, next to his portrait of Geshan, Huang Anping wrote:

Scion of the imperial line of the Ming dynasty.

But how had Huang managed to convey the

imperial

destiny in the facial features of the fisherman? To begin with, the small figure of Geshan stood utterly lost against the empty white background. But Geshan invited special visitors to the Monastery of the Green Cloud to leave behind their seal or a verse on his portrait. His friends Rao Yupu, Peng Wenliang and Cai Shou covered the blank space with their calligraphy, expressing their esteem for the man in the fisherman’s hat. Gradually the background was filled with seals, sayings and testimonies of friendship until they bordered the figure.

15

Geshan discussed with the master the

relationship

between the tall mountain and the small piece of paper, between the hardness of the rock and the softness of the paintbrush.

‘How is it possible to express magnitude through smallness, hardness through softness and light through darkness? How can one thing be expressed by another which it is not?’

‘You need to overcome the contradictions in your mind,’ the master began. ‘Learn to combine them as you do ink and brush. A thing is a thing in relationship to itself, but also in relationship to other things. It is this as well as that. Even if we comprehend the thing only from the perspective of the this, it is nonetheless determined by both this

and

that.’

The master paused for a moment.

‘Do not, therefore, become enslaved by the

perspective

of absolute opposites. This is also that, and that is also this,’ he reiterated. ‘At the point they cease to be in opposition you find the axis of the Path. The Path becomes obscured if you walk down it only one way.’

‘Your words themselves are obscure, Master,’ Geshan said. ‘How does what you say influence the handling of the brush?’

‘For me as a painter the value of the mountain is not in its size, but in the possibility of mastering it with the paintbrush. When you look at a mountain you are seeing a piece of nature. But when you paint a mountain it becomes a mountain. You do not paint its size, you imply it. The importance of the brush lies not in the extent of its bristles, but in the traces it leaves behind. The importance of the ink lies not in the ink, but in the power of expression and mutability of its flow. The importance of the mountain stream lies not in itself, but in its movement; the importance of the mountain lies in its silence.’

Then he continued: ‘Your hand is your guiding spirit. You have everything in your hand. The line that unites is contained in all things.’

And he added: ‘When you dip your paintbrush into the ink, you are dipping it into your soul. And when you guide the paintbrush, it is your spirit guiding it. Without depth and saturation your ink lacks soul; without

guidance

and liveliness your brush lacks spirit. The one thing receives from the other. The stroke receives from the ink, the ink receives from the brush, the brush receives from the wrist and the wrist receives from your guiding spirit. That means mastering the power of both ink and brush.’

16

One day the master summoned him and said, ‘It is important that you paint only with the best ink and the best brushes.’

‘How will I recognize the best ink?’

‘It should breathe in the light like the feathers of a raven and shine like the pupils in a child’s eyes.’

The master invited Geshan to sit down in the middle of the room with his back to the light and instructed him not to move.

‘I will teach you how to spot the difference between everyday ink and superlative ink.’

The abbot disappeared behind a screen. After a while he came back with a piece of paper. Geshan read out loud the sentence the master had just written: ‘

It is not the man who wears the ink down, but the ink that wears the man down

.’

‘Do not think about these words now,’ the master said. ‘Look only at the blackness of the symbols and remember the features of this blackness.’

The master let him ponder this for a while, then

vanished

behind the screen with the paper. Soon afterwards he reappeared with a second piece of paper, on which he had written the same sentence. Now he challenged Geshan to say whether the second sentence had been written with the same ink as the first.

Geshan held the paper up to the light, paying

particular

attention to the characters for ‘man’ and ‘ink’. He was unable to detect any obvious differences in the quality of the ink.

‘Which writing is blacker – the first or the second?’ the master asked.

‘I don’t see a difference,’ Geshan admitted.

The master threw his hands up in the air and exclaimed, ‘One must be an expert to recognize unusual things! To be a painter it is not sufficient to be able to distinguish pebbles from jade and fish eyes from pearls. As a painter you must be able to distinguish black from black; they are very different things! People look at an ink’s blackness only because we require ink to be black, and ink that is not black is surely worthless. That is true. However, if the ink is merely black but not shining, then it appears dull and colourless, and so it is useless. It needs to be both black and shining, and this lustre must shimmer like the surface of the water when the light changes – clear, pure water through which you can see the ground. Then the ink is sublime!’

Without waiting for an answer, the master went behind the screen once more and presented his pupil with a third piece of paper.

‘The blackness of this ink has an almost metallic sheen; it shimmers like varnish,’ Geshan thought as he held the characters close to his eyes. Then he said, ‘That’s a different ink!’

The master leapt up, hurried behind the screen, held the first two pieces of paper in front of Geshan and ripped them up under his nose.

‘You identified it! As you rightly said, there is no

difference

between the first and second pieces of paper. Both of them were painted with the same everyday ink. Characters written in this ink arouse a feeling of displeasure and resistance in the viewer, for they are not really black and they lack any sheen. But for this piece of paper I used the ink of the ink-maker Pan Gu. It is unsurpassed and very difficult to come by. As you identified it, I shall reward you with two balls of his ink. They were given to me years ago by Privy Councillor Han Weisheng and to this day I have never dared use them. Keep them. You yourself will best know when you are ready to use them. Pan Gu’s ink with the stamp of Han Weisheng is properly black. He mixed it with carp gall, which is what gives the ink its silky sheen, and the power of its colour comes from the addition of a little cinnabar and green walnut shells, the precise quantities of which are Pan Gu’s secret.’

After a pause he went on: ‘The man who spends his whole life painting with a single colour must not ignore such differences.’