Sea of Terror

Authors: Stephen Coonts

Tags: #Fiction, #Suspense, #Thriller, #Intelligence Officers, #Political, #Thrillers, #Espionage, #Action & Adventure, #National security, #Government investigators, #Hijacking of ships, #Undercover operations, #Cyberterrorism, #Nuclear terrorism, #Terrorists

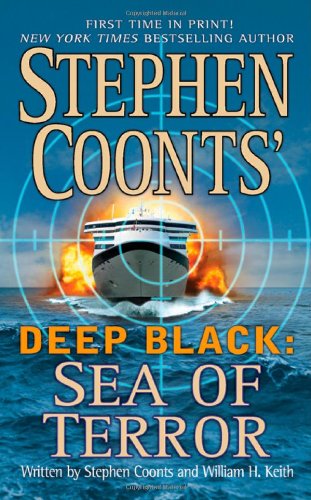

Deep Black: Sea Of Terror

Stephen Coonts

William H. Keith

PROLOGUE:

Pacific Sandpiper Harbor Channel Barrow, England Thursday, 0745 hours GMT

She was a blue and white monster slipping slowly down the deep-water channel on a gray and rainy early-fall morning. To port were the sprawling facilities of the Roosecote Power Station and the neighboring Centrica Gas Terminal at Rampside. To starboard, toward the southwest, was the clawlike hook of Walney Island, the South End. North, blocked at the moment by the towering mountain of the Pacific Sandpiper's superstructure, the port of Barrow-in-Furness slowly receded into the morning haze.

Through his binoculars, Jack Rawlston looked straight across the lowlying strand of Walney Island and could just make out the slender white towers of the BOW on the southwestern horizon, seven kilometers offshore. British Offshore Wind was a joint project of Centrica and a Danish energy group, a wind farm consisting of thirty windmill turbines harvesting ninety megawatts from the winds blowing across the Irish Sea.

Energy. It was all about energy these days. Rawlston stood at his assigned post on the ship's bow, his assault rifle slung over his shoulder as he watched the Walney shoreline creep past. Seabirds wheeled and screeched against the overcast. A foghorn lowed its mournful, deep-throated tone.

And he could just make out another noise behind the normal sounds of the sea. A mile and a half ahead, hoots and honks and bellowing horns sounded in a slowly gathering maritime cacophony that made Rawlston's skin crawl.

Idiots, he thought. As if their pathetic little demonstration could stop us.

He turned to give the blockading line a disdainful look, and added to himself, The bastards wouldn't dare.

A ponderous 104 meters long, with a beam of sixteen meters and a full-load displacement of 7,725 tonnes, the Pacific Sandpiper was one of just three purpose-built oceangoing transports currently owned and operated by Pacific Nuclear Transport Limited, a British firm headquartered in Barrow, in the northwest of England. Her cargo, bolted to the decks in five large and independent storage holds below her long main deck, consisted this September morning of fourteen TN 28 VT transport flasks, each 6.6 meters long and 2.8 meters wide, weighing ninety-eight tonnes and each holding, stored carefully in separate containers, between 80 and 200 kilograms ofmixed plutonium oxides, more colloquially known asMOX.

The fact that plutonium is, weight for weight, the single most poisonous substance known to man, and that there was enough on board the Sandpiper to construct perhaps sixty fair-sized nuclear weapons, did not bother Rawlston in the least. He'd served as security for other PNTL shipments and knew exactly how stringent the safeguards and precautions were. He was one of those safeguards, in fact.

But the demonstration now picking up at the mouth of the channel had him uneasy. What did the fools think they were playing at, anyway?

Less than three kilometers ahead lay the exit of the Barrow Channel into the Irish Sea. From north to south, a half mile of open water separated Roa Island and the southern tip of Rampside from Piel Island in the middle of the channel, and another half mile from the southern tip of Piel to the north-curved tip of Walney. The deep-water channel ran to the right of Piel Island, an utterly flat and grassy bit of land capped by the ruins of Fouldry Castle.

That channel was narrow, only about two hundred yards wide. Spread now along that gap were dozens of small craft, pleasure boats, fishing boats, even a few yachts. They'd been gathering all morning, lining up across the channel entrance. Closer at hand, Zodiac rafts hopped and bumped ahead of churning white wakes as they moved to intercept the slow-moving mountain of the transport.

"Jesus Fucking H. Christ," Jack Rawlston said.

Folding his arms, he leaned against the portside railing forward, watching the show.

Timmy Smithers slung his "long," SAS slang for his SA80 rifle, over his shoulder and joined him from farther aft along the forecastle railing. "Quite a party, huh?"

Rawlston spat over the railing and into the sea. "Fucking idiots," he said.

"Shit, mate," Smithers replied with a grin. He was former Australian SAS, and his words oozed outback affability. "Things just wouldn't be the same if we didn't have our little embarkation party, right? Lets us know they care."

Straightening, Rawlston raised his binoculars to his eyes, massive Zeiss 15 x 45s that snapped even the most distant of the boats into crisp, close-up detail. He'd purchased them on eBay rather than relying on his service-issue set. Several of the larger small craft out there sported banners draped festively from their sides. "STOP NUKE SHIPMENTS," a particularly garish red and green sign read above a crude drawing of a human skull. "NO MOX," read another.

"Pretty wild, ain't it, mate?" Smithers said. "Playing up to CN-bloody-N, I suppose."

"Just so they move the hell out of our way," Rawlston replied after a moment. He focused on a pair of Zodiacs that appeared to be closing with tht Sandpiper off her bow. Each carried two men wearing wet suits, bent low to keep their craft stable as they skipped off the waves.

"Looks like they're siccing the dogs on 'em as we speak," Smithers said, pointing. To starboard, the Sandpiper's escort was leaping ahead, lean and white, a shark to the Piper's lumbering whale. She was the Ishikari of the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force, the numerals 226 prominent on her knife-edged prow.

"Some of them're already inside the exclusion zone," Rawlston said. "Serves 'em bloody right if the Ishi runs 'em down!"

"Yeah, but then if she does, you have all of those lawsuits and demonstrations and newspaper editorials," Smithers replied. "So tiresome."

Rawlston lowered the binoculars and looked at the other man. Like Rawlston, Smithers wore civilian clothing, though the tactical vest, boots, and floppy-brimmed hat were all military issue. As with Rawlston, a small radiation meter hung from his tactical vest. In fact, both men were civilians, but until four years ago Rawlston had been in the British SAS. Now he was a contract employee for Pacific Nuclear Transport Limited, more usually called simply PNTL. He and the twenty-nine other security personnel on board the Sandpiper had been referred to more than once and disparagingly as "rent-a-cops." That, he thought, might be true... but they were very dangerous rent-a-cops, the very, very best that money could buy. PNTL had a great deal riding on these radioactive cargoes, and could not afford to hire anyone who was less than the absolute best.

"There they go!" Smithers shouted, and he gave a whoop. "Run, you green little bastards!" The Ishikari was swinging to port, now, putting herself between the demonstrators and the slow-moving Sandpiper; using her sheer tonnage to clear a path through the line of demonstrators, scattering them. Overhead, a Royal Navy helicopter, a Sea King off the RNS Campbeltown, roared south with a clattering thunder of rotor noise. Under threat from sea and air, the demonstrators appeared to be losing their nerve.

"You'd think," Rawlston said with just a shadow of a smile, "that they'd be happy to see our backs! We're hauling the radioactive crap out of their backyards, after all!"

"Aw, the cobbers're more worried about saving the bloody whales, ain't that right? Don't matter if a city or two gets fried . .. but we can't hurt the whales!"

One of the approaching Zodiacs, Rawlston saw with approval, had been capsized by the Ishikari's surging wake. Raising his binoculars again, he studied the scene with a grin as two wet-suited swimmers floundered in the chop. The occupants of the other Zodiac had been attempting to deploy a large banner reading: "GREENPEACE," no doubt for the benefit of news cameras ashore, but the sudden dunking of their comrades had interrupted the operation.

This sort of thing, Rawlston knew, happened around the world in dozens of other ports. Greenpeace and similar aftti-nuke organizations liked to create demonstrations and photo ops any time a military nuclear vessel put to sea or, as in this case, when radioactive material was being shipped from port to port. These shipments of processed radioactive material had been carried on between Britain and France on one side and Japan on the other since 1995.

PNTL had completed almost two hundred shipments during those fourteen years, with not a single accident, not a single release of radioactivity, not a single hijacking or act of piracy, not a single problem of any type.

But Greenpeace and the others still had to put their tuppence in.

Ishikari was through the channel entrance now, and the Pacific Sandpiper, slowly gathering speed, followed in her wake. Rawlston watched the lines of civilian craft milling about to either side, continuing the honking and tooting of horns, the wail of sirens, the clang of bells. He could hear voices now, chanting, though the distance was too great for him to make out the words.

But the way was open as Pacific Sandpiper nosed through the channel entrance and into the chop of the Irish Sea. The wind was brisker here, kicking up whitecaps beneath the gray scud of the sky.

"At least," he told Smithers, "that's the worst part of the voyage behind us!"

*

Some eighty yards aft of Rawlings and Smithers, the main deckhouse superstructure of the Pacific Sandpiper bulked huge and white above the main deck. On an open wing of the superstructure, high above the main deck, two other men leaned against the railing and watched the demonstrators falling astern.

"Jikan desu yo," one said.

"Hai!"

Both men were Japanese and, so far as anyone else on board the ship was concerned, were representatives of the Japanese utilities company that owned 25 percent of PNTL. They certainly had the requisite papers and ID, though the real Ichiro Wanibuchi and Kiyoshi Kitagawa were now dead, their bodies hidden in two separate Dumpsters on the outskirts of Sellafield, twenty-five miles north of Barrow.

The second man pulled an encrypted satellite phone from his windbreaker, punched a code into its keyboard, and began speaking rapidly into the mouthpiece.

Chapter 1

Royal Sky Line Security Office Southampton, England Thursday, 1127 hours GMT

"my god, Mitchell!" charlie Dean said, shaking his head. "You have got to be freaking kidding!"

"You know better than that, Mr. Dean," Thomas Mitchell said. "MI5 never kids."

Dean was sitting with the three security people at a console at the center of a large room, hanging one floor above the security checkpoint leading from the Royal Sky cruise ship terminal out to the dock. In front of them was a giant flat-screen TV monitor, on which the black-and-white image of a naked man could be seen walking through a broad, white tunnel. To one side, a much smaller security monitor showed the same man, this time from a high angle near the ceiling and in color, wearing dark trousers, a yellow shirt, and a white nylon jacket.

"Yeah," Dean agreed cautiously. "When it comes to a sense of humor, you're worse than the FBI and CIA put together. But since when did you guys turn into pornographic voyeurs?"

"Believe me, Mr. Dean," the woman sitting next to him at the console said. Her name badge bore the name "Lockwood," and she was, Dean knew, a technical specialist with X-Star Security, the company that manufactured the equipment. "There is nothing whatsoever pornographic about this!" She sounded prim and somewhat affronted.

"That's right," David Llewellyn added, grinning. "After the first couple of hundred naked bodies, you don't even notice!"

Thomas Mitchell was an operative with MI5, Great Britain's government bureau handling counterintelligence, counterterrorism, and internal security in general, while David Llewellyn was the head of the Security Department on board the cruise ship Atlantis Queen. Dean had met Mitchell in Washington a week earlier, and knew him to be a dour and somewhat unimaginative British civil servant; he'd met Llewellyn and Lockwood only that morning, when Mitchell had escorted him into the Royal Sky Line's Southampton security section.

"That hardly matters, does it?" Dean said. "It's their privacy at stake, not how many naked people you've seen in your career."

Interesting, Mitchell thought. Llewellyn was seeing bodies. Dean was seeing people.

"I needn't remind you, Mr. Dean," Mitchell said, "that conventional metal detectors simply cannot pick up plastic bottles containing explosives or petrol, hard-nylon knives, or anything else made of plastic. Richard Reid walked through metal detectors several times before he boarded Flight Sixty-three."

Richard Reid had been the infamous "shoe bomber" who'd been subdued by passengers on board an American Airlines Boeing 767 in December of 2001. He'd been trying to light a fuse in one of his shoes, which had been packed with PETN plastic explosives and a triacetone triperoxide detonator. Ever since, airline passengers in the United States had been required to remove their shoes at airport terminal security checkpoints.

Charlie Dean had considerable experience with anti-terrorist security technologies of all types. A senior field officer of the U. S. National Security Agency's top-secret Desk Three, he'd circumvented quite a few of them while on covert missions overseas, and he'd gone through more than his fair share at secure installations back home. In fact, he'd read about this technology some years ago, though he'd never seen it in operation. It was called backscatter X-ray scanning, and it was the latest twist in high-tech security screening ... as well as the most controversial.