Seeing Orange (3 page)

“Pumpkin hasn't been home in three days,” she says. “I called the SPCA. They haven't seen an orange tabby.”

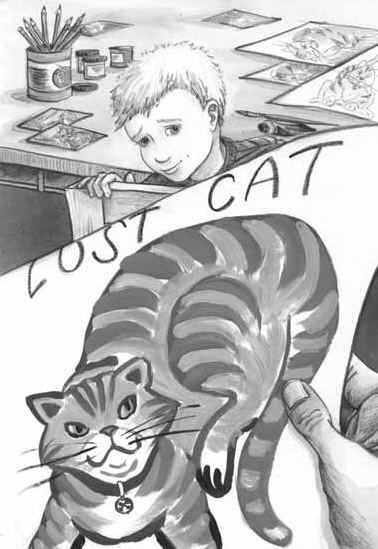

“We need a poster,” Silas says. “You know:

Lost

Cat. Reward.

”

“Good idea,” Mom says. “We need a good photo. One that shows her swirly markings, and the bald patch by her back hip, and her nibbled ear.”

“And her different colored eyes,” Silas says. “One green, the other blue.”

“And her cracked red collar,” Liza says. “With the little tarnished bell.”

“No photo will show all that stuff,” Silas says.

“I could draw a picture,” I say.

“Yes!” Mom says. “Excellent idea. I'll scan it into the computer and print copies.”

“And the reward can be my old iPod cover,”

Liza says.

Mom sets me up at the kitchen table with paper, paints and photos of Pumpkin. It's fun getting the colors of her fur. I mix yellow and red to make orange, and add white and black for different shades. I draw black stripes on her face and the little patch of white on her chin. I use a tomato-soup red for the collar, and mix gold and orange for her bell.

It kind of feels like I'm writing a letter to her. Every stroke of my paintbrush whispers,

Come

home.

I paint her sunning in a square of light on the kitchen floor.

“Marvelous!” Mom says, staring at the painting. “You captured her.

That

is Pumpkin!”

“I wish it

really

was,” I say.

“She'll come home, Leland.”

“When?” I ask.

But Mom doesn't answer. She starts putting the paints away.

“Time for bed, Sweets,” she says after a while.

My heart drops. For once, Mom doesn't know what is going to happen.

I take Pumpkin's food dish outside and make a line of kibbles from the front door, down the front stairs, along the sidewalk to the end of the block. Maybe Pumpkin will smell them and nibble them one by one right to the front door.

On the way to school, we put up posters.

Have

you seen Pumpkin? Reward!

Our phone number is on them. It's raining a little. I hope Pumpkin isn't wet and shivering, wherever she is.

I want to hide under the piano bench until I hear Pumpkin pad into the house to drink from the fish tank. That's what she does! The goldfish get out of her way.

Pumpkin doesn't really

do

a lot. She sleeps most of the time. But she makes our house feel warm. Like a fire in a fireplace. Lions make the jungle a jungle. Pumpkin makes our house a home.

We're going to Goldstream Park today. First, though, we have to write a story about salmon.

I write my title:

Sammen

. I look out the window. Some of the fall leaves are salmon-colored, orangey pink. Salmon get their colors from eating krill, which are pink, and shrimp, which are orange. People can turn orange too, if they eat too many carrots.

Suddenly, I see orange everywhere: the playground slide, the rust on the flagpole, a seagull's webbed feet. I look around the classroom and spy orange letters, orange clothing and orange book covers.

Just thinking about orange made my eyes find it.

“Sammen?” Mr. Carling takes a deep breath. “I spelled salmon for you on the blackboard. S-a-l-m-o-n.”

My face goes numb. I hope I'm turning invisible.

“You had better get some work done, Leland, or you won't be going to Goldstream,” Mr. Carling says. My throat tightens. Delilah walks over and lies at my feet. She thumps her tail against the floor.

Shhh.

“Focus, Leland! Your classmates are almost finished.”

I try hard. I write:

A bald eagle fishes a sammen

salmon from a lagoon. She carries it in her beak and

flies over a schoolyard.

The bell rings. Recess!

“Leland, you need to stay and finish your story.”

I sit back down. I stare at the classroom walls. There are no pictures on them, just the letters of the alphabet and a math chart. The classroom air is like metalâhard and thin. It's the opposite of Yellow House. There, the air is like feathers.

If I could write better, I'd write:

The salmon wriggles

to get free. The eagle can't hold it. The salmon falls

from the sky and crash-lands in the schoolyard below.

Kids crowd around as it flips and flops. Delilah the dog

noses through the crowd and gently takes the salmon in

her teeth. She runs all the way to the ocean with the

salmon in her mouth. She drops the fish into the salty

water and barks goodbye as the fish swims away.

“Well, Leland?” Mr. Carling says.

“My hand hurts,” I say.

“How can it hurt? You've hardly written a thing.”

I try not to cry.

“I write slow,” I say. “Can I draw a picture?”

“Leland, you aren't in grade two to draw pictures,” Mr. Carling says as he unwraps a candy. I would like a candy.

Sammen stink

, I write.

The bell rings. The kids stomp in, big and loud and smelling like the wind.

Mr. Carling lets me go to Goldstream after all. It's a long, bumpy ride on the orange school bus. At the park, a biologist cuts open a dead salmon. She teaches us not to say

Yuck!

but rather,

How

interesting!

The salmon's heart is a deep red-purple. Its liver is purple-brown. Its brain is white! The biologist tells us that a salmon's eye weighs more than its brain does! It makes me wonder if salmon think with their eyes. I sometimes feel that I do.

The biologist holds one of the fish's eyeballs between her thumb and finger, and we take turns looking through it. Everything is upside down! The fish's brain turns everything right-side up again. The biologist says our brains do the same thing.

I go into the woods and lie down along the long trunk of a fallen tree. I stretch my head back so everything is upside down. I just lie there listening, watching the tree branches take root in the blue sky. I close my eyes. The moss and leaves smell good. Then I hear heavy footsteps.

I open my eyes. Mr. Carling is right beside me.

“Leland! Are you hurt?” He speaks quickly.

“I'm fine,” I say.

“Thank goodness,” Mr. Carling says. He wipes his forehead with his hand. Then he asks sharply, “Why are you off the trail?”

I spy a bright piece of garbage in the brush.

“My granola-bar wrapper blew away,” I lie. “I was getting it. Iâ¦I tripped.”

I get up. Mr. Carling brushes dirt and leaves from my jacket.

“We have to catch up to the others,” he says, heading back to the trail. Then he falls.

“Ouch!” he yells. He stays on the ground, rubbing his foot. “Oh. Oh.” He tries to stand and winces.

“Leland, I need you to hurry to the nature house,” he says. He points through the woods, to a building with a red roof. “Tell Madame Maillot that I've twisted my ankle.” Madame Maillot is a teacher that is helping him today. “Tell her I've gone to the bus.” Mr. Carling gives me a serious look. “Don't get lost, Leland. Don't forget what you need to tell Madame Maillot.”

I nod and hurry to the path. I look back once to see Mr. Carling hopping toward the bus. He stops to rest every few hops.

I chant:

Madame Maillot, Madame Maillot

Madame Maillot has got to know

I cross a little bridge. The stream below sounds like xylophone music. I crouch and peer through the slats of the bridge. The water under the bridge wrinkles and unwrinkles as it moves. It never stops. I drop a stick over the rail, then run to the other side and watch it pop out. The stick bobs along. It gets smaller and smaller until I can't see it anymore. I grab a handful of leaves and toss them down. They bounce along on the back of the stream, like little canoes. The stream burbles. I put my hand to my ear to listen. It says:

Madame Maillot, Madame Maillot

I forgot! I run like mad. In the nature house, Madame Maillot is talking to the class. I grab her sleeve. “Not now, Leland,” she says.