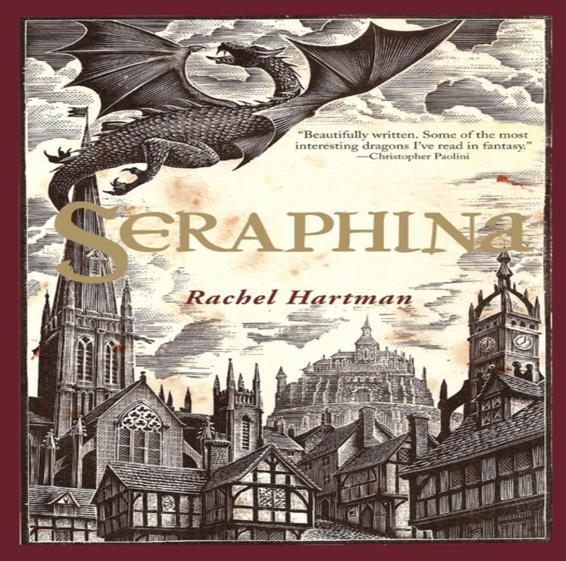

Seraphina

Authors: Rachel Hartman

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by Rachel Hartman

Jacket art copyright © 2012 by Andrew Davidson

Title page illustration copyright © 2012 by Juliana Kolesova

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hartman, Rachel.

Seraphina : a novel / by Rachel Hartman. — 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Summary: In a world where dragons and humans coexist in an uneasy truce and dragons can assume human form, Seraphina, whose mother died giving birth to her, grapples with her own identity amid magical secrets and royal scandals, while she struggles to accept and develop her extraordinary musical talents.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89658-3

[1. Identity—Fiction. 2. Self-actualization (Psychology)—Fiction. 3. Dragons—Fiction. 4. Secrets—Fiction. 5. Music—Fiction. 6. Courts and courtiers—Fiction. 7. Fantasy.] I. Title. PZ7.H26736Se 2012 [Fic]—dc22 2011003015

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

In memoriam: Michael McMechan

.

Dragon, teacher, friend

.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Cast of Characters

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

I

remember being born.

In fact, I remember a time before that. There was no light, but there was music: joints creaking, blood rushing, the heart’s staccato lullaby, a rich symphony of indigestion. Sound enfolded me, and I was safe.

Then my world split open, and I was thrust into a cold and silent brightness. I tried to fill the emptiness with my screams, but the space was too vast. I raged, but there was no going back.

I remember nothing more; I was a baby, however peculiar. Blood and panic meant little to me. I do not recall the horrified midwife, my father weeping, or the priest’s benediction for my mother’s soul.

My mother left me a complicated and burdensome inheritance. My father hid the dreadful details from everyone, including me. He moved us back to Lavondaville, the capital of Goredd, and picked up his law practice where he had dropped it. He invented a more acceptable grade of dead wife for himself. I believed in her like some people believe in Heaven.

I was a finicky baby; I wouldn’t suckle unless the wet nurse sang exactly on pitch. “It has a discriminating ear,” observed Orma, a tall, angular acquaintance of my father’s who came over often in those days. Orma called me “it” as if I were a dog; I was drawn to his aloofness, the way cats gravitate toward people who’d rather avoid them.

He accompanied us to the cathedral one spring morning, where the young priest anointed my wispy hair with lavender oil and told me that in the eyes of Heaven I was as a queen. I bawled like any self-respecting baby; my shrieks echoed up and down the nave. Without bothering to look up from the work he’d brought with him, my father promised to bring me up piously in the faith of Allsaints. The priest handed me my father’s psalter and I dropped it, right on cue. It fell open at the picture of St. Yirtrudis, whose face had been blacked out.

The priest kissed his hand, pinkie raised. “Your psalter still contains the heretic!”

“It’s a very old psalter,” said Papa, not looking up, “and I hate to maim a book.”

“We advise the bibliophilic faithful to paste Yirtrudis’s pages together so this mistake can’t happen.” The priest flipped a page. “Heaven surely meant St. Capiti.”

Papa muttered something about superstitious fakery, just loud enough for the priest to hear. There followed a fierce argument between my father and the priest, but I don’t remember it. I was gazing, transfixed, at a procession of monks passing through the nave. They padded by in soft shoes, a flurry of dark, whispering robes and clicking beads, and took their places in the cathedral’s quire. Seats scraped and creaked; several monks coughed.

They began to sing.

The cathedral, reverberating with masculine song, appeared to expand before my eyes. The sun gleamed through the high windows; gold and crimson bloomed upon the marble floor. The music buoyed my small form, filled and surrounded me, made me larger than myself. It was the answer to a question I had never asked, the way to fill the dread emptiness into which I had been born. I believed—no, I

knew

—I could transcend the vastness and touch the vaulted ceiling with my hand.