Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (17 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

The slow tightening of male sexual freedoms reflected Christian discomfort with all sexual pleasure, even within marriage. Godliness and sex were thought mutually exclusive. “Nothing is filthier than to have sex with your wife as you might with another woman,” wrote Saint Jerome. To early Christian thinkers, all sexual passions were obscene. Constantine repealed Augustus’s laws penalizing men for not marrying, in part to accommodate devout Christians who remained single. Avoiding marriage in service to God was one thing; however, a man who devoted his sexual energies to other men was quite something else. The late Roman Empire would witness a series of convulsive measures against homosexual behavior, with long-lasting effects.

9

CHARIOTS AND SALVATION: HOMOSEXUALITY IN THE LATE ROMAN EMPIRE

About a half-century after Constantine, in 390 AD, a celebrated chariot racer’s penchant for other men would weaken the Roman Empire, humiliate the emperor, and strengthen the political power of the Catholic Church. The charioteer never meant to do anything other than win races, and his sexual tastes were not unusual. But the violent popular response to his imprisonment under one of Rome’s first antihomosexuality laws triggered a bloody chain reaction that ripped across the empire and resonated for centuries.

Male-male sex, long common in the ancient world, was repugnant to the Goth garrison policing the Greek city of Thessalonica, and especially to its commander, Butheric. The Christian-inspired law gave the soldiers the authority they needed to strike out against local practices. The exact charges made against the (supposedly) effeminate chariot racer are unclear. He might have been thrown in jail for something as mild as making a pass at Butheric’s slave, or as grave as homosexual rape. Regardless, his absence left one hundred thousand spectators at the city’s hippodrome without their favorite competitor. The crowd appealed to Butheric to let the charioteer participate in the games, but they were refused. Deprived of their hero, and nursing a deep hatred against the outnumbered Goth barbarians, the Thessalonicans then rampaged violently in the streets.

The mob mutilated Butheric and dragged his remains around the city. When news of the riot reached Emperor Theodosius in Italy, who then further learned that one of his favorite generals had been lynched, he flew into a rage and ordered savage retaliation. Just before the start of the next Thessalonican games, the reinforced garrison locked the hippodrome’s gates and moved in to exact the emperor’s revenge. The soldiers did not bother to distinguish who had been responsible for the riot from who had merely been there for a day’s entertainment. As one Roman historian described it: “All together were cut down in the manner of corn in harvest time.”

In one harrowing recorded vignette from the massacre, a merchant who had brought his two sons to the games begged the soldiers to kill him but spare his children. The Goths agreed to save one of the boys, but the merchant was told to choose between them. “The father, weeping and wailing, beheld both of the two sons and committed to choose neither, but rather continued being bewildered until the time when they were killed, succumbing equally to a love of both.”

At least seven thousand killings later, the soldiers’ work was done. The slashed and beaten bodies of men, women, and children were left strewn around the stadium to rot in the Greek sun. The news of this horrible murder of Roman subjects sent widespread, intense shock waves throughout the empire, in no small part because Theodosius was known for his Christian mercy. The emperor was wracked with remorse, but the deed was done.

Enter Ambrose, the bishop of Milan (and later saint), who was familiar with the emperor’s mood swings as well as the intensity of his present grief. The bishop refused to receive Theodosius personally. Instead, he confronted him with a letter threatening to withhold the Eucharist—and thus the emperor’s salvation—unless he excommunicated himself or did penance. “I dare not offer the sacrifice if you intend to be present,” he wrote. “Is that which is not allowed after shedding the blood of one innocent person, allowed after shedding the blood of many? I do not think so.”

Never before had a church official had the cheek to demand public penance from a Roman emperor. Yet Theodosius had no choice but to submit: His soul was at risk. In an unequalled display of self-abasement, the “Ever-Victorious, Sacred Eternal Augustus, Lord of the World” put down his regalia and could be seen weeping and groaning on the cold stone floor of Milan’s cathedral. After eight months, Theodosius was allowed to take communion, but his soul had been saved at a colossal price: The empire had lost a critical contest of prestige with the church.

Ambrose soon pressed his advantage, pushing Theodosius to step up the repression of paganism and ending any pretense of Roman toleration of pre-Christian religions. In little more than a century, all male homosexual behavior would be officially classified as an offense against the Christian God, and forbidden on pain of death. What had begun as the arrest of a provincial chariot racer resulted, in just a few months, in a turning point in Roman and Christian history. The fate of the nameless charioteer is unknown, but it is a safe bet that his glory days were numbered, as were those of the ancient pagan religions. By enforcing an unpopular sex law, Theodosius subordinated the empire to the church. The crowd that tore Butheric to pieces was of indeterminate religion, but the rioters had been evidently far less troubled by homosexuality than their emperor was—at least when it concerned something as important as the games.

10

Male-male sex had been mostly legal in the Roman world, although powerful cultural norms in Rome (as Greece before it) had long demanded that men of standing take only the active sexual role. Slaves, noncitizens, and other

infames

such as prostitutes were meant to occupy the passive, “womanly” part. Seneca wrote that losing one’s virtue through sexual passivity is “a crime for the free-born” and “a necessity in a slave.” The Latin expression for a male being penetrated was

muliebria patitur

, i.e., “having a woman’s experience.” The word for “man,”

vir

, was not defined merely by physical characteristics. Rather, it meant a Roman male citizen who would never suffer the sexual outrages that were the lot of women and slaves.

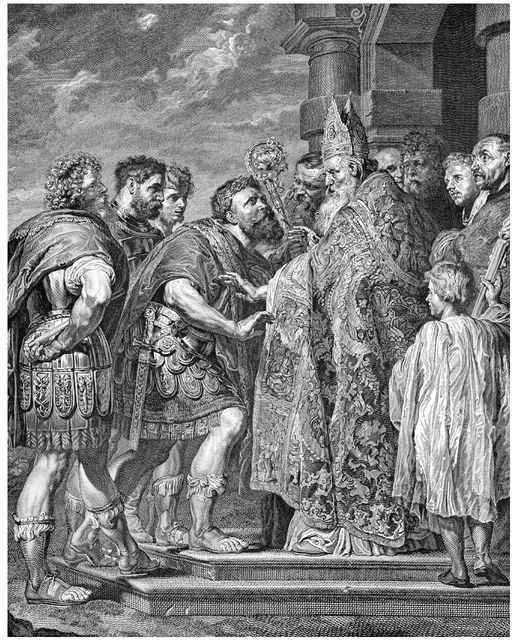

SAINT AMBROSE AND EMPEROR THEODOSIUS

In 390 AD, the popular outcry against the arrest of a beloved gay charioteer set off a violent chain of events that weakened the Roman Empire, humiliated the emperor, and strengthened the power of the Catholic Church. Here, Ambrose refuses to admit Theodosius into the cathedral of Milan because the emperor has enforced Rome’s first antihomosexual laws too vigorously.

©TOPFOTO

Whereas in certain elite strata of Greek society an adolescent boy could maintain a delicate relationship with an older man in which he gave sex in exchange for tutoring and social connections, in Rome it was otherwise: Young male citizens were

never

supposed to be put in a passive position. One of the few scattered homosexuality laws before Theodosius was a ban on pederasty, but only when it involved upper-class boys. Young male citizens wore amulets in the shape of erections to warn everyone that they were off-limits. It was illegal even to follow freeborn boys around in the street.

A Roman citizen could be excused for breaking the law to protect his manliness. As early as 326 BC, the practice of enslavement as settlement of debt was abolished after a magistrate’s son, Titus Ventruius, went broke and was sold to a man who tried to have sex with him. The purchaser had every right to violate Titus, now a slave, but the young man resisted and denounced him to the consuls. The purchaser was then jailed.

11

Two hundred years later, an army officer and nephew of the famous general and consul Gaius Marius was killed by a soldier he had repeatedly tried to seduce. Under most circumstances, the soldier would have been executed, but Marius honored him instead. To condone his nephew’s intention to use the soldier for pleasure would have transformed the latter’s body from an instrument of conquest into something weak—and that Marius could not allow.

HOMOSEXUALITY IN ROME (at least the passive variety) was always shameful, but until the Christian era it was not

illegal

; still, it was practiced often enough. Accusations of passive homosexuality were common but usually harmless insults. Unless the target of the gibe was caught taking a freeborn male against his will, he was probably safe from harsh penalty. Julius Caesar, that paragon of Roman virility and conqueror of Gaul, was popularly believed to have admitted Nicomedes, king of Bithynia, into his backside. His soldiers even chanted in his presence that “Caesar got on top of the Gauls, but Nicomedes got on top of Caesar.” He survived the insult. Caesar’s nephew Octavian (later called Augustus) was accused of submitting to the homosexual desires of his famous uncle—a terrible slur, to be sure, but Octavian’s career was also undimmed. With the exception of Claudius, all of Rome’s first fifteen emperors enjoyed sex with other men. Presumably, some of them were not too fussy about how they did it.

Despite the potential for ridicule, men in the ruling classes followed suit, having sex either discreetly among themselves, openly with prostitutes, or with their slaves. “The poor chap who has to plough his master’s field is less of a slave than the chap who must plough the master himself,” mused Juvenal. It is less clear how many male citizens below the upper ranks shared such views. A humble man is imagined by Quintilian as saying in court: “You rich don’t marry, you only have those toys of yours, those boy slaves that play woman for you.”

With the growing dominance of Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries, however, homosexuality would become illegal as well as shameful. Male-male sex came to be associated with paganism and suffered intense official harassment. Constantine destroyed pagan temples in Phoenicia after the priests there were accused of succumbing to the “foul demon known by the name of Venus . . . where men unworthy of the name forgot the dignity of their sex.” In Egypt, the emperor went further, exterminating a group of river priests on the same charge. Constantine’s sons, Constans and Constantius II, came under the influence of a Christian senator who was passionately opposed to homosexuality. The brother emperors issued a historic decree in 342:

When a man couples as though he were a woman, what can a woman desire who offers herself to men? When sex loses its function, when the crime which is better not to know is committed, when Venus changes her nature, when love is sought and not found, then we command that the laws should rise up, and that the laws should be armed with an avenging sword, so that the shameless ones today and tomorrow may suffer the prescribed penalties.

The wording is obscure, but most historians agree that the “shameless ones” targeted by the law were passive homosexuals. Those inflicting the shame were still in the clear from the state’s avenging sword—at least for a while.

Forty-eight years later, in 390, Theodosius issued the law that ensnared the Thessalonican charioteer. It stated that Rome’s “revenging flames” would consume all those who condemn “their manly body . . . to bear practices reserved for the other sex.” Again, the statute was long on rhetoric and short on specifics, but it is clear that Theodosius was focused mainly on male brothel workers, the only group the law clearly mentioned. Did the emperor mean that active homosexuals should be burned alive as well? Probably not, given that the law still stressed the unnaturalness of a man’s body being used as a woman’s, but it was nevertheless enough for Butheric to arrest the charioteer (who seems to have enjoyed both types of homosexual sex) and unwittingly spark the power plays of Saint Ambrose.

Even with all this Christian fervor, an explicit law against active homosexuality would not come about until 533, when Justinian ruled that those who “perform actions contrary to nature herself” without repentance were to be killed. Homosexuality in all forms was now officially an offense against God. Rome’s punishments were merely the tools of divine will. By this time, Justinian was already executing homosexuals, especially those in the clergy. More than a decade earlier, he had gone on a rampage against rural homosexual bishops. Several were captured and brought to Constantinople, where they were tortured. At least one was castrated and carried around the streets as he bled to death. Death through castration became one of the official penalties against homosexuals of all stripes.

Justinian accepted as true the story that Sodom was destroyed as punishment for the homosexuality supposedly practiced there. He also blamed male-male sex for the earthquakes that shook Constantinople during his reign. But however genuine his belief that he served God by being the “enemy of unmanly lust,” his antihomosexual efforts were plainly vicious and corrupt. Wrote the eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon: