Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (49 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

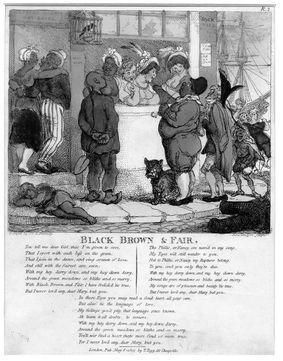

Let those who have never seen a ship of war picture to themselves a very large and very low room with 500 men and probably 300 or 400 women of the vilest description shut up in it, and giving way to every excess of debauchery that the greatest passions of human nature can lead them to, and they see the deck of a gun ship upon the night of her arrival in port.

There were efforts to raise the moral character of soldiers, but they were as ineffective as might be expected—especially as enlisted men were forbidden from marrying. Efforts to enforce the compulsory inspection of soldiers for venereal disease had been abandoned in 1859 because officers feared a backlash from their men. The logical alternative was to focus on the prostitutes who serviced soldiers and sailors, which is what the CDA set out to do.

Under the CDA, police in eleven military towns could force the inspection and treatment of any women they suspected of being diseased prostitutes. If the women refused, they were taken before a magistrate who could lock them in hospitals for three months. In 1869, five additional districts had been added, “detention” times increased, and police powers expanded to make sure that more women were put through the system. The police were allowed to take aggressive measures to enforce the law, in no small part because the law was so vague. The key word in the legislation, “prostitute,” was nowhere defined. As abuses mounted, it became clear that almost any woman could be processed as a prostitute, with all the shame that entailed. As on the Continent, police began to blackmail and intimidate innocents as well as streetwalkers. Moreover, once a woman was put on the list, only a magistrate’s order could get it removed. For the uneducated and the poor, this was almost impossible to accomplish.

In a very short time, the British government had marshaled its regulatory power as a forceful weapon against lower-class women. The soldiers and sailors who used registered prostitutes could take some comfort that they were bedding down with women with “clean” bills of health, but that goal was soon obscured as droves of innocent women found themselves ensnared in a system that robbed them of their freedom and reputations.

On New Year’s Day 1870, the

Daily News

published a letter signed by 140 women, including Josephine Butler and the beloved Florence Nightingale, that attacked the laws on a number of fronts: The CDA condoned the ill-treatment of women while benefiting men, the letter argued; it created state-sanctioned vice; and it was a threat to civil liberties in that excessive powers were granted to police, doctors, and magistrates. The document was the start of a heated, melodramatic conflict that would take another fifteen years to resolve.

Opponents to the CDA were first dismissed as a collection of female cranks and religious zealots, but eventually they gained steam and, in the course of hundreds of demonstrations, publications, and even street battles, grew into a formidable voice for the repeal of the act. The fight was not easy. CDA proponents were every bit as driven as their nemeses. CDA supporters believed it was indecent for women to speak out about sex and state governance at all, much less try to influence legislation. Tempers rose. The deeply religious Butler was no feminist revolutionary (she had formally asked her husband’s permission before taking up the anti-CDA case), but even her religious bona fides did not shield her from violent attack. In 1870, Butler and other repeal advocates spoke out against Henry Storks, a pro-CDA candidate running for office in the military town of Colchester. Butler’s group distributed handbills accusing Storks of endorsing a plan to haul in military wives for humiliating inspections. In response, Storks’s support base (which included brothel-keepers and hired toughs) formed a mob and gave a solid thrashing to Butler’s preferred candidate. Later that night, the crowd surrounded Butler’s hotel and threatened to set it on fire. She escaped out the back door and hid among the food stocks of a sympathetic grocer. During an election a couple of years later in Pontefract, while Butler led a women’s meeting in a hayloft, a gang of paid hooligans set the barn afire. Local police did nothing—Butler and her colleagues escaped being burned alive by jumping through a trapdoor. Her reaction to the attack was telling: “It was not so much the personal violence that we feared as what would have been to any of us

worse than death

; for the indecencies of the men, their gestures, and threats, were what I prefer not to describe” (italics original). For Butler, the immorality of prostitution was nothing next to the “indecencies” of her opponents.

SHIPPING AND RECEIVING

In the nineteenth century, England’s dockside prostitutes became the focus of government efforts to control venereal diseases. In a series of laws called the Contagious Diseases Act, women could be forced to undergo cruel inspections and treatments if they were suspected of being prostitutes. If the women refused, they were subject to imprisonment. The corruption and abuses the laws engendered, especially against lower-class women, galvanized England’s early feminist movement.

©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

In their journals and pamphlets, the pro-repealers told story after heartbreaking story of girls destroyed by the CDA. One pamphlet spoke of a cabaret singer so tormented by police she threw herself into a canal and drowned. To the police, the case was one of simply another dead whore; to the anti-CDA agitators, the girl was one more of God’s children broken on the wheel of an unjust law. At public meetings, the blunt instruments used in medical inspections were displayed to horrified audiences. Women both virtuous and fallen gave witness to what they had endured:

It is awful work; the attitude they push us into first is so disgusting and so painful, and then those monstrous instruments—often they use several. They seem to tear the passage open first with their hands, and examine us, and then they thrust in instruments, and they pull them out and push them in, and they turn and twist them about; and if you cry out they stifle you . . .

BUTLER ALSO WENT for the jugular of hypocritical government officers. She trumpeted the case of one “unfortunate” woman committed to prison by a magistrate. “It did seem hard, ma’am,” the prostitute said, “that the Magistrate on the bench who gave the casting vote for my imprisonment had paid me several shillings a day or two before, in the street, to go with him.”

By 1883, with the help of accumulating data that the CDA was failing to stop the spread of disease, the pro-repealers managed to convince Parliament to suspend compulsory inspections. However, the laws remained on the books, and the battle was far from won. It must be remembered that this issue was being played out at the same time as the age-of-consent drama was unfolding. This Parliament was the same body that had recently

rejected

a proposal raising the age of consent to fourteen. For parliamentarians, any changes to the rules of sexual behavior, especially those that went against their prerogatives to choose any female they wanted, were unacceptable.

By 1885, the issues of CDA repeal, age of consent, and white slavery had become intertwined and doomed to legislative Siberia. There was even a possibility the CDA would be reactivated and extended. It took the convulsive scandals triggered by W. T. Stead’s “Maiden Tribute” articles to push Parliament not only to raise the age of consent but also to repeal the CDA the following year. Anti-CDA activists were bothered by Stead’s methods, but they liked the results. Britain had finally gone out of the legalized prostitution business.

10

THE AMERICAN RESPONSE

American society in the nineteenth century was defined by the multitudes of immigrants spilling onto its shores, whether Chinese laborers in the West or the boatloads of poor Europeans filling New York City’s tenements. The first waves of immigrants were often young men who worked for years in isolation while saving to bring their loved ones over. In the meantime, many sought the solace of prostitutes. On the California frontier, men outnumbered women fifty or a hundred to one during the early years of the Gold Rush, which made life busy for women working the sex trade. Daily shipments of prostitutes sailed to San Francisco from Latin America. In 1849, Patrick Dillon, later the French consul in San Francisco, observed that “weeks never pass that some Chilean or American brig loaded by speculators does not discharge here a cargo of women. This sort of traffic is, they assure me, that which produces at the time the most prompt profits.” Many of the women stayed to work in brothels on the Barbary Coast, but others went on to the mining camps where they adopted names like “Kittie,” “Wicked Alice,” and “Little Gold Dollar.” (One Wichita prostitute called herself “Squirrel-Tooth Alice.”)

Immigrant men were not the only patrons of prostitutes in the United States, of course, but foreign-born women did make up a big part of the sex-worker population. More than half of mid-century prostitutes in New York, for example, came from Ireland and Germany, the two countries supplying the most immigrants at the time. The demand for commercial sex was inexhaustible, and for unsupervised factory girls living in boardinghouses the temptation to make extra money was strong. By 1858 there were an estimated 7,860 prostitutes in New York City alone—one for every 117 people. Hundreds of brothels and saloons with back rooms blanketed the city, each catering to men of particular income levels and tastes. Cigar stores commonly served as fronts for whorehouses, in which the salesgirls were the establishments’ true merchandise. Theaters also served as trysting places. As the house lights were always kept on during performances, everyone could see what everyone else was doing—and there was a lot to see. No one kept still or quiet even in the most respectable theaters, and as audiences hooted and threw food onto the stage, prostitutes serviced clients in the galleries.

Criminality always follows the prostitution trade, and in the United States a visit to a prostitute was a risky affair. Customers in lower-end establishments were often beaten, blackmailed, or simply robbed. Houses were equipped with sliding panels that allowed hands to appear and take customers’ wallets while they were occupied. If a client was well-to-do, the woman’s fake husband or brother would sometimes storm in and demand money. Any man appearing out of place in a low-end brothel could expect to be roughed up, if not attacked, but while customers took their chances, it was the prostitutes themselves who bore the greatest risks. Chinese women working in the famous cribs of San Francisco were no better off than slaves and were often worked until illness and exhaustion killed them. An 1869 story from the

San Francisco Chronicle

described Cooper Alley, the last stop for many:

The place is loathsome in the extreme. On one side is a shelf four feet wide and about a yard above the dirty floor, upon which there are two old rice mats. There is not the first suggestion of furniture in the room . . . When any of the unfortunate harlots is no longer useful and a Chinese physician passes his opinion that her disease is incurable, she is notified that she must die. Led by night to this hole of a “hospital,” she is forced within the door and made to lie down upon the shelf. A cup of water, another of boiled rice, and a little metal oil lamp are placed by her side. Those who have immediate charge of the establishment know how long the oil should last, and when that the limit is reached, they return to the hospital, unbar the door and enter. Generally the woman is dead, either by starvation or by her own hand; but sometimes life is not extinct; the spark yet remains when the “doctors” enter, yet this makes little difference to them. They come for a corpse and never go away without it.

Working conditions for upper-class hookers were better, but the law still placed little value on their lives. In 1836, a beautiful young New York prostitute named Helen Jewett was bludgeoned to death, most likely by the nineteen-year-old socialite Richard Robinson, whose cloak and hatchet were found with her body in a luxurious brothel. Robinson was arrested that day and put on trial for her murder, but he was never really at risk of punishment. Despite the strength of the circumstantial evidence—he was a regular customer of the brothel, and was served champagne in Jewett’s chamber not long before she was found dead—Robinson was acquitted. Most of the testimony came from other prostitutes, and was thus easily disregarded by the jury.

The trial was heavily covered by the penny press and became a topic in the growing national discussion about what to do with “fallen” women and the men who used them. One loud urban missionary, John R. McDowall, focused his efforts on the “silly and inexperienced youth” who visited “these infatuating furies.” Neither McDowall nor his publications would have been noticed much had he not voiced his intention to identify men and boys who visited prostitutes, whom he called “the companions of the polluted.” He also threatened to name men who profited by investing in the sex trade. Ironically, he was brought down on charges of doing exactly what he fought hardest against: A grand jury found that McDowall’s newspaper was “calculated to promote lewdness,” and soon he was convicted of corrupting public morals and committing other acts “too bad to name.”