Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire (8 page)

Read Sex and Punishment: Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire Online

Authors: Eric Berkowitz

The Hebrews expanded the reach of adultery law, but not at the expense of their men’s sexual freedom. Married men were not allowed to have affairs as such, but they were permitted to take as many wives as they pleased—King Solomon reputedly had seven hundred official wives—and also to keep concubines and visit prostitutes. A Jewish man was forbidden from marrying a prostitute, but even on that point the law was rather weak. Unlike other ancient societies, in which a woman was marked as a whore for her entire life once she took up the trade, a prostitute in ancient Palestine could marry a Jewish man if she reformed herself for at least three months.

As for other girls who sought premarital sexual experiences, Jewish law was relatively lenient. A lost maidenhead was gone forever, to the permanent detriment of the girl’s marriage value, but the Bible dictated a simple solution: Unmarried males and females (other than prostitutes) who had sex had to get married. The boy’s family had to pay the girl’s top bride-price (as though she were still a virgin), and the girl’s father had no choice but to accept both the money and the union. The premarital sex would force the father’s hand in granting his consent, but it also required the lovers to live with their decision for the rest of their lives: Divorce between the new husband and wife was forbidden.

Adultery was as much of a challenge to prove for the Hebrews as anywhere else, so they enlisted God’s help. As we have seen, the men of Babylon and Assyria already used the “river ordeal” to determine whether or not their wives had been faithful. Generally, if the women survived a toss in the river, they were considered innocent—the river god had spoken. If they were guilty, the case was closed anyway. The Jews, in turn, focused on the fluids flowing

inside

the bodies of the accused wives. In the only ordeal known to Hebrew law, the Bible requires that a woman accused of infidelity drink “bitter waters.” Her reaction to the beverage would determine her guilt or innocence. This trial of the

sotah

(straying woman) commenced when “feelings of jealousy” washed over a husband “and he suspect[ed] his wife.” The husband would take the woman before a priest, who would then give her a mixture of holy water, dust from the floor of the tabernacle, and the charred remains of a grain offering. “If no other man has slept with you and you have not gone astray and become impure,” the priest would tell the wife, “may this bitter water that brings a curse not harm you.” But if she had been less than pure, the priest had this to say: “May the Lord cause your people to curse and denounce you when he causes your thigh to waste away and your abdomen to swell.” In other words, if you have been messing around, may God show it by tearing your uterus out of your body. The woman would drink the potion, and then . . .

We don’t know what happened next. The Bible tells us that if she was innocent, she would become pregnant, but if she was guilty she would lose her uterus. Presumably she would then be publicly executed like other adulteresses. What is not explained is when and how God would work his justice. As we do not know the chemical makeup of “bitter waters,” we cannot say whether or not any such liquid could have caused a woman’s thigh to “waste away” or her “abdomen to swell.” It seems unlikely.

Moreover, if the woman’s innocence was proven by a later pregnancy, did that mean that her jealous husband was supposed to have sex with her even if she was suspected of being “defiled” by adultery? The text is silent on these critical points as well. However, it says much about protecting husbands when their adultery accusations were proven wrong. Most people in the Near East were punished if they forced others to suffer ordeals needlessly. Hebrew husbands, on the other hand, faced no such risks. Even if their adultery accusations were proven wrong, the men were considered innocent of any wrongdoing. Thus they were permitted to have their wives poisoned time and again on nothing more than a jealous hunch.

16

TREMBLING BEFORE GOD: HOMOSEXUALITY AMONG THE HEBREWS

With the exception of requiring husbands to be faithful to their wives—at least in theory—the Hebrews treated adultery much as their neighbors did. They struck out on their own, however, in designating a new sexual “abomination” where there had been no precedent: The Bible made anal sex between men a crime of the worst order, for which death by stoning became the only option. “Do not lie with a man as one lies with a woman; that is detestable,” commands Leviticus. “Their blood will be on their own heads.” Men had been “lying together” since the beginning of civilization, of course. This was the first time they risked their lives by doing so.

The Code of Hammurabi, which ordered society in most of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley for more than a thousand years, has nothing to say about homosexuality. The laws of Eshunna and Egypt are also silent on the subject. The Hittites forbade father-son relations, but that was part of a general rule against incest. The Assyrians thought it shameful for a man to repeatedly offer himself to other men, and also prohibited men from raping males of the same social class, but all other male-male sexual relations were ignored. The Hebrews, by contrast, made no distinctions and left no exceptions. Sexual intercourse between men was out, regardless of who was doing it and how it was done. The Jewish God hated it so much he wrecked the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah to prove it.

But before that story (and here’s the punchline: It’s not true), it is worth looking briefly at why the Hebrews would have adopted such a position. As we saw earlier, the ancient Jews were consumed with a sense of physical vulnerability, which they translated into spiritual terms. By drawing rigid sexual boundaries, the Jews were trying to bulk up the body politic. Men having sex with men blurred the lines by putting males in the “receptive” role of females in sex acts that, like bestiality, produced no children. Sexual pleasure was never forbidden among the Hebrews so long as it occurred while husbands and wives were producing

more

Hebrews. When they sought erotic pleasure for its own sake, or when they had sex that resulted in illegitimate children (as in cases of adultery or incest), the nation of Israel as a whole was weakened.

17

God threatened to destroy the Jews: If they enfeebled themselves from within, they would be destroyed from without.

In this context, biblical antihomosexual laws were also instruments of foreign policy. Male-male sex was forbidden (the scriptures ignore lesbian relations) precisely because the Jews’ neighbors permitted it. Just as sex with animals was common in the region, so was a benign attitude toward same-gender sex. As it was the mission of the Jews, based on the commandment of their God, to “not do as they do” in other, non-Jewish societies, homosexual sex was just one of a litany of “filthy foreign” practices the Jews defined themselves by rejecting.

18

If the Hebrews’ enemies permitted homosexuality, it was inevitable that Jewish law would forbid it.

The book of Leviticus was supposed to come to Moses directly from the mouth of God, so its threats of destruction for homosexual sex were taken, so to speak, as gospel. But a simple law is rarely enough in itself to change people’s behavior. The point needed to be driven home with a gruesome example of God making good on his threat. Oddly, the Bible provides no such illustrations. In a book crammed with anecdotes, allegories, and repetitions, the subject of homosexuality is addressed just twice, and in the comparatively dry language cited above. To fill the gap, some later scholars decided to recast the old Genesis story about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The effort was forced, to say the least—there is no evidence that either of those cities was a hotbed of homosexual sex—but it was very successful in the end. The tale of these two accursed cities became history’s single most influential myth to transmit antihomosexual prejudice.

Abraham’s nephew Lot was a resident of Sodom, a locale known, along with Gomorrah, as one of the evil “Cities of the Plain.” News of the cities’ wickedness reached God, who sent two angels in the guise of foreign travelers to investigate. Lot offered them lodging for the night, but their presence in his house agitated the townspeople. Before the angels retired for the night, a mob of men gathered outside Lot’s house. They demanded to see the travelers “that we may know them.” Lot refused, which enraged the mob even more. The key to this part of the story is the meaning of the word “know” (

ve’nida’ah

in the original Hebrew text). Did the word mean simply “to become acquainted with,” as many scholars argue? Or did it directly imply sex? Were the townspeople demanding only to look the visitors over, or did they want to rape them? It is impossible to say, especially given Lot’s response: “I have two daughters who have never slept with a man. Let me bring them out to you, and you can do what you like with them. But don’t do anything to these men, for they have come under the protection of my roof.” The crowd was not interested in deflowering Lot’s daughters; they wanted to “know” his guests. As they surged forward to break down Lot’s door, the angels struck them all with blindness. The next morning, Lot fled with his family, and God rained down fire and brimstone on Sodom and Gomorrah, destroying these cities forever.

There is general agreement today that the Sodom mob’s crime was to ignore the custom of providing hospitality to strangers. By housing and protecting the two angels, Lot was doing what any decent Bronze Age Near Eastern host would do. The mob’s unruly demands to “know” the disguised angels were worse than rude, even if they had no intention of “knowing” the strangers carnally. But truth has never gotten in the way of a good story, and it did not take people long to turn this passage into a cautionary tale against homosexuality. The Jews themselves seem to have been the first to do so when, in the first century AD, they were horrified at all the homosexual sex going on among the Greeks and Romans. The reinterpreted story was soon swallowed whole by the Christian church, and thereafter became the basis of history’s most virulent antihomosexual laws. As early as the sixth century AD, the (Christian) Byzantine emperor Justinian pointed to Sodom and Gomorrah as the reason for his persecution of homosexuals. “Because of such offenses,” went one of Justinian’s laws, “famine, earthquakes, and pestilence occur.”

BY THE MIDDLE Ages, the word “sodomy” had come to encompass not only male-male sex, but also an ever-shifting list of forbidden sexual practices. Occasionally, lesbian sex was included in the definition, and when it was, lawmakers made sure to tie it back to the supposed debauchery of Sodom and Gomorrah: The “mothers of lust,” as the women of those cities were called, could not be satisfied with men, so they turned to other women. While sodomy was defined differently everywhere, the example of God’s wrath against the two cities was viewed as justifying the cruelest possible treatment of sodomites. “[I]t is well known how much the sin of sodomy is detested by Our God,” said Venice’s ruling Council of Ten in 1407, “since it was the reason that he destroyed and ruined by his last judgment cities and peoples in which they [sodomites] lived.”

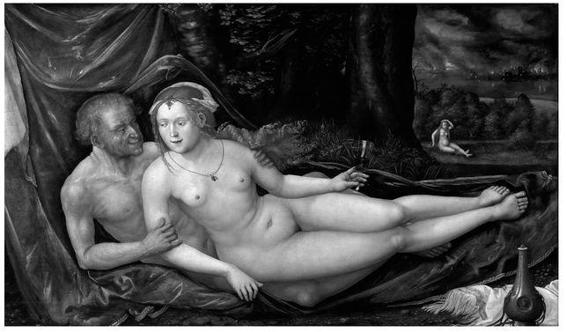

LOT AND HIS DAUGHTERS

The biblical story of Lot, who tried to protect two angels from the bad people of Sodom, has been invoked time and again to support antihomosexual laws. Yet gay sex had nothing to do with the story. Lost in all the talk of fire and brimstone was Lot’s invitation to his townsmen to rape his virgin daughters. Later, when Lot and the girls were hiding in a cave, they got their father drunk and had sex with him.

©TOPFOTO

The myth of Sodom and Gomorrah was picked up by England’s most important legal authority, William Blackstone, who commented, in the eighteenth century, that “the infamous crime against nature” was a “disgrace” so revolting that it should “not . . . be named among Christians,” and should be punished by death, as God had shown his disfavor by working “the destruction of two cities by fire from heaven.” Modern American courts have been no less ready to embrace the story as truth. One Alabama court dealing with a 1966 sodomy case wrote: “We cannot think upon the sordid facts contained in this record without being reminded of the savage horror practiced by the dwellers of ancient Sodom from which this crime was nominally derived.” In 1968, the North Carolina Supreme Court, when passing on charges against a man for homosexual sex, referred to the “famous Biblical lore in the story of the destruction by fire and brimstone of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah where the practice was prevalent.” By this time there was, of course, doubt as to how the two cities were destroyed, but there was still total certainty that “the practice” of sodomy was the cause of God’s anger.

19