Sex for America: Politically Inspired Erotica (21 page)

Read Sex for America: Politically Inspired Erotica Online

Authors: Stephen Elliott

BOOK: Sex for America: Politically Inspired Erotica

6.58Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Two years and two months ago she gave birth. Her own boy has long since been weaned, sent back to America to live with relatives. On orders from her government, she kept the milk flow- ing until she could infiltrate their tribe. She sleeps in a hut the soldiers have lovingly built for her, with a floor of matted straw. They feed her palm wine and coconuts and small animals they have killed and roasted. The meat tastes of fire and of the sticks on which it is skewered.

She loves the heft of her breasts before nursing, the way the milk fills her until the skin stretches tight. When she hears them treading the path to her hut over dead branches and fallen leaves, two at a time, her breasts tingle in anticipation, the nipples tighten, her shirt is soaked with warm milk.

What she did not expect, what has come as a complete sur- prise, is the bliss: theirs and hers. The way a grown man’s eyes will look hungry and sometimes mean as he latches on, but will roll back in his head as he drinks his fill, infantile. The way she becomes damp and needy, opening her legs to allow their bare knees to press against her. She rocks back and forth against them while they nurse, glad for the fact that her government’s technology doesn’t reach here, into the heart of the forest. She is certain the men in their brightly lit offices would find her lust unbecoming, unnecessary, at odds with the spirit of her mission.

Sometimes the men suck themselves into a state of half- conscious ecstasy, the milk dribbling out of the corners of their mouths. Sometimes they ejaculate while drinking. Sometimes she does, too, dreaming of God and country, her own bright sacrifice.

Sometimes they bite down and their teeth leave marks. There is a certain one who always draws blood, every time. She thinks of him during the day while she lies alone in her hut, waiting. She would like to kiss him afterward, would like to taste her milk on his tongue, the sweet-sour tang of it.

Late at night, after nursing, they fuck her, two at a time: one with his cock, the other with his hand. She has never been fucked so beautifully and so desperately as these men fuck her, dreaming, perhaps, of their wives and mothers. She, meanwhile, thinks of her son back home with her family. By now he must be speaking in sentences, and learning the alphabet. She is proud that he will grow up in an omnipotent country, an empire uncompromised by the whims of smaller nations; she hopes that he will understand her own small contribution.

Unbeknownst to the guerillas, she has been ingesting a toxic chemical substance which, upon entering her body, concentrates itself in her milk. Each night, after the men have left her hut, she injects herself with an antidote. It will not keep her safe forever, but it will keep her alive long enough to complete her work. It is important work, her government assures her. Necessary work. Work only a woman can do.

A few of the soldiers have already begun to show signs of illness—the characteristic yellow eyes and swollen glands, the deteriorating joints. Believing it is some mosquito-borne disease,

they treat it with useless medicines, dress the joints with pointless salves. And still they come to her, mouths agape with hunger and lust, blind to the traitor in their midst. Still they fuck her with a passion completely beyond any she has known before. Even the father of her son was temperate in comparison, filling her with his sperm casually, noncommittally, on the night they met. It hap- pened at a party, in the bathroom. He shoved her against the wall; he did not take off his clothes.

So unlike these men, who trust her with their bare skin, their unfathomable hope. She is touched by their faith, awed by the power of their mythology: that they could invest someone like her, so ordinary in every way, with such power.

She is not alone. She does not know how many others like her are scattered among the hills and forests. Every one of them is an unwed mother. Every one of them has been persuaded that this is the way to make amends, to save her family’s honor and make her country proud. She imagines that one day books will be written about her kind. There will be documentaries, posthumous praise. Medals of honor are not out of the question. Maybe some of the women will even survive to tell their stories. She knows she will not be one of them. Lately, her body has succumbed to strange pains; she feels sometimes as though a place is being hollowed out inside her, in the vicinity of her kidneys. She can almost feel some- thing there, like a small and hungry animal gnawing away.

She has a secret hope: that one day her son will visit this country, retrace the steps of the soldiers, and find the place where she is buried, her place among the men.

SOCIAL CONTRACT

STEPHEN ELLIOTT

“You have the right to bear arms,” she says, slipping the

ropes through my fingers, and then around my elbows, pinning them painfully together and cinching them through the window handle above my head. “Just not these arms.”

Her skin is the color of pasta. She has large cheeks, a careful mouth. “Harry Truman invented the national security state,” she says, my right leg pulled at the ankle by a long cord that finally connects at the base of a radiator. My other leg is spread, the rope looped around the refrigerator. My legs are akimbo, my body utterly vulnerable. “The people have to be afraid, Truman said. That was the way Harry Truman thought. We have to fear the communists. Franklin Roosevelt was dead. Long live Franklin Roosevelt.”

The nipple clamps hurt. The ball gag she has stuffed into my mouth makes it impossible for me to answer her, if there was an answer to be given. She didn’t ask me if I wanted this. She’s stron- ger than me, especially since my accident. I never fight her any- more. She does what she wants.

“The Geneva Convention holds that you can’t torture prison- ers. America is a signatory to the Geneva Convention. Are you a prisoner?” I nod my head. She closes my nose shut with two fingers. I can’t breathe through the gag she has forced into my mouth. There is a moment of peace. This is it, I think. I am going to die. And then my body starts to flop, the panic coming through me involuntarily, and she’s laughing, and she lets go of my nose, and the air rushes into my body in deep, sweeping breaths, and her laughter fills the room with its cruelty.

“We don’t care about treaties,” she says. “Hitler didn’t care about Versailles and they gave him Czechoslovakia, the Rhine- land, and Austria. Anschluss. That’s what they call it. But Hitler had his problems. Repressed homosexual.” Her hand runs along my stomach and the top of my leg and then down beneath me, her finger touching my anus. “Are you a repressed homosexual? You don’t seem to like sex very much. I think you are.” I feel her finger slip slightly into my anus and then out. “So he died in a bombed-out bunker in Berlin in 1945, with his new wife. What the hell for?” I watch as she stands and walks to the closet and dips through the door, rummaging through the sound of paper bags. She has such long legs. She’s a cyclist. Her long thin body is knotty with strips of muscles. Then she’s in front of me, between my legs, looking gleefully into my eyes, forcing something large into my ass. I scream into the gag, a muffled gasp, a blunt, dulled

shriek. Whatever it is goes in and it burns and it stays there, throbbing slowly. The pain begins to subside. But she still has something in her hand and she squeezes it and an electric shock shoots through my bowels, my eyes bulging in my face, my body pouring sweat onto the sheets.

“I was wondering if that would work.”

She smiles, warmly, happy and content. It’s been twelve years now since the first day we met. A couple of waiters in a young restaurant on the edge of the city, working to make ends meet. We didn’t know what we had.

“We don’t care about treaties,” she continues. “In 1954 Eisen- hower signed a treaty that provided for free elections in Vietnam in two years’ time. But when it came due he changed his mind. He said if Vietnam had free elections, Ho Chi Minh would receive eighty percent of the vote. And that wouldn’t be good for America. So much for democracy. Do you feel cheated? Look at the Irani- ans. The Shah served us well for twenty-five years. Then they took hostages.” She steps forward, her naked foot on my stomach. She walks over me and then places her foot on my face. She rubs her foot over my face, back and forth, across my nose. She steps on the clamp on my nipple, and I let out another involuntary dull scream. “Cheated by our vows to have and to hold, to love and to cherish, to protect, till death do us part. Do you think we’ve parted too early? Did you think things would be different when you pledged your allegiance in school, and at the baseball games? That your country would protect you while the bombs fell and U.S.-installed dictators sent death squads into the villages of South and Central America to kill the women and children first? Here is your democ- racy.” Her foot presses hard on my face, and my nose hurts. I think

it’s going to break. With the heel of her foot she pushes the gag farther toward the back of my throat. Tears spring from my eyes, soaking the fabric around my ears. “You should be able to answer some of my questions. You should.

“I’m not blaming America,” she says, sitting heavily on my chest and then turning around, facing away from me. Her long back, straight and proud, the bulb of spine and her dark hair which she’s taken to wearing short. She’s wrapped a chain around my penis and balls and she’s slowly making it tighter. “I was born here, same as you. I’m not blaming anybody. It’s just that you have the right to remain silent, and maybe the Republicans really did win the election, and maybe they didn’t. It’s too close to call. Both sides believed in three strikes, you’re out. Life sentence, no parole. How many strikes do you have?” she asks, turning her head to me briefly and then going back to her task. “There’s no welfare here. You’ll have to work for what you get.”

I’ve surrendered myself to the continuous pain. I’ve allowed the pain running through my body to numb my mind. This is my wife. This is what we have. Who would have thought we would have lived in this apartment all this time.

“And then the wars came.” Another shock rings through the electric plug in my ass, pain striking through me, her hand in my hair pulling hard, her other along my ribs, buckling forward as if she were riding a horse, her feet sliding back toward my cheeks. And then stopping. She’s loosening the chains. Gently wrapping her thumb and forefinger around my penis and balls. “And they flew planes into our buildings and our buildings crumpled and fell to the ground. We have to defend ourselves. They would have

done it anyway, whether we deserved it or not. That’s the way people are. And the president didn’t want to consult Congress any- more. He asked them to dissolve themselves, to remove themselves from the conflict. And of course they did. Self-preservation in the face of terror.

She slides her body back, so her ass is just in front of my nose, the smell of her and her flesh totaling my vision.

“Do you remember Bukharin?” she asks. “It was 1936, and he confessed in a public address to the people. He turned on his fellow Bolsheviks, Kamenev, Trotsky, Zinoviev, all Jews. He wanted to save himself. But Stalin placed him under house arrest anyway.

Koba, why do you need me to die?

he asked in his unanswered letter to Stalin. But who was he to ask for forgiveness? All of the original Bolsheviks subscribed to a doctrine of terror, of starving their own people. It was merely the rooster coming home to roost.” Her hand is in my mouth, fishing out the gag, plucking it from between my cheeks. She rubs her fingers inside my lips, massaging my gums. And she’s right, I breathe so much easier now. She undoes the rope at my ankles, and my knees slide together, my legs bending on their own will. She undoes my hands from the window and releases my elbows but keeps my hands tied together. My hands tied, I curl into a ball, pulling the tear-soaked sheet with me. And she curls behind me, her body circling my body, her knees forcing between my knees, one hand underneath my head and across my chest, the other between my legs, gripping my pe- nis. I can feel her body, her strength which seems to increase every day even as mine declines. Her body is so firm, intent, and purposeful.

“My darling,” she says, a whisper, her voice like the cars on the street, penetrating into the darkness. Thank God for the eve- nings, when the sun is down. “I’ll protect you.” Her breath swim- ming across my ear, searching through my hair. “You don’t have to worry. Never worry. Never ever worry again. I am here. I will keep you safe.”

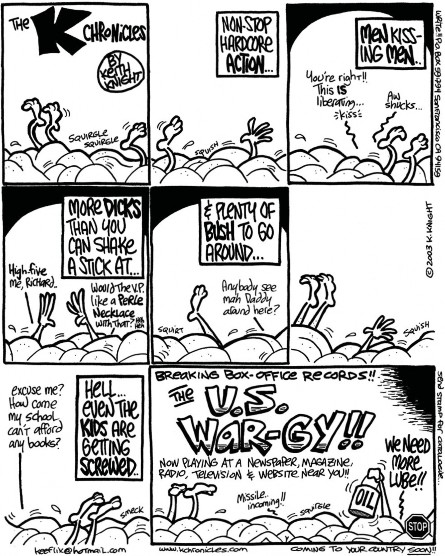

WARGY AND ENERGY POLICY

KEITH KNIGHT

Other books

Funeral with a View by Schiariti, Matt

Suited to be a Cowboy by Nelson, Lorraine

Seeing Black by Sidney Halston

The Chase by Lauren Hawkeye

American Indian Trickster Tales (Myths and Legends) by Richard Erdoes, Alfonso Ortiz

Conan: Road of Kings by Karl Edward Wagner

The Invisibles by Cecilia Galante

Heart of Hurricane by Ginna Gray

The Rebel’s Daughter by Anita Seymour