Sexuality, Magic and Perversion (10 page)

Read Sexuality, Magic and Perversion Online

Authors: Francis King

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Counter Culture, #20th Century, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

The second characteristic of fertility-based religion—the belief that

time is non-linear—arose from the fertility cycle itself. Time was conceived of not as a linear progression from point A to point B but as a circle ending in its own beginning; western man sees time as an evolutionary ladder with himself standing on its topmost rung; his primitive ancestors saw time as a serpent biting its own tail. This cyclical conception of time was a necessary product of fertility itself; for all those who have lived in close contact with nature have inevitably become aware of the cyclical pattern of the reproductive process. In temperate climates producing one crop a year the nature of the seasonal pattern was apparent; seed germinated in the spring, the plants grew in the summer, ripened in the autumn, died in the winter, and then, in the spring, the whole cycle began again with fresh life springing from the “dead” husks of the old. Even in non-temperate climates, where the progression of the seasons was by no means so easily observed, man became aware of similar cyclical patterns—the alternation of “dry” and “monsoon period”, the return of the “heliacal rising” of some star, or the complexities of the lunar cycle. This last, which requires extremely sophisticated observation,

3

was of particular interest because of the supposed correlation between the twenty-eight day “full moon to full moon” cycle and the menstrual cycle of the human female.

For technological urban man it is easy to see the fertility cycle as a mere series of easily explained natural phenomena but primitive man conceived of it as a product of the personalised and hierarchic structure of nature itself; for nature was regarded as having some features in common with humanity, as being approachable by and communicable with mankind, and as being hierarchic, in that it was made up of a hierarchy of spiritual entities extending downwards from the “sky father” and the “earth mother” to the minor godlets of springs, trees and rivers.

The fourth characteristic of all fertility cults—a belief in the law of cause and effect—was a necessary corollary of and depended upon, the second and third characteristics I have previously described. The fertility cycle was not seen as an event that “just happened”, but as being caused by (and its continuance depending upon) the benevolent intervention of the many non-human entities who made up the hierarchy of nature. Thus either crop-failure or the sterility of man and/or beast

were never considered to be the result of “natural disasters”, instead they were seen as the results of supernatural powers deliberately with-holding the gift of life.

From the belief in supernatural forces as the causative factors in the fertility cycle sprang much of primitive magic and religion,

4

for the function of both these was largely the affecting of nature by either placating or manipulating the beings that controlled it.

The overall symbolism of primitive fertility cults was often directly derived from the act of human copulation; the “sky father”

5

and other gods were represented as ithyphallic (i.e. with erect penis) and the “earth-mother” was often shown as being grossly pregnant, enormously full breasted, and with exaggerated vaginal labia. The sacred copulation of the god and goddess was frequently considered as being the original act of creation that had given birth to the universe, and this “heavenly marriage” was re-enacted each year, not only by the gods, but by human beings, thus ensuring the renewal of fertility. Homer referred to the time when “… Demeter, yielding to her desire, lay with Iasion in the thrice ploughed fallow land” and magically orientated acts of sexual intercourse performed on the freshly ploughed land were the culminating point of many fertility festivals; thus in Sparta, the “Corn King” copulated with the “Spring Queen” and in Orissa a similar annual event survived well into the seventeenth century.

The primitive fertility religions survived in the civilisations of the ancient and classical world. Thus the Osiris of the Egyptians, the Bacchus of the Romans and the Hermes

6

of the Greeks were all phallic gods; similarly there were sexual elements in the Mysteries of Isis and there is some reason to suppose that the Mysteries of Eleusis

may

have involved (a) a veneration of the male and female sexual organs, and (b) a ritual copulation between priest and priestess.

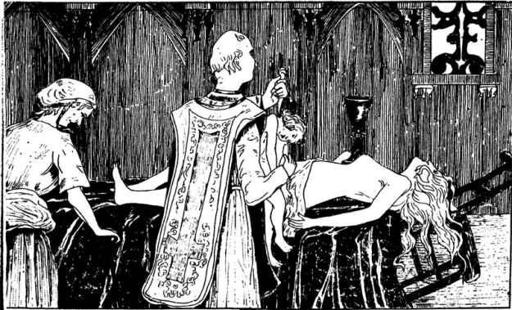

3. The Guibourg Mass—from a nineteenth-century history of sorcery.

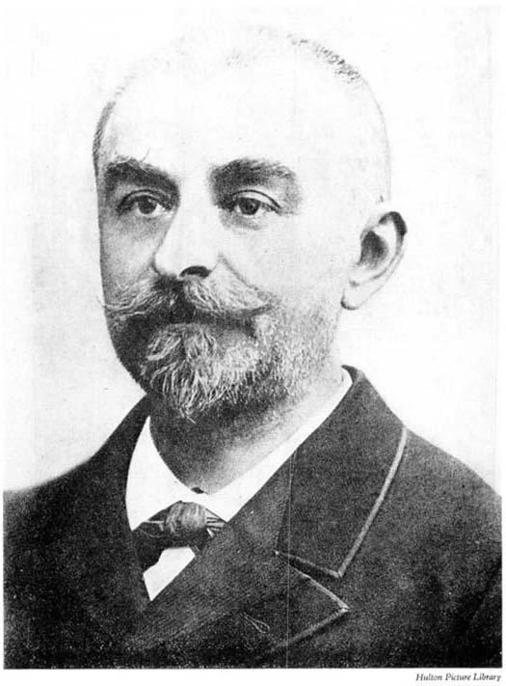

4. J. K. Huysman—his cat was subjected to magical attacks—see Appendix, “Copulating with Cleopatra”.

There was another, and darker, side to fertility religions, particularly to those in which the female principle of the earth mother was dominant. The giver of life was also the giver of death, the womb of the earth which gave birth to animal and plant had another function as the grave into which all men ultimately descended. Persephone spent half her life in the underworld and Ishtar also went down into that same shadowy half-world. It is this dark, sterile aspect of the religion of the Great Mother that may have survived in the witch-cult of the Middle Ages.

1

It is interesting to note that several authorities have claimed that in the Bengal famine of 1942 there was an actual

surplus

of food in the Indian sub-continent as a whole; the famine was caused not so much by a food production failure as by the inadequacies of the Indian railway system—there was simply no means of moving enough food from areas of food surplus to areas in which the crops had failed.

2

This conception of the gods as male and female was sometimes complicated by the existence of hermaphroditic gods who were not sexually neuter but combined within themselves male and female principles. It is significant that one of the Old Testament names of God, Elohim, is formed from a masculine singular followed by a feminine plural.

3

Professor Thom has shown, if not conclusively, at least with a very high degree of probability, that many of the megalithic structures of neolithic Britain were sophisticated lunar observatories.

4

There are grave doubts as to whether the distinction between religion and magic is a meaningful one. Some anthropologists have conceived of a “religious rite” as one that relies on the intervention of supernatural powers outside the worshipper himself and of a “magical rite” as one that relies only on the powers of the magician himself. It is doubtful whether under this definition, there has

ever

been a

purely

magical or

purely

religious ritual; even the rites of mediaeval sorcery must be considered by this definition, as being essentially religious rather than magical in nature.

5

While the pattern of a male sky deity whose function was seen as the fertilisation of the “earth-mother” was an extremely common one it was not universal. In ancient Egypt the polarity was reversed, and the sky deity was the goddess Nuit, who, thousands of years later, was to come to occupy a position of great importance in Aleister Crowley’s religion of Thelema. The reader will remember that a similar polarity reversal (between Hindu and Buddhist Tantricism) was described in the third chapter of this book.

6

The caduceus (that is to say the winged staff with intertwined serpents) of Hermes was very probably a stylised penis. Similar visual euphemisms were common in ancient iconography; thus the bodily figure of a phallic god was often used as the symbol of his penis, frequently such a god would be shown standing on a vesica-shaped boat, the latter symbolising the vagina of the goddess. Sellon stumbled on this fact and, with the over-enthusiasm that was so typical of him, claimed that just about every mythological boat was a vagina in disguise. Accordingly, he asserted that the word

Argo

, the name of the boat in which sailed Jason and his companions in the quest of the Golden Fleece, was etymologically connected with the Indian word

argha

(vagina), and that the Hebrew Ark of the Covenant, the sacred container holding the Tables of the Law, was a symbolic vagina containing a dried penis! He wrote that “there would also now appear good ground for believing that the ark of the covenant, held so sacred by the Jews, contained nothing more or less than a phallus, the ark being the type of the

argha

or Yoni” (in

Proceedings of the Anthropological Society

, Vol. I, 1865).

The Great Mother Falls on Evil Days

Thessaly was the home of Hecate, goddess of childbirth, abortion, poison and witchcraft. Originally she was probably an Asiatic goddess but the Greeks had naturalised her, and, while it can hardly be said that they had taken her into their hearts, they were certainly afraid of her, In Samothrace her worship was amalgamated with that of those extraordinary deluge-gods the Kabiri, and in Caria her worship was carried on by eunuch priests, a fact which seems to provide some link between Hecate and the Asiatic goddess Cybele, whose devotees showed their love of their Lady by self-emasculation.

By the fifth century

B.C.

Hecate had become identified with both Artemis, the chaste moon-goddess, and with “Diana the many-breasted”—yet a third Greek deity associated with the moon. The later pagans rationalised the existence of three separate moon-goddesses by arguing that the moon was the symbol of femininity and thus had three aspects; Artemis, corresponding to the young, chaste girl, Diana, symbolising the fertile mother, and Hecate, the woman who had passed the menopause, sterile, cold and dark. Nevertheless, originally Hecate was not a lunar deity, and it is probable that the identification with Artemis was made because both deities were associated with the canine world—Artemis had a pack of hounds, while the black dog was sacred to Hecate and the appearance of such a hound was popularly supposed to be a herald of her appearance—and with wild nature.

The terrifying nature of the worship of Hecate is illustrated by the following invocation of her: “Come infernal … Bombo, goddess of the broad roadways, of the crossroad, thou who goest to and fro at night, torch in hand, enemy of the day, friend and lover of darkness,

thou who dost rejoice when the bitches are howling and warm blood is spilled, thou who art walking amid the phantom and in the place of tombs, thou whose thirst is blood, thou who dost strike chill fear into mortal heart, Gorgo, Mormo, Moon of a thousand forms, cast a propitious eye upon our sacrifice.”

The connections made in this invocation between darkness, witchcraft and crossroads are of great interest, for they have survived to the present day in the darker side of the Voodoo religion of Haiti.

As I have said, Thessaly was the home of Hecate, and its women enjoyed a popular reputation for witchcraft throughout the Hellenistic world and were even supposed to have the power of “drawing down the moon” from the heavens.

1

For this reason Apuleius, when he wrote his

Metamorphoses

—a tract in favour of Isis-worship disguised as a romance—automatically sent Lucius, his marvel-seeking hero, there:

“Extremely desirous of becoming acquainted with all that is strange and wonderful I called to mind that I was in the very heart of Thessaly, celebrated by the unanimous consent of the whole wide world as the land where the spells and incantations of magic are, so to speak indigenous …”

The cult of Hecate and Greek beliefs about witchcraft spread to Rome where, perhaps, certain dark cults, remnants of Etruscan magic, already enjoyed a shadowy existence. Thus Horace described an incantation at which a black lamb was torn to pieces, while still living, as a sacrifice to Hecate, and belief in Black Magic was so widespread that when Antinous, the favourite of the Emperor Hadrian, was accidentally drowned in the Nile it was popularly rumoured that he had been sacrificed as part of a magic spell designed to lengthen the Emperor’s life-span.