Shadow Divers (42 page)

Kohler’s first appointment was with Hans-Georg Brandt, First Officer Siegfried Brandt’s younger brother. Now seventy-one years old and a retired auditor, Hans-Georg waited nervously at his son’s home for Kohler’s arrival, his son and grandchildren also eager to see the face of one of the divers who had risked his life to find Siggi. Kohler knocked. Hans-Georg, dressed for the occasion in fine tan slacks, a brown cardigan sweater, and a tie, opened the door. For a moment, the men just looked each other over. Then Hans-Georg stepped forward, took Kohler’s hand, and spoke in halting English.

“I am deeply touched that you have come. And I am so sorry for what happened to the brave divers who lost their lives on the U-boat. Welcome.”

For six hours, Hans-Georg remembered his brother Siggi, a brother he loved today as much as he had at thirteen when Siggi showed him the secrets of his U-boat and allowed him to look through its periscope out into the world. The conversation was emotional and painful for Hans-Georg at times. At the day’s end, Hans-Georg thanked Kohler again and helped him find his coat.

“I brought you something,” Kohler said. He reached into his briefcase. A moment later he produced a metal schematic he had recently recovered from

U-869

’s electric motor room.

“You were probably in this room when you visited your brother,” Kohler said.

Hans-Georg took the schematic and stared at the metal, at its writing and rust. For several minutes, he could not break his gaze from the artifact. Finally, he began tracing his fingers along its edges and over its crusty surface.

“I can’t believe it,” he said. “I will save this forever.”

The next morning, Kohler and Bowling drove several miles outside Hamburg to meet with a sixty-year-old surgeon. The man, thin, tall, and handsome, welcomed the Americans into his home. He introduced himself as Jürgen Neuerburg, the son of

U-869

’s commander, Helmuth Neuerburg.

Jürgen could produce no memories of his father, as he’d been just three years old when

U-869

was lost. But he remembered well his mother’s stories, and the fondness and love with which she’d told them. For hours, while his wife listened closely, he shared these stories with Kohler, showing dozens of photographs and diary entries in between.

“Since I was a child, I believed my father had been lost off Gibraltar,” Jürgen said. “When I learned that divers had found the boat off the coast of New Jersey, I was very surprised. But in the end it did not change how I felt. I suspect it might have shocked my mother, such a revelation after so many years of believing the official version of events. For this reason, I’m happy she never found out about it. She loved him dearly. She never remarried.”

Kohler asked Jürgen if his father had siblings. Indeed, his father had an older brother, Friedhelm. Kohler asked if Jürgen might provide a telephone number for Friedhelm. Jürgen gave him an old number.

“I don’t even know if he’s still alive,” Jürgen said. “Sadly, we have fallen out of touch.”

Jürgen and his wife thanked Kohler for his efforts and asked him to thank Chatterton when he returned to New Jersey. That night at the hotel, Kohler and Bowling dialed the number. An elderly woman answered. Bowling introduced herself as the sister of one of

U-869

’s crewmen. The woman said she would be happy to bring her husband to the phone.

For the next hour, eighty-six-year-old Friedhelm Neuerburg remembered his brother, Helmuth.

“When I close my eyes and picture my brother today,” Friedhelm said, “I see him doing his duty. I think he had a premonition that he wasn’t coming back. He did his duty.”

In the morning, Kohler and Bowling drove from Hamburg to Berlin. That evening, Kohler met with forty-year-old Dr. Axel Niestlé, the head of a private engineering firm that works on waste-disposal projects. Niestlé’s doctorate, earned in water-resources science, was based largely on work he did in North Africa. In his spare time, as a sort of hobby, Niestlé had made himself the world’s foremost authority on the reassessment of U-boat losses. It was Niestlé who, in 1994, had thought to look at the intercepted radio messages between

U-869

and U-boat Control, an idea that had occurred to no one else in the world for history’s certainty that

U-869

lay sunk off Gibraltar. He’d communicated his findings in a written report to Robert Coppock at the British Ministry of Defence, who’d then relayed the information to Chatterton and Kohler via letter. During their meeting, Kohler marveled not just at the depth of Niestlé’s knowledge but at his passion for the subject. He asked Niestlé why he wasn’t teaching at a university.

“U-boats are my avocation,” he said. “Perhaps it would be boring if I were to earn money from it. It’s the detective’s way of treating these matters that moves me. Once you find out history is wrong, once you start investigating it and, with some luck, correcting it, that is satisfaction enough.”

The next day, Kohler and Bowling took the Berlin subway to the quaint home of an elderly lady. On a mantelpiece in the living room’s center were framed photos of her children and one of a young, handsome man from World War II who seemed to look forward into the ages. The woman introduced herself as Gisela Engelmann. The man in the photo, she said, was her fiancé, Franz Nedel, one of

U-869

’s torpedomen.

For hours, Engelmann told Kohler about tearing the eyes out of Hitler’s picture, about climbing the gas lamp and displaying Hitler’s photo for all Berlin to see, about the going-away party at which Franz and his fellow crewmen broke down in tears, about how she knows more than ever that there is only one true love in a person’s life, and for her that love was Franz.

“My two husbands knew about Franz, of course,” she said. “When I would speak of Franz to my children, they would roll their eyes and say, ‘Mother, you’ve told us this story a hundred and fifty times already.’”

As with the Brandts, Engelmann was left to wonder about her loved one’s fate long after the war’s end. It was not until October 1947 that she received official word that

U-869

had been declared a total loss.

“I missed him every day of my life,” she told Kohler. “I have his photograph in my bedroom, and I have looked at it every day, through two marriages and four children, since I waved good-bye to him.”

Kohler had one more appointment before flying back to New Jersey. He and Bowling flew to Munich, rented a car, and drove west through miles of breathtaking, snow-covered rural landscape. Kohler exited at the small town of Memmingen and followed his directions. A few minutes later, he found himself in the city center, a place of winding streets, centuries-old buildings, and church spires that reached into the heavens. Memmingen, he thought, was a painting, the storybook Germany that Mr. Segal, the circus strong man, had described to his father.

Kohler maneuvered down narrow side streets until he arrived at one of the town’s most ancient homes. He rang the doorbell. A minute later, a handsome and dignified eighty-year-old gentleman opened the door. Dressed in a blue suit and red tie, his cotton-white hair combed perfectly, he looked as if he had been expecting his visitor for years.

“I am Herbert Guschewski,” the man said. “I was the radioman aboard

U-869.

Please welcome to my home.”

In his living room, surrounded by his family, Guschewski told Kohler the story of how he had survived

U-869.

On a warm November morning in 1944, just days before

U-869

was to leave for war, Guschewski found himself feeling ill. When he stepped outside for fresh air, he became dizzy and collapsed, unconscious. Onlookers rushed him to the hospital, where he remained in a coma with a high fever for three days. When he came to, the doctors told him he had contracted pneumonia and pleurisy. Though

U-869

was to depart in hours, he would be forced to remain in intensive care. He was also told he had visitors.

His hospital door opened. Standing before him, holding chocolate, cookies, and flowers, was Commander Neuerburg. Behind him were First Officer Brandt and Chief Engineer Kessler. And behind them were many of the U-boat’s crew. Neuerburg approached Guschewski. He wiped the radioman’s forehead and stroked his arm.

“You’ll be all right, my friend,” Neuerburg said.

Brandt stepped forward and took Guschewski’s hand.

“Get well, friend,” he said, smiling the same smile Guschewski had seen after he’d told Brandt his jokes. “You will pull through.”

Kessler came forward, as did Horenburg and the other radiomen. Many had tears in their eyes. They wished Guschewski well.

“It finally came time to say good-bye,” Guschewski told Kohler. “I had the feeling that we would not see each other again. When I looked into the eyes of some of my comrades, I could see they thought the same.”

Like everyone else, Guschewski had believed that

U-869

had been sunk off Gibraltar. When he’d got word that divers had found the U-boat off New Jersey, he’d contacted

Spiegel.

It was through

Spiegel

that Kohler had come to know of Guschewski.

Kohler stayed for two days. Guschewski spoke for hours about Neuerburg, Brandt, Kessler, and the other men he knew from

U-869.

He recounted the bombing of the barracks in Stettin, singing along to Neuerburg’s guitar playing, inadvertently dialing in Radio Calais, Fritz Dagg’s ham theft, his friendship with Horenburg. He spoke at length about Brandt’s kindness and ready laugh and his willingness, even at age twenty-two, to bear the fear and trembling of others. He told Kohler that he missed his friends.

“It is horrible for me to see the way the boat lies broken in the ocean,” Guschewski said. “For more than fifty years I remembered it as new and strong, and I was part of it. Now I look at the film and pictures and see the remains of my comrades. . . . It is very difficult and sad for me to think of it this way.

“I believe in God and an afterlife. It would be wonderful to be reunited with my friends, to see them again, and to see them continue in peace, not in war, not in a time when so many young lives were lost for no reason. I would like to see them like that.”

After a second day of conversation, Kohler and Guschewski rose and shook hands. Kohler’s flight to New Jersey departed in just a few hours, and Guschewski, an esteemed town councillor, had a meeting that evening. Each had more questions for the other. Each promised another visit so that the questions would not go unanswered for long.

As Kohler reached for his coat, Guschewski made a request.

“Might it be possible to send me something from the boat?” Guschewski asked. “Anything would do. Anything I could touch.”

“I would be happy to,” Kohler said. “I will send you something the moment I return home.” He already knew what he would send—a five-by-six-inch plaque from the emergency life raft canister explaining that item’s operation.

“That would mean very much to me,” Guschewski said. He waved good-bye to Kohler and closed the door.

As Kohler walked toward his car, he felt the bands of his obligation loosen. No one should lie anonymous at the bottom of the ocean. A person’s family needs to know where their loved one lies.

It had grown colder outside since Kohler had arrived. He reached for his car keys. Guschewski pushed open his front door and walked into the winter. He was not wearing a coat. He moved toward Kohler and put his arms around the diver.

“Thank you for caring,” Guschewski said. “Thank you for coming here.”

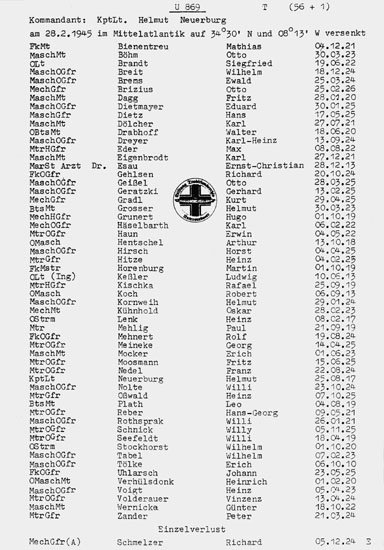

U-BOAT ARCHIVE, CUXHAVEN, GERMANY

U-869

crew list.

JOHN CHATTERTON

Spare-parts box recovered by Chatterton from the electric motor room. Note the identifying number in the upper left corner of the box’s tag—the number that finally identified the wreck and solved one of the last mysteries of World War II.

RICHIE KOHLER

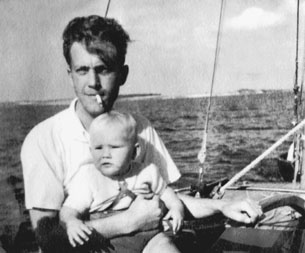

Martin Horenburg.

RICHIE KOHLER

Martin Horenburg aboard

U-869

.

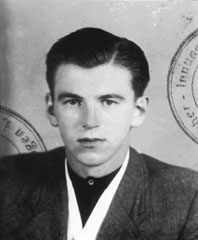

HERBERT GUSCHEWSKI

Herbert Guschewski, radioman,

U-869

.

HERBERT GUSCHEWSKI

Neuerburg (

far right

) saluting the ship’s ensign after commissioning the boat on January 26, 1944.

JüRGEN NEUERBURG

Helmuth Neuerburg, commander,

U-869.

JüRGEN NEUERBURG

Neuerburg used leaves to take his two-year-old son, Jürgen, for sailboat rides and to bounce his infant daughter, Jutta, on his knee. Just before

U-869

’s commissioning, he spoke to his brother, Friedhelm. This time, he mentioned nothing of the Nazis. He simply looked Friedhelm in the eye and said, “I’m not coming back.”

RICHIE KOHLER

Siegfried Brandt, first officer,

U-869.

RICHIE KOHLER

When Brandt’s brother Hans-Georg asked their mother why she wept at this picture of Siegfried sleeping aboard

U-869,

she told him that it was the way Siggi was sitting—it reminded her of a child, a baby, and even though Siggi was a proud warrior, she could still see her little boy in that photograph.

GISELA ENGELMANN

Franz Nedel, torpedoman,

U-869.

GISELA ENGELMANN

Gisela Engelmann, fiancée of Franz Nedel.

RICHIE KOHLER