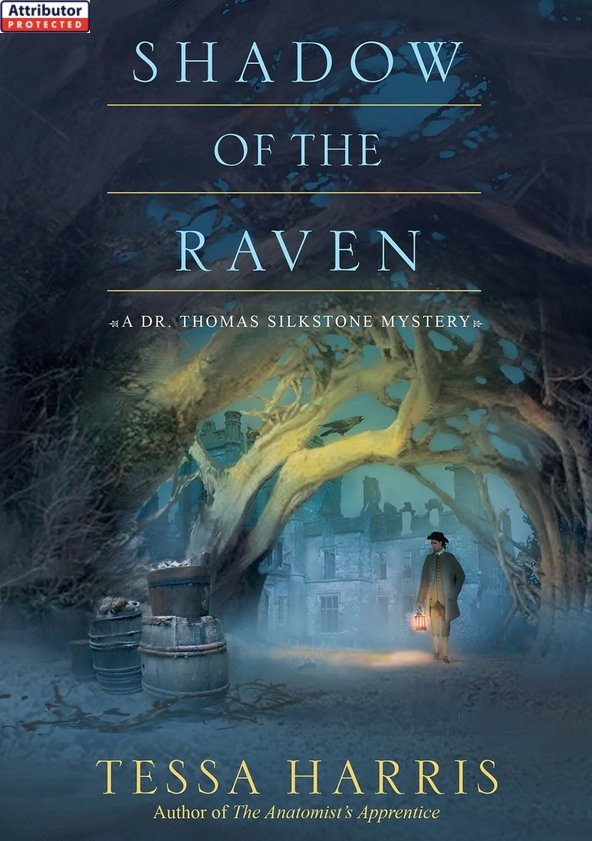

Shadow of the Raven

Read Shadow of the Raven Online

Authors: Tessa Harris

Outstanding praise for Tessa Harris and her Dr. Thomas Silkstone Mysteries!

Â

The Lazarus Curse

Â

“Stellar . . . Harris's prose and characterizations have

only become more assured.”

âPublishers Weekly

(starred review)

only become more assured.”

âPublishers Weekly

(starred review)

Â

The Devil's Breath

Â

“Excellent . . . Both literally and figuratively atmospheric,

this will appeal to fans of Imogen Robertson's

series during the same period.”

âPublishers Weekly

(starred review)

this will appeal to fans of Imogen Robertson's

series during the same period.”

âPublishers Weekly

(starred review)

Â

The Dead Shall Not Rest

Â

“Highly recommended.”

âHistorical Novel Reviews

âHistorical Novel Reviews

Â

“Populated with real historical characters and admirably

researched, Harris's novel features a complex and engrossing

plot. A touch of romance makes this sophomore outing

even more enticing. Savvy readers will also recall

Hilary Mantel's

The Giant, O'Brien

.”

âLibrary Journal

researched, Harris's novel features a complex and engrossing

plot. A touch of romance makes this sophomore outing

even more enticing. Savvy readers will also recall

Hilary Mantel's

The Giant, O'Brien

.”

âLibrary Journal

Â

The Anatomist's Apprentice

Â

“Tessa Harris takes us on a fascinating journey into the

shadowy world of anatomist Thomas Silkstone, a place where

death holds no mystery and all things are revealed.”

âVictoria Thompson, author of

Murder on Sisters' Row

shadowy world of anatomist Thomas Silkstone, a place where

death holds no mystery and all things are revealed.”

âVictoria Thompson, author of

Murder on Sisters' Row

Books by Tessa Harris

THE ANATOMIST'S APPRENTICE

THE DEAD SHALL NOT REST

THE DEVIL'S BREATH

THE LAZARUS CURSE

SHADOW OF THE RAVEN

THE DEAD SHALL NOT REST

THE DEVIL'S BREATH

THE LAZARUS CURSE

SHADOW OF THE RAVEN

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

SHADOW OF THE RAVEN

A DR. THOMAS SILKSTONE MYSTERY

TESSA HARRIS

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Outstanding praise for Tessa Harris and her Dr. Thomas Silkstone Mysteries!

Books by Tessa Harris

Title Page

Dedication

Author's Notes and Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Postscript

Glossary

Copyright Page

Books by Tessa Harris

Title Page

Dedication

Author's Notes and Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Postscript

Glossary

Copyright Page

To Katie and Gabriella, with love

Author's Notes and Acknowledgments

P

icture a typical English landscape and it will probably look something like this: gently rolling green hills divided into neat fields, lined with high hedgerows and dotted with deciduous woodland.

icture a typical English landscape and it will probably look something like this: gently rolling green hills divided into neat fields, lined with high hedgerows and dotted with deciduous woodland.

But this “green and pleasant land,” as the poet William Blake so famously called it, is not natural. It is the product of man, and more precisely of landowners. Over the centuries the English countryside has been both hunted and fought over, foraged and farmed, burned and felled, divided and developed, to produce the landscape we know today: a crowded network of cities, towns, and villages with patches of agricultural land in between. And in a very few places, tracts of land are allowed to be natural, even though they still need managing. These are England's commons and common woodlands, where the public is free to roam. Some of these areas fall within the boundaries of national parks or are owned by the National Trust, a conservation charity. Others give access and rights of way, and they form the backdrop to this, the fifth novel in the Dr. Thomas Silkstone Mystery series.

As usual I have taken my inspiration from a true story. Between 1604 and 1905 almost eleven thousand square miles of land were “enclosed” by Acts of Parliament in the United Kingdom. These acts became more numerous as the effects of the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries began to take hold. Land once farmed and enjoyed by the community was fenced off to produce higher yields, and rents were increased. As a result, many peasants were forced away from their homes to seek work in towns and cities, causing huge disruption, dispossession, and discontent, which, in turn, culminated in major riots in the 1830s.

Otmoor is an area of land that lies to the north of Oxford, and my inspiration came from the resistance of its inhabitants to enclose it. Although the moorland was eventually enclosed, it took almost forty-five years, several attempts at sabotage, and many violent protests before the estate's owner, the Duke of Marlborough, could achieve his goal. The people of Otmoor put up a courageous fight, often landing in jail and even risking execution, to preserve their rights, which, they seemed to have believed in all sincerity, were given to them by a mythical lady. Some even said the Virgin Mary had originally bestowed the land upon them. In their struggle they had much sympathy. The extraordinary account of their release from custody by an Oxford mob is well documented, as are numerous gatherings around the area that saw the deliberate destruction of scores of miles of fencing. In a handful of cases the military was called upon to restore order. A permanent police presence had to be maintained to keep the peace. The unrest continued intermittently for many years, eventually leading to the riots of 1829â1830. Finally, two years later, opposition to enclosure seemed to have melted away and the landowners in the area had their way.

In my research I have been helped and encouraged by the following people: historic firearms expert Geoff Walker, Ian Macintosh with his knowledge of fulling mills, and woodsman Jon Roberts of the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum. As ever, my thanks go to my editor, John Scognamiglio; my agent, Melissa Jeglinski; John and Alicia Makin, Dr. Kate Dyerson, Katy Eachus, John and Mary Washington-Smith, and Liz Fisher. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my husband, Simon, my children, Charlie and Sophie, and my parents, Patsy and Geoffrey.

Thus, with the poor, scared freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law's enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law's enclosure came

And dreams of plunder in such rebel schemes

Have found too truly that they were but dreams.

Â

â“The Mores,” John Clare (1793â1864)

Chapter 1

Oxfordshire, England

April in the Year of Our Lord 1784

April in the Year of Our Lord 1784

Â

W

as that blood on his stockings? For the second time, or maybe the third, the gentleman had stumbled on the steep slope. Catching his buckled shoe on a slippery shard of flint, he had lurched forward.

as that blood on his stockings? For the second time, or maybe the third, the gentleman had stumbled on the steep slope. Catching his buckled shoe on a slippery shard of flint, he had lurched forward.

His young assistant's head darted 'round in shock as his master clipped his shoulder. “S-s-sir!” he stammered.

Cursing under his breath, the older man righted himself, tugging at his fustian coat. As he did so there was a clatter. An object fell from his pocket onto the stony ground below. Having a good idea what it might be, he peered down. And now, as he did so, he noticed that his worsted stockings, although thankfully not torn, were spattered dark red. A closer inspection, however, confirmed the substance was only loamy mud. What concerned him more was the fact that a few inches from his feet he spied the pistol. Mercifully, although fully cocked, it had not fired. Bending low to retrieve it, he secreted the weapon in his pocket once more and allowed a shallow sigh of relief to escape his lips. He felt safer with it about his person. It would be a deterrent, if one were needed, against any undesirables they might encounter. A quick glance up ahead reassured him that his assistant had not seen.

“Infernal stones,” cursed the gentleman out loud, making sure his complaint was heard by Charlton, his chainman. The freckle-faced young man turned 'round and nodded his red head in agreement.

Jeffrey Turgoose, master surveyor and cartographer, a man held in high regard by the rest of his profession, should have worn stout boots more suited to a woodland trail, although, admittedly, he had not anticipated having to make his way through the forest on foot. A series of unfortunate events had, however, necessitated it.

First and foremost, his employment, thus far spent in the service of Sir Montagu Malthus, the new caretaker of the Boughton Estate and lawyer and guardian to the late sixth Earl Crick, had been fraught with difficulties. Every time he had set up his theodolite in the estate village of Brandwick, he had been taunted by barefoot urchins or impudent fellows intent on disrupting his mission. There had been threats, too. In his pocket he carried the note that had been slipped under his door the other night.

Beware of Raven's Wood,

it warned him. Heaven forbid that Charlton should see that! The boy would run all the way back to Oxford. Turgoose harrumphed at the very thought of it. No, it would take more than ignorant peasants and a badly scrawled warning from a lower sort to deter him. Nonetheless, such unpleasantness did, of course, rankle. He could not pretend otherwise, and it added to a certain miasma that seemed to hang low over Brandwick and its surrounds.

Beware of Raven's Wood,

it warned him. Heaven forbid that Charlton should see that! The boy would run all the way back to Oxford. Turgoose harrumphed at the very thought of it. No, it would take more than ignorant peasants and a badly scrawled warning from a lower sort to deter him. Nonetheless, such unpleasantness did, of course, rankle. He could not pretend otherwise, and it added to a certain miasma that seemed to hang low over Brandwick and its surrounds.

From what he had gleaned, there seemed to have been great ructions on the estate. Apparently, the death of Lord Edward Crick, swiftly followed by that of his brother-in-law, Captain Michael Farrell, had been most inopportune. They meant that the latter's widow, Lady Lydia Farrell, had inherited Boughton. It was thought she was childless, but the reemergence of her long-lost young son and heir, thanks in no small part to an American anatomist by the name of Dr. Thomas Silkstone, had put a fly in the proverbial ointment. What's more, it appeared that such upheavals had taken their toll on the poor woman and sent her quite insane. She was now safely ensconced in a madhouse, and Sir Montagu had installed a steward to take charge of the quotidian running of the estate.

If that were not enough, Jeffrey Turgoose was encountering his own problems. First the cart that carried himself and his equipment became bogged down and stuck fast in the yielding ground leading up to the wood. For the past few months now man and beast had left their imprint on the sodden earth. Now the cartway was so beaten down by wheels and hooves it had become impassable. Not wishing to abandon his plans, the surveyor had continued with just one blasted mount that went by the name of a horse, although in reality it was just as stubborn as a mule. His assistant, Mr. James Charlton, had been forced to dismount and walk in order to lay the burden of all the paraphernalia of their profession on his own horse. Peeping out of one pannier were bundles of markers and a circumferentor, while the other was packed with measuring chains. A tripod was strapped to the saddle, along with some measuring poles, making the poor horse appear as if she had been run through with a picador's lances.

Such unforeseen irritations had put the surveyor in a very sour humor. Was his mission not onerous enough? He was not accustomed to exercising his profession under threat from local ruffians, but such had been the villagers' reaction to their presence, he had been compelled to take precautionary measures. The ignorant peasants were harboring the notion that the common land had been bestowed upon them by some mythical woman. “The Lady of Brandwick” they called her, and they all knew the legend. While still at the breast they were taught how, in the days before Bastard William invaded, a lady had ridden a circuit of the area from the edge of the woods to where the oxen could ford the river. In her hand she held a flaming brand and by her favor she gave the land to the villagers. That was how the parish came to be known as Brandwick, and that was how they came by their ancient rights. Or so they thought.

In fact, Boughton's steward, the Right Honorable Nicholas Lupton, appointed by Sir Montagu as the new custodian of the estate, had indicated that he felt his own position was being compromised by such innate insubordination. The Chiltern charcoal burners, turners, and pit sawyers who labored in the forest all day were not known to be militant men, Lupton had told him, but since their livelihoods were under threat, since their cherished rights were in peril, there was no telling what they might do. Pointing out that there had been riots in other parts of the country where landowners had endeavored to enact similar measures, the steward had persuaded Turgoose to have a greater care for his own safety and that of his assistant. He had been persuaded by Lupton's recommendation of a guard and guide, Seth Talland, an occasional prizefighter and an uncouth sort. The man seemed competent enough, and, as it turned out, he was most thankful for his presence. Apart from the threat of lurking highwaymen and footpads, there were gin traps, too, set about the woodland floor to deter poachers. There were still a few men in Brandwick who'd suffered a leg snapped in two by the iron jaws of such a brutal device. They never poached, or walked without a limp, again.

Lupton had told him there were upward of three hundred acres of woodland, and measuring the boundaries alone would take three days at a conservative estimate. He'd heard that in America they'd surveyed seventeen thousand acres in just over a sennight in Virginia. But they had not measured angles to the nearest degree, and their distances were to the nearest pole. Such slipshod work would not pass muster with Jeffrey Turgoose.

“W-would you r-rest, s-sir?” Charlton's speech was always labored, and often the most frequently used words seemed to cause him anguish, yet he looked even more concerned than usual.

“A moment,” Turgoose replied, turning his back to the slope and looking down into the valley at Brandwick. A fading sun hung in a patchy sky, offering a less-than-perfect light. He was glad of his decision to bring his trusty old circumferentor instead of his usual theodolite. Akin to a large compass, it worked on the principle of measuring bearings. It would be particularly advantageous, he felt, in such a heavily forested area, where a direct line of sight could not be maintained between two survey stations, even though he could see the tower of St. Swithin's Church clearly enough. He shook his head as he took in the view. He'd even heard of some of his colleagues having to survey land under cover of darkness, like fly-by-night poachers, such was the strength of feeling against enclosure.

Of course, Turgoose, too, had expected some suspicion and resentment. He was accustomed to that from those who had most to fear from enclosure, cottagers, mainly, and those who faced losing their livelihoods. A free rabbit for the pot or kindling for the fire had been the mainstay of many a paltry existence over the centuries. But times were changing. Land was a precious commodity, best managed by those who knew how to make it pay. So he and his assistant had been commissioned to plant themselves on Brandwick Common like unwelcome thistles, to record the mills and monuments, the wetlands and ponds, and the bridleways and tracks and paths made by feet that had trodden them freely since time immemorial.

To those ignorant peasants, he and his assistant may as well have been alchemists, with their strange equipment in tow. There was, of course, an analogy. Alchemists turned metal into gold, while he and his cohort were turning land into potential profit. That is what his client, Sir Montagu, wanted to do on behalf of Lord Richard Crick, Boughton's six-year-old master.

Despite the hostility from the villagers, the surveyors had managed to do a good job thus far. The weather, although on the chilly side, had been fair, the sky clear, and their observations and measurements easily recorded. After the common land, they had turned their attention to the village dwellings, the market cross, and the church, all lying within the boundaries of the Boughton Estate. Precision and order could be imposed on this chaotic fretwork of man's own making using that most noble of shapes, the triangle. Trigonometry was the answer to all humankind's conundrums; at least that is what Jeffrey Turgoose had told Charlton and anyone else who would listen. After all, was it not Euclid, the father of geometry, who said that the laws of nature were but the mathematical thoughts of God? To that end, he had convinced himself that he was doing the Almighty's work, and this confounded wood was his final task.

Up ahead, Talland, his scalp as bald as a bone, looked 'round to see what had happened to his charges. Set square as a thicknecked dog, he carried a club for protection, and a small sickle hung from his waist.

“All well, sirs?” he called back in a coarse whisper. Thankfully he was a man of few words, thought the surveyor.

“Well enough,” replied Turgoose. He gave Charlton a knowing look and proceeded to delve into his frock coat pocket. He checked that the pistol was still there. The youth did not suspect. Such knowledge would send him into paroxysms of fear. Instead Turgoose brought out a hip flask and took a swig.

Talland emerged from the lengthening shadows a moment later.

“I'll make safe our way, sirs,” he told them. “I 'eard sounds from up yonder.”

Turgoose nodded, then turned his back and gave a derisory snort. “I'll wager you have heard sounds, man,” he said to himself as much as to Charlton. “We are on the edge of a wood. There are foxes, squirrels, and all manner of creatures, not to mention the wretched charcoal burners and sawyers.” He shrugged, took another swig, then plugged the flask once more.

The old mare shifted as she stood and began to fidget under the weight of her burden. Charlton frowned at his master.

“Wh-what if there's s-someone up there, s-sir?” he asked. Turgoose noted that when his assistant was anxious, the register of his voice went even higher than usual. Dropping the flask into his pocket, the surveyor shook his head.

“Then Talland will deal with them,” he reassured the chainman, even though he did not feel entirely secure himself. This was no way to carry on: three men, and a mare that should've been boiled down for glue a long time ago. His was a most burdensome and precise task, so why had he been made to feel like a cutpurse or a scoundrel going about his business?

As they breasted a small ridge, Talland, who had momentarily been lost from sight behind a screen of spiky gorse, came into view once more. The prizefighter had made it to the trees and was entering the wood through an avenue of tight-packed hawthorns. If need be, he would clear a path for them to follow a few paces behind.

The beeches were still naked after one of the longest winters in memory. Crows' nests clotted their bare branches and russet leaves still patterned the woodland carpet. Crunching over cast-off acorn caps and husks of beech mast, the small party proceeded at a tolerable rate. They wove through green-slimed trunks and past thickets as tangled as an old man's beard. By now they had left behind the birdsong and the caw of the crows, although the odd pheasant would let loose a throaty call. All the while they were heading deeper and deeper into the woods.

Turgoose's plan was to determine the apex of the hill in the wood and then take measurements using the church tower as a fixed point. The task would have presented its own challenges had he been operating in clear conditions, but with the fading light the execution of such an undertaking would rightly be considered sheer folly by many of his fellow surveyors.

Moments later the party found themselves progressing along the narrow avenue of hawthorns. Underfoot it remained muddy, but Talland had found a serviceable path that, judging by the lack of vegetation, seemed to be in regular use. They were forced to travel in single file, with Charlton leading the horse first. They had journeyed perhaps a mile into the woods when the mare's ears pricked and she came to a sudden halt. The young man tugged at her leading rein.

“Come on, old girl,” he said firmly. Instead of obeying the command, however, she began to backstep, forcing Turgoose to retreat.

“What goes on?” he called from the rear.

“She's afraid, sir. . . . S-something tr-troubles her.”

Turgoose tutted and, seeing a row of dried-out stalks at his side, he broke one off near its root and thwacked the mare's hindquarters.

“Get on with you,” he cried.

The shock had the desired effect and the horse moved at once. It was Charlton who was now reluctant to budge.

“Well, man?” asked Turgoose impatiently. “What is it now?” Passing the horse, he drew up alongside his nervous assistant to find him squinting into the distance.

Other books

Secrets From the Past by Barbara Taylor Bradford

The End by Charlie Higson

Virgin Star by Jennifer Horsman

Test Pilot's Daughter II: Dead Reckoning by Ward, Steve

Midnight Lamp by Gwyneth Jones

A Very Bad Billionaire (BWWM Contemporary Romance Novel) by Vivian Ward

Run (Book 2): The Crossing by Restucci, Rich

No Holds Barred by Paris Brandon

Dying to Run by Cami Checketts