Shadow River (24 page)

Authors: Ralph Cotton

The ground shuddered underfoot. He swayed slightly in his saddle, but then he caught himself and let the tremor pass without so much as slowing down for it. The dun nickered and blew out a breath but stayed steady and straight.

That's just how it is here

.

You never know what to expect,

he told himself.

So expect anything. . . .

In seconds the desert hill country shivered and settled with a familiar hard thump. Sam nudged the dun forward and rode away, the white barb beside him, the string of horses close behind.

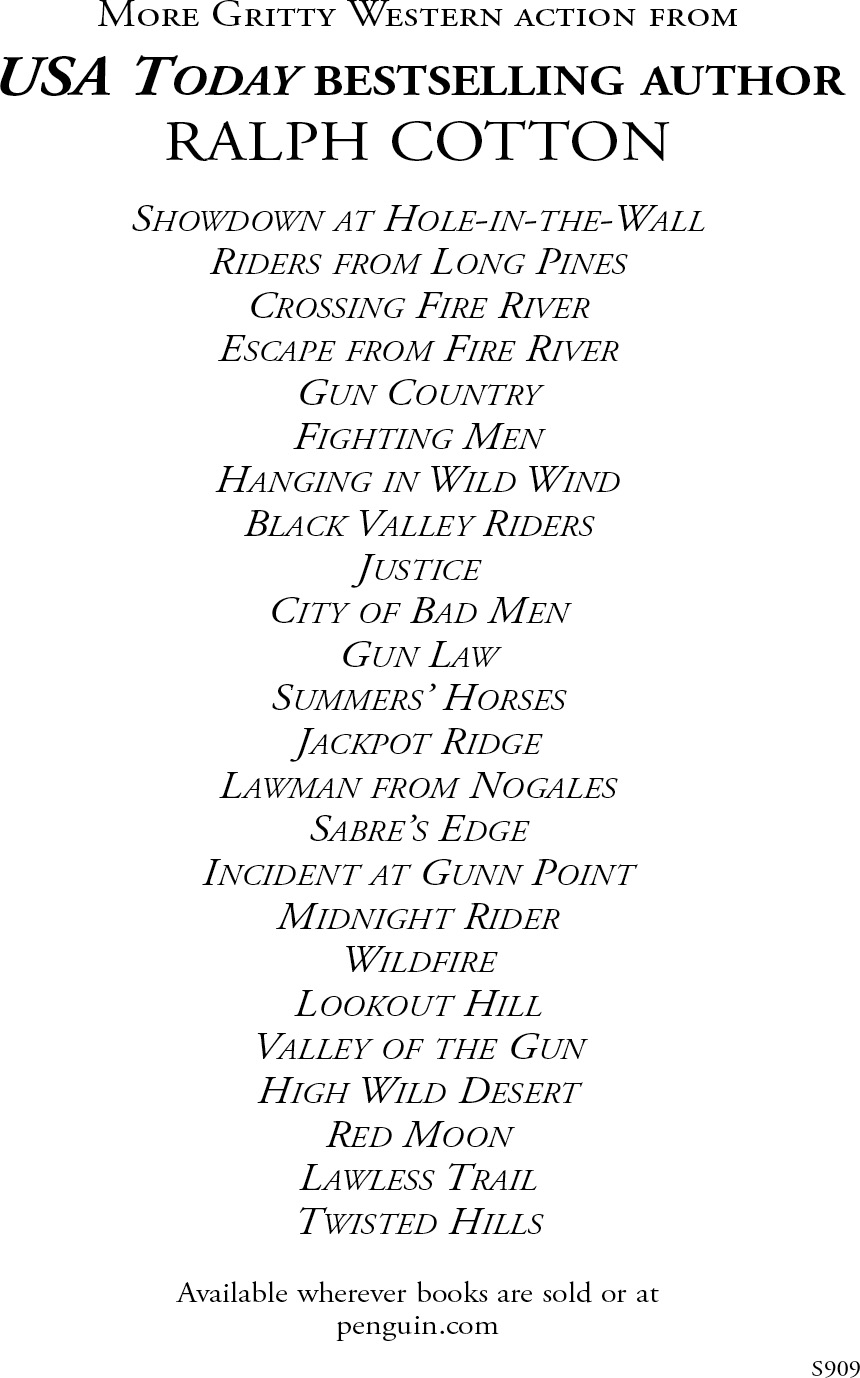

Horse trader Will Summers is back! Don't miss a page of action from America's most exciting Western author, Ralph Cotton.

DARK HORSES

Available from Signet in June 2014.

Dark Horses, the Mexican hill country, Old Mexico

The horse trader Will Summers stood with his rain slicker buttoned all the way up to his chin, his wet black Stetson pulled low on his forehead. His boots were muddy and soaked through his socks. His wet, gloved hand wrapped around the stock of his equally wet Winchester rifle. Behind him stood his dapple gray and a string of four bay fillies. The animals held their heads bowed against the rain.

Summers read a bullet-riddled sign he'd picked up out of the mud. He slung it free of water and mud and read it again as if he might have missed something.

Bienvenido a Caballos Oscuros . . . ,

he said silently to himself.

“Welcome to Dark Horses,” he translated beneath the muffling sound of pouring rain.

But how far?

he asked himself, looking all around. The rain raced slantwise on a hard wind. Thunder grumbled behind streaks of distant lightning. Night was falling fast under the boiling gray sky. The horse trader frowned to himself and looked up and down the slick hillside trail.

To his right he looked along a boulder-clad hillside to where the long rocky upper edge of an ancient caldera swept down and encircled the wide valley below. The lay of the rugged land revealed where thousands of years ago the lower valley had been the open top of a boiling volcano. Over time, as the belly of the earth cooled, the thin standing pipe walls of the volcano had weathered and aged and toppled inward and filled that once smoldering chasm. All of this before man's footprints had ventured onto this rugged terrain.

Behind the fallen honeycombed lava walls, over those same millennia past, dirt and seed of all varieties had steadily blown in and sculpted a yawning black abyss into a rocky green valleyâa valley currently shrouded beneath the wind-driven rain.

On the valley floor, snaking into sight from the north, Summers recognized Blue RiverâEl RÃo Azul. The river's muddy water had swollen out of its banks and barreled swiftly in and around bluffs and lower cliffs and hill lines like an unspooling ribbon of silk. As he studied the hillside and the valley below him, a large chunk of rock, gravelly mud and an unearthed boulder broke loose before his eyes and bounced and slid and rumbled down to the valley floor.

Whoa. . . .

Summers turned his eyes back along the wet hillside above him, knowing the same thing could happen up there at any second. It didn't matter how much farther it was to Dark Horses; he had to get himself and the horses somewhere out of this stormâ

somewhere safer than here,

he told himself. Blowing rain hammered his hat brim, his boots, his slicker and the glassy, pool-streaked ground around him. Lightning twisted and curled. Behind it a clap of thunder exploded like cannon fire.

“Welcome to Dark Horses,” he repeated, saying it this time to the dapple gray who had pressed its muzzle against Summers' arm.

The gray chuffed, as if rejecting both Summers' invitation and his wry attempt at humor. Behind the gray the four black-point bay fillies milled at the sound of thunder. Then they settled and huddled together behind the gray. The fillies were bound for the breeding barn of an American rancher by the name of Ansil Swann.

Dry, the fillies' coats shone a lustrous winter wheat red, highlighted against black forelegs, mane and tails. But the animals hadn't been dry all day. Summers intended to rub them down and let them finish drying overnight in a warm livery barn. Get them grained and rested before the new owner arrived in Dark Horses to take delivery. But so much for his plan, he thought, realizing the storm would no doubt pin him down out here for the night.

“Let's find you and these girls some shelter,” he murmured to the gray. The gray slung water from its soaked mane.

But where?

Summers looked around more as he gathered his reins and the lead rope to the fillies. Swinging himself up across his wet saddle, he reminded himself that he'd seen no sign of a cliff shelter anywhere along the ten or so miles of high trail behind him.

“We'll find something,” he murmured, nudging the gray forward. The fillies trudged along single file behind him, their images flickering on and off in streaks of lightning.

He rode on.

For over an hour and a half he led his wet, miserable procession through the storm along the darkened hillside trail. Twice he heard the rumble of rock slides through the pounding rain ahead of him, and twice he'd had to lead the horses off the blocked trail around piles of stone wreckage. But what else could he do? he reasoned. Stopping on this loose, deluged hillside was out of the question.

Find shelter or keep moving

, he told himself. There was no third choice in the matter.

Beneath his wet saddle the gray grumbled and nickered under its breath at each heavy clap of thunder. Yet the animal made no effort to balk or pull up shy even with its reins lying loose in Summers' hand. Following the gray's lead, the four fillies stayed calm. For that Summers was grateful.

Good work. . . .

He patted a wet hand on the gray's withers as they pushed on.

Moments later at a narrow fork in the trail, he spotted a thin glow of firelight perched on the hillside above him.

“Thank God,” he said in relief. He reined the gray and pulled the string of fillies sidelong onto the upward fork.

During brief intervals between twists of lightning, his only guide through the pitch-darkness came from the sound of rain splattering on the rocky trail in front of him. Three feet to his left the trickle and splatter of rain against rock fell away silent. So did the trail itself. The caldera valley lay swaddled in a black void over three feet below.

Summers had no idea what awaited him around the firelight above him, but whatever situation awaited him could be no more perilous than this trail he was on. Or so he told himself, pushing on blindly in absolute darkness, water spilling from the brim of his hat.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

Another hour had passed before Summers had worked his way up the rocky trail through the storm and the darkness. High up where the slim trail ended, he stopped and stepped down from his saddle at the entrance to an abandoned mining project. Following the glow of firelight that had drawn him like a moth, he led the horses out of the rain and under a stone overhang trussed up by thick pine timbers. Wet rifle in hand, he tied the five animals to an iron ring bolted to one of the timbers and stood in silence for a moment listening toward the flicker of fire along a descending stone wall.

Hearing no sound from within the hillside, he ventured forward into the mouth of the shaft.

“Hello the fire,” he called out. He waited, and when no reply come back to him through the flickering light along the stone walls, he called out again. Still no reply. “Coming in,” he called out.

He looked back at the shadowy horses standing in the dim, sparse light. Then he walked forward, his rifle lowered but held ready in his hand.

Twenty feet into the cavern he heard a horse nickering quietly toward him, the animal catching the scent of an encroaching stranger.

“Hello the campfire,” Summers called out again. But he did not stop and wait for a reply. He walked on as the flicker of firelight grew stronger. He stopped again when he came to a place where the shaft opened wide and smoke from a campfire swirled upward into a high broken ceiling. A smell of cooking meat wafted in the darkness. A small tin cooking pot sat off the flames on the edge of the fire. A spoon handle stuck up from it. Having not eaten all day caused Summers' belly to whine at the scent of food.

Looking all around, he heard the chuff of the horse and saw the animal standing shadowily among rocks on the far side of the campfire. Then he swung his rifle quickly at the sound of a man coughing in the darkness to his right. The cough turned into a dark, raspy chuckle as Summers saw two dark eyes glint in the flickering fire.

“Bienvenue

. . .

mon ami

,

”

a weak, gravelly voice said in French from the dark corner outside the firelight. Then the voice turned into English. “Do you bring . . . a rope for me?”

Summers heard pain in the voice. He stepped closer.

“I'm not carrying a rope,” he said, already getting an idea what was going on here. “I saw your fire. I came in out of the rain.”

“Ah . . .” The voice trailed.

Summers waited for more. When nothing came, he stepped in close enough to look down at the drawn, bearded face. “Are you hurt?”

“I am dying, thank you . . . ,” the voice said wryly, ending in a deep, harsh cough.

Summers looked around at the fireside and saw a blackened torch lying on a rock. He stepped away from the man, picked up the torch and stuck the end of it in the flames, lighting it. Then he stepped back over and held the light out over the man lying on a bloody blanket on the stone floor. The man clutched a hand to a blood-soaked bandage on his chest.

“Are you shot?” Summers asked.

“

Oui

. . . I am shot to death,” the man said with finality. He stared up at Summers. “Are you not with

them

?” He gave a weak gesture toward the world outside the stone cavern walls.

“Them . . . ?” said Summers. “I'm here on my own.”

“The man with the bay horses?” the man asked.

Summers gave him a curious look.

“We saw you . . . ,” the man said.

We . . . ?

Summers looked around again into the darkness beyond the circling firelight. Nothing.

“Yes, that was me,” he said. “Is somebody hunting you, mister?”

The wounded man shook his head slowly.

“Never mind,” the man said. He seemed stronger; he tried to prop himself up onto his elbows, but his strength failed him.

“Why don't you lie still?” said Summers, stooping down beside him.

“Water . . . food,” the man said weakly. “There is liver stew. . . .” He collapsed onto the blanket; he cut his eyes toward the fire, where a canteen stood on the stone floor.

“I'll get it for you,” Summers said.

He laid the torch on the floor, went to the fire, rifle in hand, and brought back the small tin pot and the canteen. The smell of the hot food tempted him. But he set the pot on the floor by the blanket and uncapped the canteen. He helped the man up onto his elbows and steadied the canteen while he drank. When he lowered the canteen, he capped it, laid it aside and picked up the small tin pot.

“This will get your strength up,” he said, stirring the spoon in a thickened meaty broth. He held out a spoonful, but at the last second the man turned his face away and eased himself back down on the blanket.

“You eat it,

mon ami

. I will need . . . no strength in hell . . . ,” the man sighed, and clutched his chest tighter.

Summers wasn't going to argue.

“Obliged,” he said, even as he spooned the warm, rich stew into his mouth. “Who shot you?”

“It does . . . not matter,” the man said. He paused, looked Summers up and down, then said, “What are you doing . . . in this Mexican hellhole,

mon ami

?”

“Delivering the four bay fillies you saw me leading,” Summers said. He spooned up more liver stew; he chewed and swallowed hungrily. “Taking them to a man named Ansil Swann.” He spooned up more stew, held it, then stopped. “Are you sure you don't want some of this?” he asked, just to be polite.

The man shook his head. He looked away toward the darkness and gave a dark chuckle.

“What a small and peculiar world . . . I have lived in,” he said, as if reflecting on a life that would soon leave him. He chuckled again and stifled a cough. “I know this man Swann.”

“You do?” said Summers.

“Oh yes, I know him . . . very well,” said the dying man. “It is his

viande de cheval

. . . you are eating.”

“His what?” Summers asked. He looked down the pot in his hand.

“Viande de cheval,”

the man said.

“Speak English, mister,” Summers said, getting a bad feeling about the conversation.

“Horse meat . . . ,” the man said in a laughing, rasping cough.

“Horse meat . . . ?” Summers said, staring at the rich meaty broth in the pot.

“Yes, my friend . . . ,” said the chuckling, dying man. “You are eating Ansil Swann's . . . prize racing stallion.”