Shadowfell

Authors: Juliet Marillier

The people of Alban are afraid.

The tyrannical king and his masked Enforcers are scouring the land, burning villages and enslaving the canny.

Fifteen-year-old Neryn has fled her home in the wake of their destruction, and is alone and penniless, hiding her extraordinary magical power. She can rely on no one – not even the elusive Good Folk who challenge and bewilder her with their words.

When an enigmatic stranger saves her life, Neryn and the man called Flint begin an uneasy journey together. She wants to trust Flint but how can she tell who is true in this land of evil?

For Neryn has heard whisper of a mysterious place far away: a place where rebels are amassing to free the land and end the king’s reign.

A place called Shadowfell.

An engrossing story of courage, hope, danger and love from one of the most compelling fantasy storytellers.

CONTENTS

Cover

Blurb

Dedication

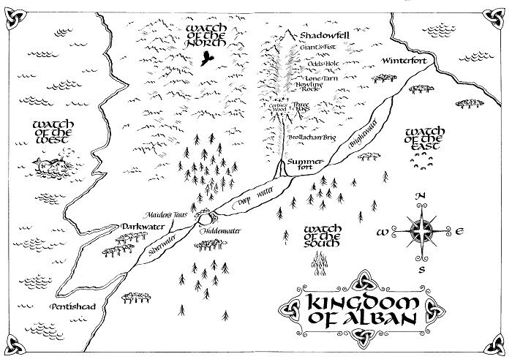

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

About the Author

Also by Juliet Marillier

Copyright page

To my grandson, Angus

CHAPTER ONE

A

S WE CAME DOWN

to the shore of Darkwater, the wind sliced cold right to my bones. My heels stung with blisters. Dusk was falling, and my head was muzzy from the weariness of another long day’s walk. Birds cried out overhead, winging to night-time roosts. They were as eager as I was to get out of the chill.

We’d heard there was a settlement not far along the loch shore, a place where we might perhaps buy shelter with our fast-shrinking store of coppers. I allowed myself to imagine a bed, a proper one with a straw mattress and a woollen coverlet. Oh, how my limbs ached for warmth and comfort! Foolish hope. The way things were in Alban, people didn’t open their doors to strangers. Especially not to dishevelled vagrants, and that was what we had become. I was a fool to believe, even for a moment, that our money would buy us time by someone’s hearth fire and a real bed. Never mind that. A heap of old sacks in a net-mending shed or a pile of straw in an outhouse would do fine. Any place out of this wind. Any place out of sight.

I became aware of silence. Father’s endless mumbled recounting of past sorrows, a constant accompaniment to our day’s journey, had come to a halt, and now he stopped walking to gaze ahead. Between the water’s edge and the looming darkness of a steep wooded hillside I could make out a cluster of dim lights.

‘Darkwater settlement,’ he said. ‘There are lights down by the jetty. The boat’s there!’

‘What boat?’ I was slow to understand, my mind dreaming of a fire, a bowl of porridge, a blanket. I did not hear the note in his voice, the one that meant trouble.

‘Fowler’s boat. The chancy-boat, Neryn. What have we got left, how much?’

My heart plummeted. When this mood took him, setting the glitter of impossible hope in his eyes, there was no stopping him. I could not restrain him by force; he was too strong for me. And whatever I said, he would ignore it. But I had to try.

‘Enough for two nights’ shelter and maybe a crust if we’re lucky, Father. There’s nothing to spare. Nothing until one of us gets some paid work, and you know how likely that is.’

‘Give me the bag.’

‘Father, no! These coppers are our safe place to sleep. They’re our shelter from the wind. Don’t you remember what happened last –’

‘Don’t tell me what to do, daughter.’ His eyes narrowed in a way that was all too familiar. ‘What’s better than a drink of ale to warm us up? Besides, I’ll double our coppers on the boat. Triple them. Nobody beats me in a game of chance. Would you doubt your father, girl?’

Doubt was hardly the word for what I felt. Yes, he had once been skilled in such games. He’d had a reputation as a tricky player, full of surprises. Sorrow and reversal, hardship and humiliation had eaten up that clever fellow, leaving a pathetic shell, a man who liked his ale too much and could no longer distinguish between reality and wild dream. Father was a danger to himself. And he was a danger to me, for strong drink loosened his tongue, and a word out of place could reveal the gift I fought to hide from the world every moment of every day. He’d talk, and someone would tell the Enforcers, and it would all be over for the two of us. But I was heartsick and weary; too weary to fight him any longer.

‘Here,’ I said, handing over the bag. ‘I hate the chancy-boat. The only chance it will give you tonight is the chance to squander what little we have. If you lose this money we’ll be sleeping out in the open, at the mercy of whoever happens to pass by. If you lose it you’ll lose what little self-respect you have left. But you’re my father, and I can’t make your choices for you.’

He looked at me directly, just for a moment, and I thought I saw a glimmer of understanding in his eyes, but it was gone as quickly as it had appeared. ‘You hate me,’ he muttered. ‘You despise your own father.’

I could have told him the truth: that I hated his weakness, that I hated his anger, that the days and months and years of looking after him and keeping him out of trouble and protecting him from himself had worn me down. But I loved him, too. He was my father. I loved the man he used to be, and I still hadn’t given up hope that, some day, he could be that man again. ‘No, Father,’ I said, plodding after him as he strode ahead, for the prospect of a game and a win had put new life in his steps. ‘I’m cold and tired, that’s all. Too tired to mind my words.’

As we made our way closer to the lights of the chancy-boat, which rocked gently in the dark water beside a small jetty, I was aware of pale eyes watching me from the branches of the pines. I did not allow myself a glance toward them. Small feet shuffled in the fallen leaves and pattered along behind us a way, then skipped off into the woods. I did not allow myself to turn back. A whisper teased at me:

Neryn! Neryn, we are here!

I closed my ears to it. I had been hiding my secret for years, since Grandmother had explained the peril of canny gifts. I had become adept at concealment.

I stiffened my spine and gritted my teeth. Maybe there would be nobody on the chancy-boat but its captain, Fowler, who had some understanding of my father’s situation. Who would want to spend such a chilly night playing games anyway? Who would be visiting such an out-of-the-way place as Darkwater? We had come here because the settlement lay so far from well-travelled roads. We had come because nobody knew us in these parts. Except Fowler, and we had not expected him. But Fowler wouldn’t talk. He was a bird of passage, a loner.

Before we set foot on the jetty, I knew the chancy-boat held a crowd. Their voices came to us through the stillness of the night, discordant and out of place under the dark, silent sky. Nobody was about in the settlement, though here and there shutters stood half-open, revealing the glow of lamps within the modest houses. The rising moon threw dancing light on the waters of the loch, as if to show us the way on board the fishing vessel that housed Fowler’s place of entertainment. The chancy-boat went from loch to loch, from bay to bay, never two nights at one mooring. They said Fowler had been a peerless warrior in the old time, the time before King Keldec. I’d heard tell that he had fought in far eastern realms, where the sun shone so hot the land was all dust, and the wind made eldritch creatures out of heat and sand. To be a warrior in Alban now was to be an agent of Keldec’s will. It was no calling for a man of conscience.

I felt a strong desire to stay in the settlement, to crouch beside a wall or in the lee of a cottage and wait for it all to be over. The prospect of an evening on a boat full of drunken, combative men made me shrink into myself. But I couldn’t leave Father on his own. There was nobody else to stop him from drinking too much, from speaking when he should be silent, from wasting our last coppers in a futile attempt to win back the pride he had lost years ago. So I followed him along the jetty, over the creaking plank and into the crowded cabin of the boat.

The place stank of sweat and ale. The moment I stepped through the door I could feel men’s eyes on me, assessing me, wondering why my father had brought me here and what advantage could be taken from the situation. I stayed just inside the entry, trying to make myself invisible, while Father greeted Fowler with a too-hearty clap on the shoulder. Within moments he was seated at the gaming table with a brimming cup of ale before him. The drink was cheap – ale made men take risks they might avoid when their heads were clear. A copper changed hands.

Let him not squander all of it

, I prayed.

Let him not lose too soon. Let him not get angry. Let him not weep

.