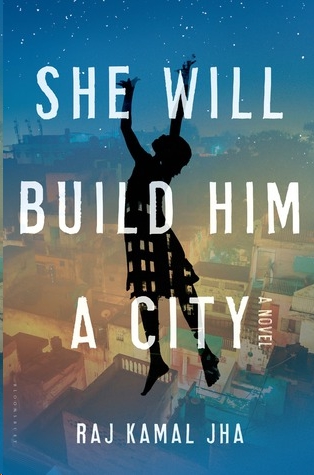

She Will Build Him a City

Read She Will Build Him a City Online

Authors: Raj Kamal Jha

To Rain,

his mother, his grandparents

&

Max Schneid (1898–1944)

Yasmin Malek (1996–2002)

Midnight had come upon the crowded city. The palace, the night-cellar, the jail, the Madhouse: the chambers of birth and death, of health and sickness, the rigid face of the corpse and the calm sleep of the child: midnight was upon them all.

Oliver Twist

Charles Dickens

, 1837

Contents

MEANWHILE: Babies Walk Through Doors Made of Glass

MEANWHILE: Two Lovers On-Board the Night Metro

MEANWHILE: The Magnificent Cockroach in the Swimming Pool

MEANWHILE: Mr Sharma’s Son and the Camera Phone

MEANWHILE: An Evening in the Life of Kalyani’s Sister

MEANWHILE: Mrs Usha Chopra Babysits in Mumbai

MEANWHILE: Reporter from Little House at Her Child

’

s Nursery School

MEANWHILE: A Day in the Life of Kalyani’s Mother

MEANWHILE: A Day in the Life of Kalyani’s Brother

MEANWHILE: Where Was Red Balloon Before Balloon Girl?

MEANWHILE: At the Protest Not Far from the AIIMS Mortuary

MEANWHILE: Hulking Black Mitsubishi Pajero at the Leela

MEANWHILE: A Gift For Apartment Complex Security Guard

Winter Afternoon

This, tonight, is a summer night, hot, gathering dark, and that is a winter afternoon, cold, falling light, when you are eight years nine years old, when you come running to me, jumping commas skipping breath, and you say, Ma, may I ask you something may I ask you something and I say, of course, baby, you may ask me anything and you say, Ma, when I am tired, when my legs hurt, when my eyes begin to close, I only need to call you, I only need to say, Ma, and you appear instantly, like magic, from wherever you are you set aside whatever you’re doing you come running to me you lift me up you carry me you walk with me you.

Slow down, slow down, I tell you, but, of course, you don’t, you say if it’s sleep time, you place pillows on either side of me, you fluff them up, you switch off the light, you wait outside my room and only when you don’t hear me move do you walk away, Ma, my question is.

And you pause.

You breathe in, deep.

You toe-tap the floor, the earth spins underneath, your eyes look into mine as if you are the mother and I am the child and you ask:

Ma, is there someone who can do the same with you?

What do you mean? I ask.

Ma, is there someone you can call when you are tired? Someone who can lift you up, carry you around until you fall asleep?

Is there someone like that, Ma? A man?

A woman?

Is there?

Is there? So many questions.

So many question marks, their dots and their hooks float in the air, block my view of your beautiful face.

And I say, yes, maybe there is.

~

Tonight is thirty years forty years later.

So quiet is this little house that I can hear, from upstairs, through the walls of the room in which you are lying, the drop of your tear, the rush of your breath.

One’s like rain, the other wind, they both make me shiver.

~

And I say yes that summer afternoon, yes, maybe there is. Maybe there is a man or a woman who can lift me up although I will be much more comfortable if it is a woman because the only man I will let myself be carried by is your father and he is no longer with us and when I say this, a little cloud, cold and wet and dark, slips in through the window, hovers over our shadows on the floor before we both blow it back into the sky where it must have come from and when we do that, I feel your breath and I remember that it is warmer than mine.

The cloud gone, you ask, Ma, doesn’t the woman who will carry you, just like you carry me, have to be tall? Very, very tall? More than twice your height? Like you are more than twice mine so that when she lifts you up, carries you around, your feet don’t drag along the floor?

I guess so, I say.

How tall should she then be, Ma? you ask.

You tell me, baby.

You think for ten seconds, twenty thirty, your lips move, numbers small and big dance inside your head – multiplying? dividing? – and you say, at least 12 feet tall, a giant, like in

Gulliver’s Travels

, Ma, in the land that comes after Lilliput, in which the little girl, nine years old, just like me, carries him like he were her doll. And to show what you mean, you raise both your arms, you stand on your toes, just over 3 feet in your socks, you try to stretch to 12, and you ask, Ma, how do we go looking for her?

Don’t you worry, I say, we will meet her. Some day some night, I am sure, because how can you keep someone so tall hidden for so long?

Ma, if she is there, will she love you like you love me?

I don’t know about that, baby, I say, maybe she will if you want her to.

Ma, will she have a mother and a father? Brothers and sisters? Friends? Will she live in a very tall house with many, many tall people?

Maybe, I say, but maybe she lives all by herself.

Let me know when you meet her, Ma, promise me that you will let me know, I want to see her carry you, I want to see you fall asleep on her shoulder.

Of course, I will, I say. Promise.

And, thus assured, you run away, leaving a hole in the air, shimmering, through which afternoon leaks away and evening drips in, mixes, dissolves the scents you leave behind.

Of winter cream and red wool.

Girl skin and baby shampoo, one night old.

~

Last night, I meet this woman.

This very, very tall woman. In this house, right here, where I stand, and, just as I promise you, I am now letting you know.

~

Have you fallen asleep?

May I lie down by your side, just for a while?

I won’t wake you up, I will walk up the stairs on tiptoe, I will wipe all my sweat away so that not one drop falls, makes a noise.

If it helps, I will whisper each word I need to tell you, I will hold my breath – as if I am dead.

Night Metro

He is going to kill and he is going to die.

That’s all we know for now, let’s see what happens in between.

~

He waits to board the last train at Rajiv Chowk Station, the central hub of the Delhi Metro, crossover for Yellow and Blue Lines, through which move half-a-million passengers each day of whom he is one.

Nobody in this city notices one.

He is thirty years, thirty-five years old, 5

'

10

''

, 5

'

11

''

, his wrist so slim his watch slides halfway to his elbow when he raises his arm to brush back his hair. It’s over 40 degrees but there’s not a single bead of sweat on his face as if an invisible layer of ice-cold air sticks to him like cling film. Both hands free, he holds no bag, no phone as he waits at the platform, two levels below the street, next to Café Coffee Day under the Metro Clock whose hand shudders each time it moves a second.