Shine Shine Shine (14 page)

Authors: Lydia Netzer

In school, she would reference Bob Butcher in passing, and call him “My father who died” or “My father who was killed by Communists” or “My dead father.” There were other children in her middle school whose fathers were gone. There was one other child whose father was dead, of a heart attack, at age forty-five. That poor kid, having stood over his father’s grave, and cried with real tears and snot, was not able to translate this experience into any sort of social status, because he was always coming in with a little dairy farm on his brown shoes, and it didn’t matter to the other kids, whatever thing was festering in him. He could visit his father’s grave, and no one put their arm around him. But there was a lot of curiosity, about Sunny’s family in general, coming from the community. So eventually Sunny was asked, by one of the girls from Foxburg whose families still had money, to tell everyone exactly how her father died, anyway. “What’s the deal with your dad,” said this girl to Sunny. “How did he die anyway?”

Sunny, her social instinct strong even at the age of eleven, was able to deflect. Rather than giving up her mystery in the moment, she was wise enough to say, “Yes, I will tell you, but not today.” She chewed her gum cryptically, rolled her eyes, slammed her locker shut. Then she delivered a brilliant smile, and pushed off down the hall.

“I will tell you,” said Sunny when pressed again by this other local rich girl with a very severe ponytail and curls. “Next week at some point, probably, down by the track. During track practice. Meet me.”

Sunny never did any sports in middle school or high school, but she did watch the track team practice, dutifully, most every day. She had a crush on one of the boys. There were kids coming over, like they always did, waiting for their mothers to pick them up, or skipping out on play practice, or pep band or whatever. But now they would sit there near to Sunny, where she was perched up on the bleachers, watching the distance runners loping around. They looked expectantly at her, but she didn’t have much to say on the matter. Around the middle of the week, someone said, “Well, are you going to tell us pretty soon?” And Sunny said, abruptly, that this would be the day she would tell. She slammed her math notebook shut and put it aside, chewed her pencil absently, then threw it over her shoulder.

“My father died,” she said, “on a plateau. He was high up in Tibet.” The warm breeze blew across the green valley, up from the river. The track was nestled in a little dell, down behind the school. In this land of rolling hills, there was hardly an acre of level ground in the entire county, making swimming pools almost an impossibility. The children around her turned their faces toward her, their skeletons obscured by the shape of their hair. A couple were wearing hats, too. Their butts made the wooden bleachers creak, the chipped green paint getting into the seams of their jeans. “That’s near China,” she added. “Outside.” One of the kids nodded. One of the kids looked at another kid and quietly muttered, “No, it’s not.” The track kids pounded past, another lap of the asphalt counted. Sunny cleared her throat.

“It was winter in Tibet,” she went on, “and the Communists had guns.” Now the kids sat up a bit more and paid attention. Sunny clasped her hands together and turned them inside out, stretching out her elbows. She yawned.

“How many Communists were there?” asked one girl.

“Three,” said Sunny. “There were three Communists, in brown military uniforms. The uniforms of the Chinese Liberation Army of the People’s Democracy. They were supposed to be exterminating all the missionaries, even the ones who had families to support. My father had left us to escape the Communists. He had been hiding in a Buddhist monastery, but when the Communists came to the monastery, they found him there. He was in a dark room, between two clay jars of water. Probably praying or something. They came into the room, and tipped the jars over one by one onto the floor. The clay lids were breaking, water spilling everywhere, all over the place. My father stood up, in the middle of all this breaking pottery and monastery stuff, and said, ‘I’m here.’ And they dragged him out, up the mountain and onto a high flat rock. There were monks, um, dying all around. Getting bayoneted.”

“But what did he do?” asked a boy in red shorts. “Why was he in trouble?”

“For not being a Communist, obviously,” said Sunny kindly, and the other kids looked at this red-shorts kid like he was a complete idiot.

“So they dragged him up there on this high rock, one on each side and one marching behind. That was uncomfortable. And they threw him down on a flat place on the ground. ‘Do you believe in communism?’ they said to him. ‘No,’ said my father. ‘I will never believe in communism!’”

Sunny’s voice echoed across the track. She put up a bony fist and shook it. “They kicked him in the stomach, and began to walk around him in a circle, kicking him. ‘Do you believe in communism?’ they kept saying, but he would always say ‘No!’ and then they would kick him again. Their boots were dry and hard, and they had short legs. But there was no dust around, there’s no dust in Tibet because there is no dirt, only rock. These soldiers, their faces were flat and Chinesey, but really tough and mean. Finally they turned toward him, pointing all their guns right at his head, and they pulled him up so he was kneeling on the rock, and then they shot him. Dead.”

“Holy crap,” said one boy, impressed. A horn honked in the parking lot, as somebody’s mother had arrived. The track team had separated out now, a long trail dripping back from the lead group. At the front of the pack, Sunny watched a long, lean boy with a shaved head run mechanically past. Others followed, breathing hard, marking out another mile.

“In Tibet you can’t bury people,” Sunny went on. “You can’t dig; the rock is too hard. So they chopped him up into pieces with these big steel machetes, and left him there, for the vultures. They didn’t talk while they were doing it, they just kind of chop, chop, chopped. The rock turned all bloody with his blood, making red pools here and there on the rock. And then they went off down the mountain. After the vultures had eaten him, his bones dried, and eventually they blew off that rock, and became just part of the gravel. White bones.”

“How could you even know that,” said the cynic in red shorts.

“Shut up, man!” said the kid next to him, and pushed him off the bleachers.

“Sunny, that’s horrible,” said the girl with the curly ponytail. “You must feel so bad.”

Sunny nodded and watched the runners. She laced her fingers over the scarf behind her neck. Her eyes were wet.

* * *

S

UNNY TOLD THE STORY

again in college. She wrote a poem about it for an elective poetry workshop she was taking. In this version of the story, her father hung from his heels from a bar on a wall in a Burmese prison.

Only his shoulders and head rested on the ground. He hung there until he died, and only her mother was able to approach him, and then only from the other side of iron bars. The cell was dark and moldy. The prisoner wore no clothes. The agony, she wrote in her poem, was only increased by mosquitoes. The filth, she informed her readers, was only relieved by death. For crimes against the government, for subversive activity, for endangering the republic, and for Christianity, her father was hung up to rot.

Her mother walked all the way from Mandalay to Rangoon, heavy in pregnancy, and delivered her baby in the dark, in a thicket behind the ruined palace. She tucked the baby into her own lungi, cleaned herself up, and that very night she went to visit her husband. She was shown to his cell, where he was kept alone at the end of a long low building. In the doorway, she called to him. She pushed the baby in between the bars, to show the father what he had made. A crow sat silently in the window. A snake slipped down the wall. The baby cried and writhed there in the dark, and the father turned his tortured head and cracked his lips into a smile, seeing her.

That baby,

said Sunny while the class was discussing her work,

was me. That baby was me.

She left out the eclipse in this version of her story. She thought it would sound too unrealistic.

The poem was published in the college’s literary magazine, the student editors invited Sunny to read it in a little chapel on campus. At the end of her reading of the poem, there was silence in the chapel, and then applause.

* * *

W

HEN

S

UNNY AND

M

AXON

moved to Virginia, Sunny threw a housewarming party for herself. She invited everyone on their street, and everyone came. She had enough martini glasses for everyone. The house was perfect, like a spread in

Architectural Digest

. Pistachio cream rugs, a wide walnut plank floor, brushed-nickel cups for the recessed lights, and a golden ficus, glossy curved leaves like a money tree in the corner. Everything was new, down to the distressed-leather buster chair and ottoman, but it looked a hundred years old, like a house in which life-altering decisions had been made, a house that had been left and returned to, from faraway travels. A house in which treaties had been signed. A genuine house.

They had disposed of their old coffee table, a huge chunk of green glass. It wasn’t child safe at all, but that was the least of its issues. “It doesn’t look right,” she said to Maxon. “And to be frank, baby, neither do you.” Maxon, like the great green coffee table, would not have been featured in

Architectural Digest

. Sunny didn’t want to sell it, so she rolled it out into the alleyway and left it, like a translucent question mark in the city.

She would never have rolled Maxon out into an alleyway. However, if she had been able to confine Maxon to his study on that night, she would have closed the big heavy door on him, and stuck duct tape around the seams of it, so that not even the slightest bit of air or hint of Maxon would come out.

It’s not like he had even wanted to come. It’s not like he had said, “Can I come?” In fact he had said very clearly, “I do not feel comfortable with anyone coming into this house. It appears you have invited the whole neighborhood.”

“Maxon, the more the merrier,” Sunny had trilled, smiling down into the sink, washing carrots.

“That’s a terrible phrase,” he had said. He grabbed a diet Coke from the fridge.

“But really, it’s socially accurate,” said Sunny, “and in this case the numbers are in your favor.”

“How’s that,” he said, snapping open the can. She gesticulated with a shaved carrot, a twinkle in her eye.

“The more people, the less you have to talk, actually, right? If I invited one person over, you’d have to talk plenty. But with twenty people here, you can disappear into the sofa. Nod, smile, and no one will notice.”

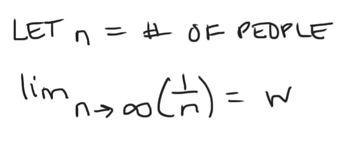

Maxon swept the magnets off the fridge, the recycling calendar, the postcards, and attacked it with his dry-erase marker. He always had one somewhere. She loved to watch him work, loved to see him put it into his own language. In a moment like this, when everything went flying, she knew they were really communicating.

“So, like this?” he said.

“And

w

is the number of words I’m responsible for?” He paused, waiting, his marker still hovering over his last equation.

“Yeah, I mean it can go up to fifty percent if

n

equals two. You know, like a dinner date. But if

n

equals twenty, negligible.”

“Great,” he said. “Well, okay. I see your point. But for the moment I’m going back to my office, where

n

equals one.”

“Maxon, where

n

equals one there should be no talking!”

She let him go. But she had to allow him to come out if he wanted to come. They knew who he was. Maybe they would put his behavior in context. As the hour arrived, she put the finishing touches on her own wig, asked the maid to pay special attention to the baseboards, and hoped after all that Maxon would not emerge. Maybe if the house looked magnificent enough, they would not notice his absence.

The favorite final touch, she thought, was a glass cabinet that held their curios: a Burmese nat, a basket of pinecones from the woods by her mother’s house, and on the top shelf a ten-thousand-dollar Mont Blanc pen. The pen had never been used, so it sat there in a spotlight, completely full of ink. She had found it in a catalog full of other such things, pens so expensive they must be kept in cabinets, wallets made of lambskin, all the things that real people use, responsible parents, not weirdos who wandered in from another planet or continent and decided to have kids. Sunny looked on it with love, as if it were her real husband, this pen, so perfectly made and elegantly wrought. Hello, she would say to her guests. I’m Sunny Mann, and this is my husband, Maxon. She would point to the pen. All of the guests would incline their heads toward the pen and nod and smile. The pen would glisten perfectly. It would not say anything strange or crack its thumbs loudly.

Sunny was pregnant, just getting used to the feeling of a wig on her head, and just getting used to the feeling of another person moving around inside her, nourished from her bloodstream, holding its breath, waiting to emerge. She was really trying to make everything all right for the baby to come out. She was really trying to correct the wrongs that had been established in the universe, all of the missing fathers and the baldness and the condition people kindly called “eccentricity” now that Maxon was a millionaire.